One Dimensional Monte Carlo Integration

Our Buffon Needle example is a way of calculating $\pi$ by solving for the ratio of the area of the circle and the area of the inscribing square:

$$ \frac{\operatorname{area}(\mathit{circle})}{\operatorname{area}(\mathit{square})}

= \frac{\pi}{4}

$$

We picked a bunch of random points in the inscribing square and counted the fraction of them that were also in the unit circle. This fraction was an estimate that tended toward $\frac{\pi}{4}$ as more points were added. If we didn't know the area of a circle, we could still solve for it using the above ratio. We know that the ratio of areas of the unit circle and the inscribing square is $\frac{\pi}{4}$, and we know that the area of a inscribing square is $4r^2$, so we could then use those two quantities to get the area of a circle:

$$ \frac{\operatorname{area}(\mathit{circle})}{\operatorname{area}(\mathit{square})}

= \frac{\pi}{4}

$$

$$ \frac{\operatorname{area}(\mathit{circle})}{(2r)^2} = \frac{\pi}{4} $$

$$ \operatorname{area}(\mathit{circle}) = \frac{\pi}{4} 4r^2 $$

$$ \operatorname{area}(\mathit{circle}) = \pi r^2 $$

We choose a circle with radius $r = 1$ and get:

$$ \operatorname{area}(\mathit{circle}) = \pi $$

Our work above is equally valid as a means to solve for $pi$ as it is a means to solve for the area of a circle:

#include "rtweekend.h"

#include <iostream>

#include <iomanip>

#include <math.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main() {

int N = 100000;

int inside_circle = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

auto x = random_double(-1,1);

auto y = random_double(-1,1);

if (x*x + y*y < 1)

inside_circle++;

}

std::cout << std::fixed << std::setprecision(12);

std::cout << "Estimated area of unit circle = " << (4.0 * inside_circle) / N << '\n';

}

Expected Value

Let's take a step back and think about our Monte Carlo algorithm a little bit more generally.

If we assume that we have all of the following:

-

A list of values $X$ that contains members $x_i$:

$$ X = (x_0, x_1, ..., x_{N-1}) $$

-

A continuous function $f(x)$ that takes members from the list:

$$ y_i = f(x_i) $$

-

A function $F(X)$ that takes the list $X$ as input and produces the list $Y$ as output:

$$ Y = F(X) $$

-

Where output list $Y$ has members $y_i$:

$$ Y = (y_0, y_1, ..., y_{N-1}) = (f(x_0), f(x_1), ..., f(x_{N-1})) $$

If we assume all of the above, then we could solve for the arithmetic mean--the average--of the list $Y$ with the following:

$$ \operatorname{average}(Y) = E[Y] = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=0}^{N-1} y_i $$

$$ = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=0}^{N-1} f(x_i) $$

$$ = E[F(X)] $$

Where $E[Y]$ is referred to as the expected value of $Y$. If the values of $x_i$ are chosen randomly from a continuous interval $[a,b]$ such that $ a \leq x_i \leq b $ for all values of $i$, then $E[F(X)]$ will approximate the average of the continuous function $f(x')$ over the the same interval $ a \leq x' \leq b $.

$$ E[f(x') | a \leq x' \leq b] \approx E[F(X) | X =

\{\small x_i | a \leq x_i \leq b \normalsize \} ] $$

$$ \approx E[Y = \{\small y_i = f(x_i) | a \leq x_i \leq b \normalsize \} ] $$

$$ \approx \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=0}^{N-1} f(x_i) $$

If we take the number of samples $N$ and take the limit as $N$ goes to $\infty$, then we get the following:

$$ E[f(x') | a \leq x' \leq b] = \lim_{N \to \infty} \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=0}^{N-1} f(x_i) $$

Within the continuous interval $[a,b]$, the expected value of continuous function $f(x')$ can be perfectly represented by summing an infinite number of random points within the interval. As this number of points approaches $\infty$ the average of the outputs tends to the exact answer. This is a Monte Carlo algorithm.

Sampling random points isn't our only way to solve for the expected value over an interval. We can also choose where we place our sampling points. If we had $N$ samples over an interval $[a,b]$ then we could choose to equally space points throughout:

$$ x_i = a + i \Delta x $$

$$ \Delta x = \frac{b - a}{N} $$

Then solving for their expected value:

$$ E[f(x') | a \leq x' \leq b] \approx \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=0}^{N-1} f(x_i)

\Big|_{x_i = a + i \Delta x} $$

$$ E[f(x') | a \leq x' \leq b] \approx \frac{\Delta x}{b - a} \sum_{i=0}^{N-1} f(x_i)

\Big|_{x_i = a + i \Delta x} $$

$$ E[f(x') | a \leq x' \leq b] \approx \frac{1}{b - a} \sum_{i=0}^{N-1} f(x_i) \Delta x

\Big|_{x_i = a + i \Delta x} $$

Take the limit as $N$ approaches $\infty$

$$ E[f(x') | a \leq x' \leq b] = \lim_{N \to \infty} \frac{1}{b - a} \sum_{i=0}^{N-1}

f(x_i) \Delta x \Big|_{x_i = a + i \Delta x} $$

This is, of course, just a regular integral:

$$ E[f(x') | a \leq x' \leq b] = \frac{1}{b - a} \int_{a}^{b} f(x) dx $$

If you recall your introductory calculus class, the integral of a function is the area under the curve over that interval:

$$ \operatorname{area}(f(x), a, b) = \int_{a}^{b} f(x) dx$$

Therefore, the average over an interval is intrinsically linked with the area under the curve in that interval.

$$ E[f(x) | a \leq x \leq b] = \frac{1}{b - a} \cdot \operatorname{area}(f(x), a, b) $$

Both the integral of a function and a Monte Carlo sampling of that function can be used to solve for the average over a specific interval. While integration solves for the average with the sum of infinitely many infinitesimally small slices of the interval, a Monte Carlo algorithm will approximate the same average by solving the sum of ever increasing random sample points within the interval. Counting the number of points that fall inside of an object isn't the only way to measure its average or area. Integration is also a common mathematical tool for this purpose. If a closed form exists for a problem, integration is frequently the most natural and clean way to formulate things.

I think a couple of examples will help.

Integrating x²

Let’s look at a classic integral:

$$ I = \int_{0}^{2} x^2 dx $$

We could solve this using integration:

$$ I = \frac{1}{3} x^3 \Big|_{0}^{2} $$

$$ I = \frac{1}{3} (2^3 - 0^3) $$

$$ I = \frac{8}{3} $$

Or, we could solve the integral using a Monte Carlo approach. In computer sciency notation, we might write this as:

$$ I = \operatorname{area}( x^2, 0, 2 ) $$

We could also write it as:

$$ E[f(x) | a \leq x \leq b] = \frac{1}{b - a} \cdot \operatorname{area}(f(x), a, b) $$

$$ \operatorname{average}(x^2, 0, 2) = \frac{1}{2 - 0} \cdot \operatorname{area}( x^2, 0, 2 ) $$

$$ \operatorname{average}(x^2, 0, 2) = \frac{1}{2 - 0} \cdot I $$

$$ I = 2 \cdot \operatorname{average}(x^2, 0, 2) $$

The Monte Carlo approach:

#include "rtweekend.h"

#include <iostream>

#include <iomanip>

#include <math.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main() {

int a = 0;

int b = 2;

int N = 1000000;

auto sum = 0.0;

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

auto x = random_double(a, b);

sum += x*x;

}

std::cout << std::fixed << std::setprecision(12);

std::cout << "I = " << (b - a) * (sum / N) << '\n';

}

This, as expected, produces approximately the exact answer we get with integration, i.e. $I = 8/3$. You could rightly point to this example and say that the integration is actually a lot less work than the Monte Carlo. That might be true in the case where the function is $f(x) = x^2$, but there exist many functions where it might be simpler to solve for the Monte Carlo than for the integration, like $f(x) = sin^5(x)$.

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

auto x = random_double(a, b);

sum += pow(sin(x), 5.0);

}

We could also use the Monte Carlo algorithm for functions where an analytical integration does not exist, like $f(x) = \ln(\sin(x))$.

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

auto x = random_double(a, b);

sum += log(sin(x));

}

In graphics, we often have functions that we can write down explicitly but that have a complicated

analytic integration, or, just as often, we have functions that can be evaluated but that can't

be written down explicitly, and we will frequently find ourselves with a function that can only be

evaluated probabilistically. The function ray_color from the first two books is an example of a

function that can only be determined probabilistically. We can’t know what color can be seen from

any given place in all directions, but we can statistically estimate which color can be seen from

one particular place, for a single particular direction.

Density Functions

The ray_color function that we wrote in the first two books, while elegant in its simplicity, has

a fairly major problem. Small light sources create too much noise. This is because our uniform

sampling doesn’t sample these light sources often enough. Light sources are only sampled if a ray

scatters toward them, but this can be unlikely for a small light, or a light that is far away. If

the background color is black, then the only real sources of light in the scene are from the lights

that are actually placed about the scene. There might be two rays that intersect at nearby points on

a surface, one that is randomly reflected toward the light and one that is not. The ray that is

reflected toward the light will appear a very bright color. The ray that is reflected to somewhere

else will appear a very dark color. The two intensities should really be somewhere in the middle.

We could lessen this problem if we steered both of these rays toward the light, but this would cause

the scene to be inaccurately bright.

For any given ray, we usually trace from the camera, through the scene, and terminate at a light. But imagine if we traced this same ray from the light source, through the scene, and terminated at the camera. This ray would start with a bright intensity and would lose energy with each successive bounce around the scene. It would ultimately arrive at the camera, having been dimmed and colored by its reflections off various surfaces. Now, imagine if this ray was forced to bounce toward the camera as soon as it could. It would appear inaccurately bright because it hadn't been dimmed by successive bounces. This is analogous to sending more random samples toward the light. It would go a long way toward solving our problem of having a bright pixel next to a dark pixel, but it would then just make all of our pixels bright.

We can remove this inaccuracy by downweighting those samples to adjust for the over-sampling. How do we do this adjustment? Well, we'll first need to understand the concept of a probability density function. But to understand the concept of a probability density function, we'll first need to know what a density function is.

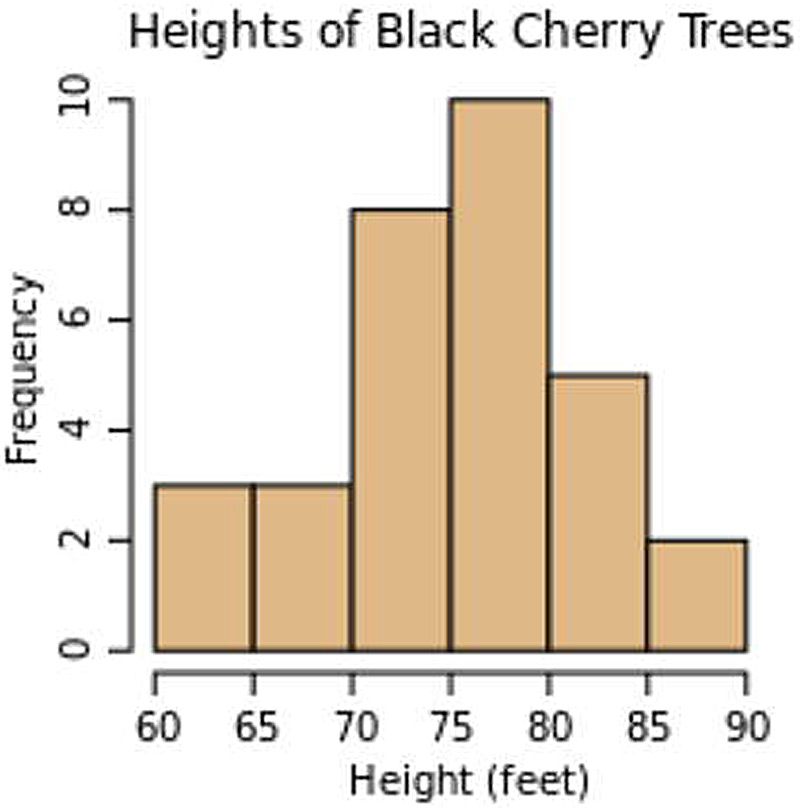

A density function is just the continuous version of a histogram. Here’s an example of a histogram from the histogram Wikipedia page:

If we had more items in our data source, the number of bins would stay the same, but each bin would have a higher frequency of each item. If we divided the data into more bins, we'd have more bins, but each bin would have a lower frequency of each item. If we took the number of bins and raised it to infinity, we'd have an infinite number of zero-frequency bins. To solve for this, we'll replace our histogram, which is a discrete function, with a discrete density function. A discrete density function differs from a discrete function in that it normalizes the y-axis to a fraction or percentage of the total, i.e its density, instead of a total count for each bin. Converting from a discrete function to a discrete density function is trivial:

$$ \text{Density of Bin i} = \frac{\text{Number of items in Bin i}}

{\text{Number of items total}} $$

Once we have a discrete density function, we can then convert it into a density function by changing our discrete values into continuous values.

$$ \text{Bin Density} = \frac{(\text{Fraction of trees between height }H\text{ and }H’)}

{(H-H’)} $$

So a density function is a continuous histogram where all of the values are normalized against a total. If we had a specific tree we wanted to know the height of, we could create a probability function that would tell us how likely it is for our tree to fall within a specific bin.

$$ \text{Probability of Bin i} = \frac{\text{Number of items in Bin i}}

{\text{Number of items total}} $$

If we combined our probability function and our (continuous) density function, we could interpret that as a statistical predictor of a tree’s height:

$$ \text{Probability a random tree is between } H \text{ and } H’ =

\text{Bin Density}\cdot(H-H’)$$

Indeed, with this continuous probability function, we can now say the likelihood that any given tree has a height that places it within any arbitrary span of multiple bins. This is a probability density function (henceforth PDF). In short, a PDF is a continuous function that can be integrated over to determine how likely a result is over an integral.

Constructing a PDF

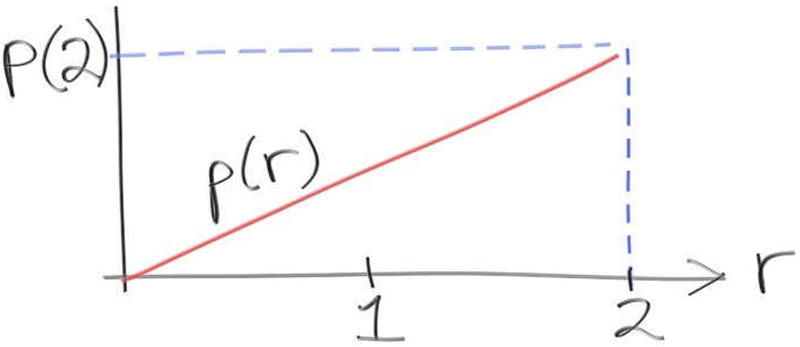

Let’s make a PDF and play around with it to build up an intuition. We'll use the following function:

What does this function do? Well, we know that a PDF is just a continuous function that defines the likelihood of an arbitrary range of values. This function $p(r)$ is constrained between $0$ and $2$ and linearly increases along that interval. So, if we used this function as a PDF to generate a random number then the probability of getting a number near zero would be less than the probability of getting a number near two.

The PDF $p(r)$ is a linear function that starts with $0$ at $r=0$ and monotonically increases to its highest point at $p(2)$ for $r=2$. What is the value of $p(2)$? What is the value of $p(r)$? Maybe $p(2)$ is 2? The PDF increases linearly from 0 to 2, so guessing that the value of $p(2)$ is 2 seems reasonable. At least it looks like it can't be 0.

Remember that the PDF is a probability function. We are constraining the PDF so that it lies in the range [0,2]. The PDF represents the continuous density function for a probabilistic list. If we know that everything in that list is contained within 0 and 2, we can say that the probability of getting a value between 0 and 2 is 100%. Therefore, the area under the curve must sum to 1:

$$ \operatorname{area}(p(r), 0, 2) = 1 $$

All linear functions can be represented as a constant term multiplied by a variable.

$$ p(r) = C \cdot r $$

We need to solve for the value of $C$. We can use integration to work backwards.

$$ 1 = \operatorname{area}(p(r), 0, 2) $$

$$ = \int_{0}^{2} C \cdot r dr $$

$$ = C \cdot \int_{0}^{2} r dr $$

$$ = C \cdot \frac{r^2}{2} \Big|_{0}^{2} $$

$$ = C ( \frac{2^2}{2} - \frac{0}{2} ) $$

$$ C = \frac{1}{2} $$

That gives us the PDF of $p(r) = r/2$. Just as with histograms we can sum up (integrate) the region to figure out the probability that $r$ is in some interval $[x_0,x_1]$:

$$ \operatorname{Probability} (r | x_0 \leq r \leq x_1 )

= \operatorname{area}(p(r), x_0, x_1)

$$

$$ \operatorname{Probability} (r | x_0 \leq r \leq x_1 ) = \int_{x_0}^{x_1} \frac{r}{2} dr $$

To confirm your understanding, you should integrate over the region $r=0$ to $r=2$, you should get a probability of 1.

After spending enough time with PDFs you might start referring to a PDF as the probability that a variable $r$ is value $x$, i.e. $p(r=x)$. Don't do this. For a continuous function, the probability that a variable is a specific value is always zero. A PDF can only tell you the probability that a variable will fall within a given interval. If the interval you're checking against is a single value, then the PDF will always return a zero probability because its "bin" is infinitely thin (has zero width). Here's a simple mathematical proof of this fact:

$$ \operatorname{Probability} (r = x) = \int_{x}^{x} p(r) dr $$

$$ = P(r) \Big|_{x}^{x} $$

$$ = P(x) - P(x) $$

$$ = 0 $$

Finding the probability of a region surrounding x may not be zero:

$$ \operatorname{Probability} (r | x - \Delta x < r < x + \Delta x ) =

\operatorname{area}(p(r), x - \Delta x, x + \Delta x) $$

$$ = P(x + \Delta x) - P(x - \Delta x) $$

Choosing our Samples

If we have a PDF for the function that we care about, then we have the probability that the function will return a value within an arbitrary interval. We can use this to determine where we should sample. Remember that this started as a quest to determine the best way to sample a scene so that we wouldn't get very bright pixels next to very dark pixels. If we have a PDF for the scene, then we can probabilistically steer our samples toward the light without making the image inaccurately bright. We already said that if we steer our samples toward the light then we will make the image inaccurately bright. We need to figure out how to steer our samples without introducing this inaccuracy, this will be explained a little bit later, but for now we'll focus on generating samples if we have a PDF. How do we generate a random number with a PDF? For that we will need some more machinery. Don’t worry -- this doesn’t go on forever!

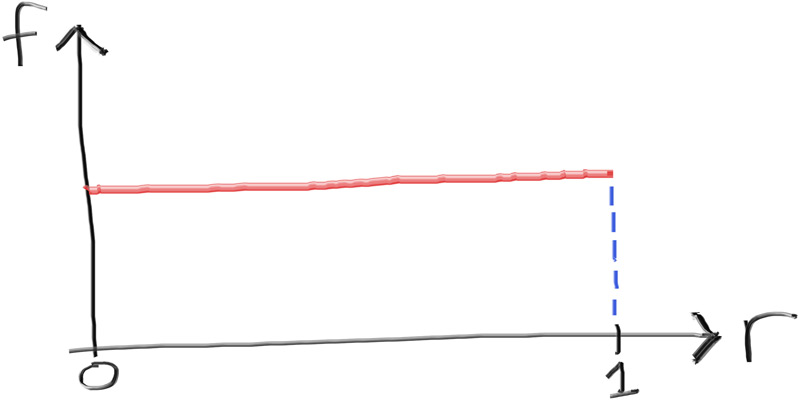

Our random number generator random_double() produces a random double between 0 and 1. The number

generator is uniform between 0 and 1, so any number between 0 and 1 has equal likelihood. If our PDF

is uniform over a domain, say $[0,10]$, then we can trivially produce perfect samples for this

uniform PDF with

That's an easy case, but the vast majority of cases that we're going to care about are nonuniform. We need to figure out a way to convert a uniform random number generator into a nonuniform random number generator, where the distribution is defined by the PDF. We'll just assume that there exists a function $f(d)$ that takes uniform input and produces a nonuniform distribution weighted by PDF. We just need to figure out a way to solve for $f(d)$.

For the PDF given above, where $p(r) = \frac{r}{2}$, the probability of a random sample is higher toward 2 than it is toward 0. There is a greater probability of getting a number between 1.8 and 2.0 than between 0.0 and 0.2. If we put aside our mathematics hat for a second and put on our computer science hat, maybe we can figure out a smart way of partitioning the PDF. We know that there is a higher probability near 2 than near 0, but what is the value that splits the probability in half? What is the value that a random number has a 50% chance of being higher than and a 50% chance of being lower than? What is the $x$ that solves:

$$ 50\% = \int_{0}^{x} \frac{r}{2} dr = \int_{x}^{2} \frac{r}{2} dr $$

Solving gives us:

$$ 0.5 = \frac{r^2}{4} \Big|_{0}^{x} $$

$$ 0.5 = \frac{x^2}{4} $$

$$ x^2 = 2$$

$$ x = \sqrt{2}$$

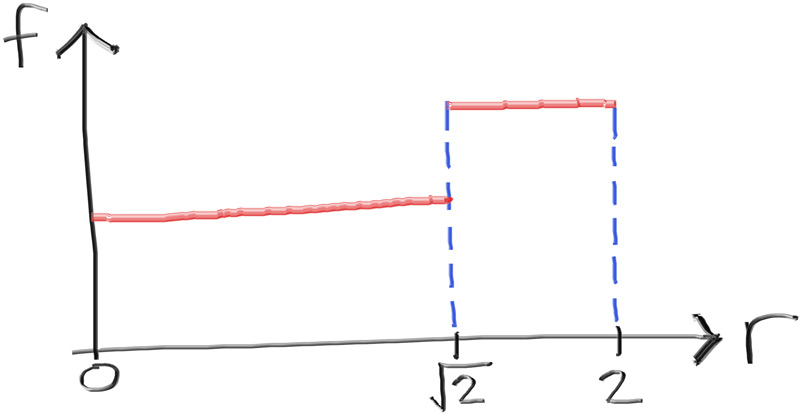

As a crude approximation we could create a function f(d) that takes as input

double d = random_double(). If d is less than (or equal to) 0.5, it produces a uniform number

in $[0,\sqrt{2}]$, if d is greater than 0.5, it produces a uniform number in $[\sqrt{2}, 2]$.

double f(double d)

{

if (d <= 0.5)

return sqrt(2.0) * random_double();

else

return sqrt(2.0) + (2 - sqrt(2.0)) * random_double();

}

While our initial random number generator was uniform from 0 to 1:

Our, new, crude approximation for $\frac{r}{2}$ is nonuniform (but only just):

We had the analytical solution to the integration above, so we could very easily solve for the 50% value. But we could also solve for this 50% value experimentally. There will be functions that we either can't or don't want to solve for the integration. In these cases, we can get an experimental result close to the real value. Let's take the function:

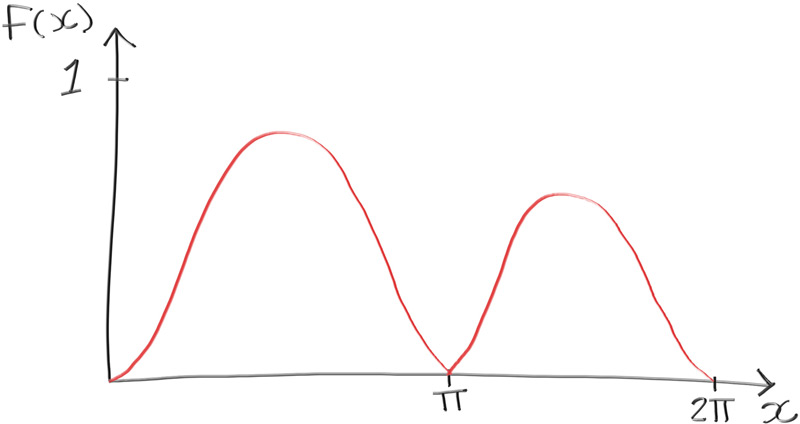

$$ p(x) = e^{\frac{-x}{2 \pi}} sin^2(x) $$

Which looks a little something like this:

At this point you should be familiar with how to experimentally solve for the area under a curve.

We'll take our existing code and modify it slightly to get an estimate for the 50% value. We want to

solve for the $x$ value that gives us half of the total area under the curve. As we go along and

solve for the rolling sum over N samples, we're also going to store each individual sample alongside

its p(x) value. After we solve for the total sum, we'll sort our samples and add them up until we

have an area that is half of the total. From $0$ to $2\pi$ for example:

#include "rtweekend.h"

#include <algorithm>

#include <vector>

#include <iostream>

#include <iomanip>

#include <math.h>

#include <cmath>

#include <stdlib.h>

struct sample {

double x;

double p_x;

};

bool compare_by_x(const sample& a, const sample& b) {

return a.x < b.x;

}

int main() {

int N = 10000;

double sum = 0.0;

// iterate through all of our samples

std::vector<sample> samples;

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

// Get the area under the curve

auto x = random_double(0, 2*pi);

auto sin_x = sin(x);

auto p_x = exp(-x / (2*pi)) * sin_x * sin_x;

sum += p_x;

// store this sample

sample this_sample = {x, p_x};

samples.push_back(this_sample);

}

// Sort the samples by x

std::sort(samples.begin(), samples.end(), compare_by_x);

// Find out the sample at which we have half of our area

double half_sum = sum / 2.0;

double halfway_point = 0.0;

double accum = 0.0;

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++){

accum += samples[i].p_x;

if (accum >= half_sum){

halfway_point = samples[i].x;

break;

}

}

std::cout << std::fixed << std::setprecision(12);

std::cout << "Average = " << sum / N << '\n';

std::cout << "Area under curve = " << 2 * pi * sum / N << '\n';

std::cout << "Halfway = " << halfway_point << '\n';

}

This code snippet isn't too different from what we had before. We're still solving for the sum over an interval (0 to $2\pi$). Only this time, we're also storing and sorting all of our samples by their input and output. We use this to determine the point at which they subtotal half of the sum across the entire interval. Once we know that our first $j$ samples sum up to half of the total sum, we know that the $j\text{th}$ $x$ roughly corresponds to our halfway point:

If you solve for the integral from $0$ to $2.016$ and from $2.016$ to $2\pi$ you should get almost exactly the same result for both.

We have a method of solving for the halfway point that splits a PDF in half. If we wanted to, we could use this to create a nested binary partition of the PDF:

- Solve for halfway point of a PDF

- Recurse into lower half, repeat step 1

- Recurse into upper half, repeat step 1

Stopping at a reasonable depth, say 6–10. As you can imagine, this could be quite computationally expensive. The computational bottleneck for the code above is probably sorting the samples. A naive sorting algorithm can have an algorithmic complexity of $\mathcal{O}(\mathbf{n^2})$ time, which is tremendously expensive. Fortunately, the sorting algorithm included in the standard library is usually much closer to $\mathcal{O}(\mathbf{n\log{}n})$ time, but this can still be quite expensive, especially for millions or billions of samples. But this will produce decent nonuniform distributions of nonuniform numbers. This divide and conquer method of producing nonuniform distributions is used somewhat commonly in practice, although there are much more efficient means of doing so than a simple binary partition. If you have an arbitrary function that you wish to use as the PDF for a distribution, you'll want to research the Metropolis-Hastings Algorithm.

Approximating Distributions

This was a lot of math and work to build up a couple of notions. Let's return to our initial PDF. For the intervals without an explicit probability, we assume the PDF to be zero. So for our example from the beginning of the chapter, $p(r) = 0$, for $r \notin [0,2]$. We can rewrite our $p(r)$ in piecewise fashion:

$$ p(r)=\begin{cases}

0 & r < 0 \\

\frac{r}{2} & 0 \leq r \leq 2 \\

0 & 2 < r \\

\end{cases}

$$

If you consider what we were trying to do in the previous section, a lot of math revolved around the accumulated area (or accumulated probability) from zero. In the case of the function

$$ f(x) = e^{\frac{-x}{2 \pi}} sin^2(x) $$

we cared about the accumulated probability from $0$ to $2\pi$ (100%) and the accumulated probability from $0$ to $2.016$ (50%). We can generalize this to an important term, the Cumulative Distribution Function $P(x)$ is defined as:

$$ P(x) = \int_{-\infty}^{x} p(x') dx' $$

Or,

$$ P(x) = \operatorname{area}(p(x'), -\infty, x) $$

Which is the amount of cumulative probability from $-\infty$. We rewrote the integral in terms of $x'$ instead of $x$ because of calculus rules, if you're not sure what it means, don't worry about it, you can just treat it like it's the same. If we take the integration outlined above, we get the piecewise $P(r)$:

$$ P(r)=\begin{cases}

0 & r < 0 \\

\frac{r^2}{4} & 0 \leq r \leq 2 \\

1 & 2 < r \\

\end{cases}

$$

The Probability Density Function (PDF) is the probability function that explains how likely an interval of numbers is to be chosen. The Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF) is the distribution function that explains how likely all numbers smaller than its input is to be chosen. To go from the PDF to the CDF, you need to integrate from $-\infty$ to $x$, but to go from the CDF to the PDF, all you need to do is take the derivative:

$$ p(x) = \frac{d}{dx}P(x) $$

If we evaluate the CDF, $P(r)$, at $r = 1.0$, we get:

$$ P(1.0) = \frac{1}{4} $$

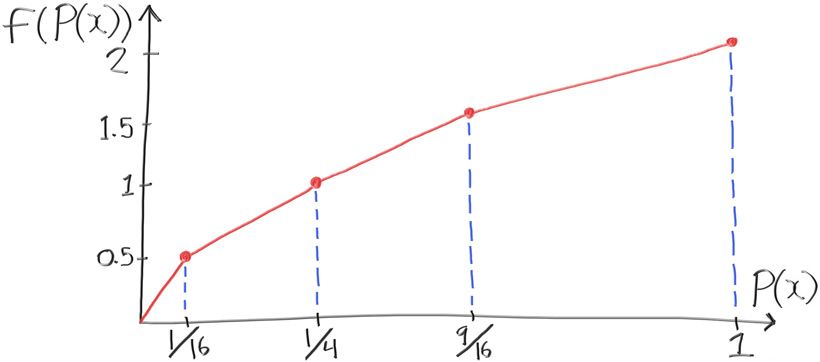

This says a random variable plucked from our PDF has a 25% chance of being 1 or lower. We want a

function $f(d)$ that takes a uniform distribution between 0 and 1 (i.e f(random_double())), and

returns a random value according to a distribution that has the CDF $P(x) = \frac{x^2}{4}$. We don’t

know yet know what the function $f(d)$ is analytically, but we do know that 25% of what it returns

should be less than 1.0, and 75% should be above 1.0. Likewise, we know that 50% of what it returns

should be less than $\sqrt{2}$, and 50% should be above $\sqrt{2}$. If $f(d)$ monotonically

increases, then we would expect $f(0.25) = 1.0$ and $f(0.5) = \sqrt{2}$. This can be generalized to

figure out $f(d)$ for every possible input:

$$ f(P(x)) = x $$

Let's take some more samples:

$$ P(0.0) = 0 $$

$$ P(0.5) = \frac{1}{16} $$

$$ P(1.0) = \frac{1}{4} $$

$$ P(1.5) = \frac{9}{16} $$

$$ P(2.0) = 1 $$

so, the function $f()$ has values

$$ f(P(0.0)) = f(0) = 0 $$

$$ f(P(0.5)) = f(\frac{1}{16}) = 0.5 $$

$$ f(P(1.0)) = f(\frac{1}{4}) = 1.0 $$

$$ f(P(1.5)) = f(\frac{9}{16}) = 1.5 $$

$$ f(P(2.0)) = f(1) = 2.0 $$

We could use these intermediate values and interpolate between them to approximate $f(d)$:

If you can't solve for the PDF analytically, then you can't solve for the CDF analytically. After all, the CDF is just the integral of the PDF. However, you can still create a distribution that approximates the PDF. If you take a bunch of samples from the random function you want the PDF from, you can approximate the PDF by getting a histogram of the samples and then converting to a PDF. Alternatively, you can do as we did above and sort all of your samples.

Looking closer at the equality:

$$ f(P(x)) = x $$

That just means that $f()$ just undoes whatever $P()$ does. So, $f()$ is the inverse function:

$$ f(d) = P^{-1}(x) $$

For our purposes, if we have PDF $p()$ and cumulative distribution function $P()$, we can use this "inverse function" with a random number to get what we want:

$$ f(d) = P^{-1} (\operatorname{random_double}()) $$

For our PDF $p(r) = r/2$, and corresponding $P(r)$, we need to compute the inverse of $P(r)$. If we have

$$ y = \frac{r^2}{4} $$

we get the inverse by solving for $r$ in terms of $y$:

$$ r = \sqrt{4y} $$

Which means the inverse of our CDF is defined as

$$ P^{-1}(r) = \sqrt{4y} $$

Thus our random number generator with density $p(r)$ can be created with:

$$ f(d) = \sqrt{4\cdot\operatorname{random_double}()} $$

Note that this ranges from 0 to 2 as we hoped, and if we check our work, we replace

random_double() with $1/4$ to get 1, and also replace with $1/2$ to get $\sqrt{2}$, just as

expected.

Importance Sampling

You should now have a decent understanding of how to take an analytical PDF and generate a function that produces random numbers with that distribution. We return to our original integral and try it with a few different PDFs to get a better understanding:

$$ I = \int_{0}^{2} x^2 dx $$

The last time that we tried to solve for the integral we used a Monte Carlo approach, uniformly sampling from the interval $[0, 2]$. We didn't know it at the time, but we were implicitly using a uniform PDF between 0 and 2. This means that we're using a PDF = $1/2$ over the range $[0,2]$, which means the CDF is $P(x) = x/2$, so $f(d) = 2d$. Knowing this, we can make this uniform PDF explicit:

#include "rtweekend.h"

#include <iostream>

#include <iomanip>

#include <math.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

double f(double d) {

return 2.0 * d;

}

double pdf(double x) {

return 0.5;

}

int main() {

int N = 1000000;

auto sum = 0.0;

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

auto x = f(random_double());

sum += x*x / pdf(x);

}

std::cout << std::fixed << std::setprecision(12);

std::cout << "I = " << sum / N << '\n';

}

There are a couple of important things to emphasize. Every value of $x$ represents one sample of the

function $x^2$ within the distribution $[0, 2]$. We use a function $f$ to randomly select samples

from within this distribution. We were previously multiplying the average over the interval

(sum / N) times the length of the interval (b - a) to arrive at the final answer. Here, we

don't need to multiply by the interval length--that is, we no longer need to multiply the average

by $2$.

We need to account for the nonuniformity of the PDF of $x$. Failing to account for this

nonuniformity will introduce bias in our scene. Indeed, this bias is the source of our inaccurately

bright image--if we account for nonuniformity, we will get accurate results. The PDF will "steer"

samples toward specific parts of the distribution, which will cause us to converge faster, but at

the cost of introducing bias. To remove this bias, we need to down-weight where we sample more

frequently, and to up-weight where we sample less frequently. For our new nonuniform random number

generator, the PDF defines how much or how little we sample a specific portion.

So the weighting function should be proportional to $1/\mathit{pdf}$.

In fact it is exactly $1/\mathit{pdf}$.

This is why we divide x*x by pdf(x).

We can try to solve for the integral using the linear PDF $p(r) = \frac{r}{2}$, for which we were able to solve for the CDF and its inverse. To do that, all we need to do is replace the functions $f = \sqrt{4d}$ and $pdf = x/2$.

double f(double d) {

return sqrt(4.0 * d);

}

double pdf(double x) {

return x / 2.0;

}

int main() {

int N = 1000000;

auto sum = 0.0;

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

auto x = f(random_double());

sum += x*x / pdf(x);

}

std::cout << std::fixed << std::setprecision(12);

std::cout << "I = " << sum / N << '\n';

}

If you compared the runs from the uniform PDF and the linear PDF, you would have probably found that the linear PDF converged faster. If you think about it, a linear PDF is probably a better approximation for a quadratic function than a uniform PDF, so you would expect it to converge faster. If that's the case, then we should just try to make the PDF match the integrand by turning the PDF into a quadratic function:

$$ p(r)=\begin{cases}

0 & r < 0 \\

C \cdot r^2 & 0 \leq r \leq 2 \\

0 & 2 < r \\

\end{cases}

$$

Like the linear PDF, we'll solve for the constant $C$ by integrating to 1 over the interval:

$$ 1 = \int_{0}^{2} C \cdot r^2 dr $$

$$ = C \cdot \int_{0}^{2} r^2 dr $$

$$ = C \cdot \frac{r^3}{3} \Big|_{0}^{2} $$

$$ = C ( \frac{2^3}{3} - \frac{0}{3} ) $$

$$ C = \frac{3}{8} $$

Which gives us:

$$ p(r)=\begin{cases}

0 & r < 0 \\

\frac{3}{8} r^2 & 0 \leq r \leq 2 \\

0 & 2 < r \\

\end{cases}

$$

And we get the corresponding CDF:

$$ P(r) = \frac{r^3}{8} $$

and

$$ P^{-1}(x) = f(d) = 8d^\frac{1}{3} $$

For just one sample we get:

double f(double d) {

return 8.0 * pow(d, 1.0/3.0);

}

double pdf(double x) {

return (3.0/8.0) * x*x;

}

int main() {

int N = 1;

auto sum = 0.0;

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

auto x = f(random_double()));

sum += x*x / pdf(x);

}

std::cout << std::fixed << std::setprecision(12);

std::cout << "I = " << sum / N << '\n';

}

This always returns the exact answer. Which, honestly, feels a bit like magic.

A nonuniform PDF "steers" more samples to where the PDF is big, and fewer samples to where the PDF is small. By this sampling, we would expect less noise in the places where the PDF is big and more noise where the PDF is small. If we choose a PDF that is higher in the parts of the scene that have higher noise, and is smaller in the parts of the scene that have lower noise, we'll be able to reduce the total noise of the scene with fewer samples. This means that we will be able to converge to the correct scene faster than with a uniform PDF. In effect, we are steering our samples toward the parts of the distribution that are more important. This is why using a carefully chosen nonuniform PDF is usually called importance sampling.

In all of the examples given, we always converged to the correct answer of $8/3$. We got the same answer when we used both a uniform PDF and the "correct" PDF ($i.e. f(d)=8d^{\frac{1}{3}}$). While they both converged to the same answer, the uniform PDF took much longer. After all, we only needed a single sample from the PDF that perfectly matched the integral. This should make sense, as we were choosing to sample the important parts of the distribution more often, whereas the uniform PDF just sampled the whole distribution equally, without taking importance into account.

Indeed, this is the case for any PDF that you create--they will all converge eventually. This is just another part of the power of the Monte Carlo algorithm. Even the naive PDF where we solved for the 50% value and split the distribution into two halves: $[0, \sqrt{2}]$ and $[\sqrt{2}, 2]$. That PDF will converge. Hopefully you should have an intuition as to why that PDF will converge faster than a pure uniform PDF, but slower than the linear PDF ($i.e. f(d) = \sqrt{4d}$).

The perfect importance sampling is only possible when we already know the answer (we got $P$ by integrating $p$ analytically), but it’s a good exercise to make sure our code works.

Let's review the main concepts that underlie Monte Carlo ray tracers:

- You have an integral of $f(x)$ over some domain $[a,b]$

- You pick a PDF $p$ that is non-zero and non-negative over $[a,b]$

- You average a whole ton of $\frac{f(r)}{p(r)}$ where $r$ is a random number with PDF $p$.

Any choice of PDF $p$ will always converge to the right answer, but the closer that $p$ approximates $f$, the faster that it will converge.