A Simple Monte Carlo Program

Let’s start with one of the simplest Monte Carlo programs. If you're not familiar with Monte Carlo programs, then it'll be good to pause and catch you up. There are two kinds of randomized algorithms: Monte Carlo and Las Vegas. Randomized algorithms can be found everywhere in computer graphics, so getting a decent foundation isn't a bad idea. A randomized algorithm uses some amount of randomness in its computation. A Las Vegas (LV) random algorithm always produces the correct result, whereas a Monte Carlo (MC) algorithm may produce a correct result--and frequently gets it wrong! But for especially complicated problems such as ray tracing, we may not place as huge a priority on being perfectly exact as on getting an answer in a reasonable amount of time. LV algorithms will eventually arrive at the correct result, but we can't make too many guarantees on how long it will take to get there. The classic example of an LV algorithm is the quicksort sorting algorithm. The quicksort algorithm will always complete with a fully sorted list, but, the time it takes to complete is random. Another good example of an LV algorithm is the code that we use to pick a random point in a unit sphere:

inline vec3 random_in_unit_sphere() {

while (true) {

auto p = vec3::random(-1,1);

if (p.length_squared() < 1)

return p;

}

}

This code will always eventually arrive at a random point in the unit sphere, but we can't say beforehand how long it'll take. It may take only 1 iteration, it may take 2, 3, 4, or even longer. Whereas, an MC program will give a statistical estimate of an answer, and this estimate will get more and more accurate the longer you run it. Which means that at a certain point, we can just decide that the answer is accurate enough and call it quits. This basic characteristic of simple programs producing noisy but ever-better answers is what MC is all about, and is especially good for applications like graphics where great accuracy is not needed.

Estimating Pi

The canonical example of a Monte Carlo algorithm is estimating $\pi$, so let's do that. There are many ways to estimate $\pi$, with the Buffon Needle problem being a classic case study. We’ll do a variation inspired by this method. Suppose you have a circle inscribed inside a square:

Now, suppose you pick random points inside the square. The fraction of those random points that end up inside the circle should be proportional to the area of the circle. The exact fraction should in fact be the ratio of the circle area to the square area:

$$ \frac{\pi r^2}{(2r)^2} = \frac{\pi}{4} $$

Since the $r$ cancels out, we can pick whatever is computationally convenient. Let’s go with $r=1$, centered at the origin:

#include "rtweekend.h"

#include <iostream>

#include <iomanip>

#include <math.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main() {

int N = 100000;

int inside_circle = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

auto x = random_double(-1,1);

auto y = random_double(-1,1);

if (x*x + y*y < 1)

inside_circle++;

}

std::cout << std::fixed << std::setprecision(12);

std::cout << "Estimate of Pi = " << (4.0 * inside_circle) / N << '\n';

}

The answer of $\pi$ found will vary from computer to computer based on the initial random seed.

On my computer, this gives me the answer Estimate of Pi = 3.143760000000.

Showing Convergence

If we change the program to run forever and just print out a running estimate:

#include "rtweekend.h"

#include <iostream>

#include <iomanip>

#include <math.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main() {

int inside_circle = 0;

int runs = 0;

std::cout << std::fixed << std::setprecision(12);

while (true) {

runs++;

auto x = random_double(-1,1);

auto y = random_double(-1,1);

if (x*x + y*y < 1)

inside_circle++;

if (runs % 100000 == 0)

std::cout << "Estimate of Pi = "

<< (4.0 * inside_circle) / runs

<< '\n';

}

}

Stratified Samples (Jittering)

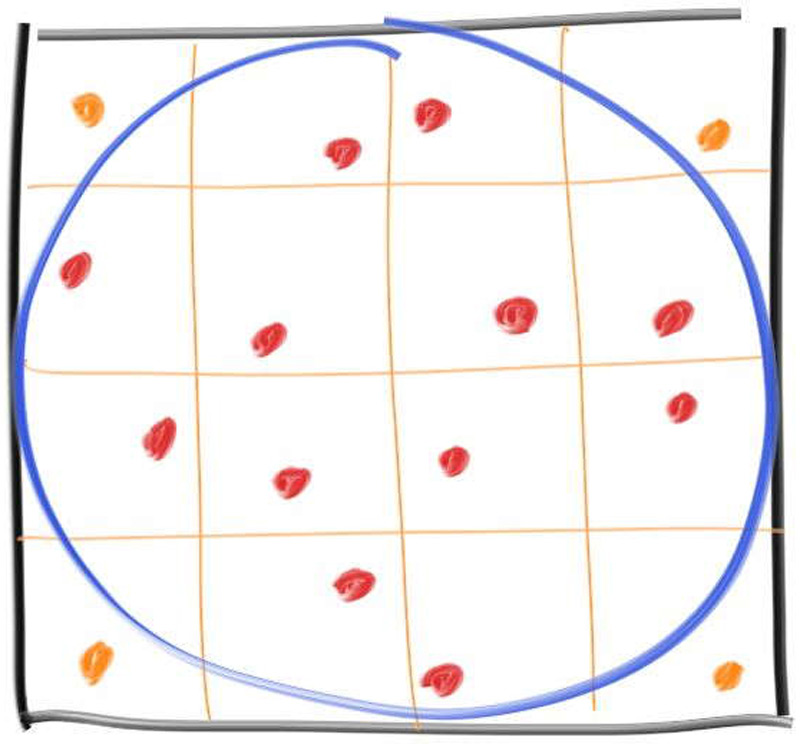

We get very quickly near $\pi$, and then more slowly zero in on it. This is an example of the Law of Diminishing Returns, where each sample helps less than the last. This is the worst part of Monte Carlo. We can mitigate this diminishing return by stratifying the samples (often called jittering), where instead of taking random samples, we take a grid and take one sample within each:

This changes the sample generation, but we need to know how many samples we are taking in advance because we need to know the grid. Let’s take a million and try it both ways:

#include "rtweekend.h"

#include <iostream>

#include <iomanip>

int main() {

int inside_circle = 0;

int inside_circle_stratified = 0;

int sqrt_N = 1000;

for (int i = 0; i < sqrt_N; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < sqrt_N; j++) {

auto x = random_double(-1,1);

auto y = random_double(-1,1);

if (x*x + y*y < 1)

inside_circle++;

x = 2*((i + random_double()) / sqrt_N) - 1;

y = 2*((j + random_double()) / sqrt_N) - 1;

if (x*x + y*y < 1)

inside_circle_stratified++;

}

}

std::cout << std::fixed << std::setprecision(12);

std::cout

<< "Regular Estimate of Pi = "

<< (4.0 * inside_circle) / (sqrt_N*sqrt_N) << '\n'

<< "Stratified Estimate of Pi = "

<< (4.0 * inside_circle_stratified) / (sqrt_N*sqrt_N) << '\n';

}

On my computer, I get:

Where the first 12 decimal places of pi are:

Interestingly, the stratified method is not only better, it converges with a better asymptotic rate! Unfortunately, this advantage decreases with the dimension of the problem (so for example, with the 3D sphere volume version the gap would be less). This is called the Curse of Dimensionality. Ray tracing is a very high-dimensional algorithm, where each reflection adds two new dimensions: $\phi_o$ and $\theta_o$. We won't be stratifying the output reflection angle in this book, simply because it is a little bit too complicated to cover, but there is a lot of interesting research currently happening in this space.

As an intermediary, we'll be stratifying the locations of the sampling positions around each pixel location.

#include "rtweekend.h"

#include "camera.h"

#include "color.h"

#include "hittable_list.h"

#include "material.h"

#include "quad.h"

#include "sphere.h"

int main() {

hittable_list world;

auto red = make_shared<lambertian>(color(.65, .05, .05));

auto white = make_shared<lambertian>(color(.73, .73, .73));

auto green = make_shared<lambertian>(color(.12, .45, .15));

auto light = make_shared<diffuse_light>(color(15, 15, 15));

// Cornell box sides

world.add(make_shared<quad>(point3(555,0,0), vec3(0,0,555), vec3(0,555,0), green));

world.add(make_shared<quad>(point3(0,0,555), vec3(0,0,-555), vec3(0,555,0), red));

world.add(make_shared<quad>(point3(0,555,0), vec3(555,0,0), vec3(0,0,555), white));

world.add(make_shared<quad>(point3(0,0,555), vec3(555,0,0), vec3(0,0,-555), white));

world.add(make_shared<quad>(point3(555,0,555), vec3(-555,0,0), vec3(0,555,0), white));

// Light

world.add(make_shared<quad>(point3(213,554,227), vec3(130,0,0), vec3(0,0,105), light));

// Box 1

shared_ptr<hittable> box1 = box(point3(0,0,0), point3(165,330,165), white);

box1 = make_shared<rotate_y>(box1, 15);

box1 = make_shared<translate>(box1, vec3(265,0,295));

world.add(box1);

// Box 2

shared_ptr<hittable> box2 = box(point3(0,0,0), point3(165,165,165), white);

box2 = make_shared<rotate_y>(box2, -18);

box2 = make_shared<translate>(box2, vec3(130,0,65));

world.add(box2);

camera cam;

cam.aspect_ratio = 1.0;

cam.image_width = 600;

cam.samples_per_pixel = 64;

cam.max_depth = 50;

cam.background = color(0,0,0);

cam.vfov = 40;

cam.lookfrom = point3(278, 278, -800);

cam.lookat = point3(278, 278, 0);

cam.vup = vec3(0, 1, 0);

cam.defocus_angle = 0;

cam.render(world, lights);

}

class camera {

public:

...

void render(const hittable& world) {

initialize();

std::cout << "P3\n" << image_width << ' ' << image_height << "\n255\n";

for (int j = 0; j < image_height; ++j) {

std::clog << "\rScanlines remaining: " << (image_height - j) << ' ' << std::flush;

for (int i = 0; i < image_width; ++i) {

color pixel_color(0,0,0);

for (int s_j = 0; s_j < sqrt_spp; ++s_j) {

for (int s_i = 0; s_i < sqrt_spp; ++s_i) {

ray r = get_ray(i, j, s_i, s_j);

pixel_color += ray_color(r, max_depth, world);

}

}

write_color(std::cout, pixel_color, samples_per_pixel);

}

}

std::clog << "\rDone. \n";

}

...

private:

...

ray get_ray(int i, int j, int s_i, int s_j) const {

// Get a randomly-sampled camera ray for the pixel at location i,j, originating from

// the camera defocus disk, and randomly sampled around the pixel location.

auto pixel_center = pixel00_loc + (i * pixel_delta_u) + (j * pixel_delta_v);

auto pixel_sample = pixel_center + pixel_sample_square(s_i, s_j);

auto ray_origin = (defocus_angle <= 0) ? center : defocus_disk_sample();

auto ray_direction = pixel_sample - ray_origin;

auto ray_time = random_double();

return ray(ray_origin, ray_direction, ray_time);

}

vec3 pixel_sample_square(int s_i, int s_j) const {

// Returns a random point in the square surrounding a pixel at the origin, given

// the two subpixel indices.

auto px = -0.5 + recip_sqrt_spp * (s_i + random_double());

auto py = -0.5 + recip_sqrt_spp * (s_j + random_double());

return (px * pixel_delta_u) + (py * pixel_delta_v);

}

...

};

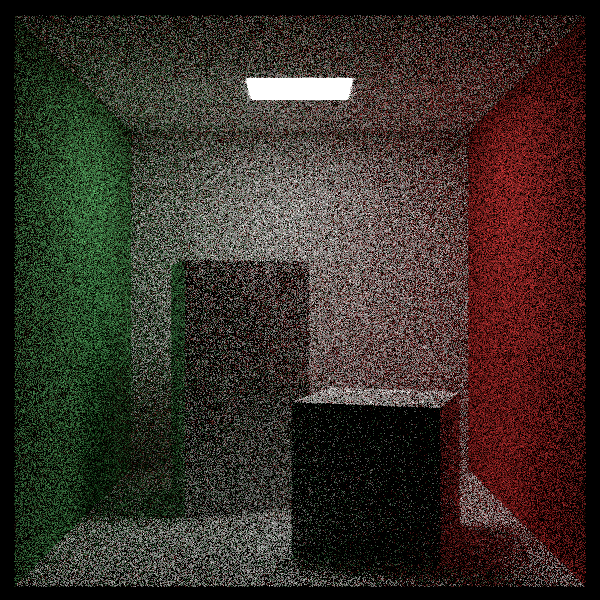

If we compare the results from without stratification:

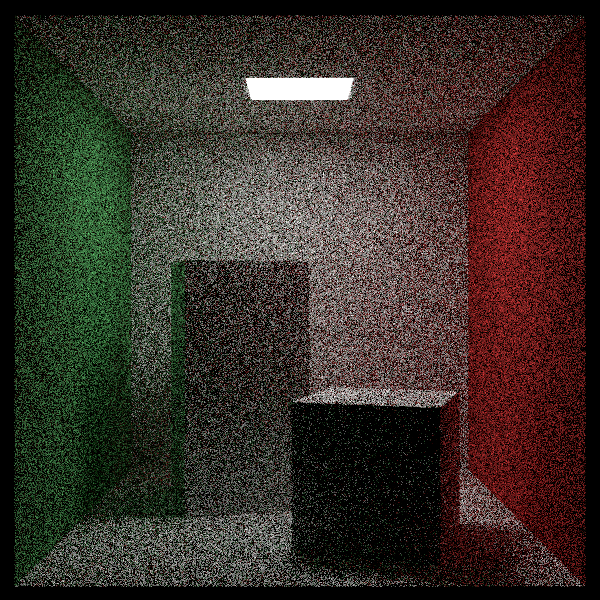

To after, with stratification:

You should, if you squint, be able to see sharper contrast at the edges of planes and at the edges of boxes. The effect will be more pronounced at locations that have a higher frequency of change. High frequency change can also be thought of as high information density. For our cornell box scene, all of our materials are matte, with a soft area light overhead, so the only locations of high information density are at the edges of objects. The effect will be more obvious with textures and reflective materials.

If you are ever doing single-reflection or shadowing or some strictly 2D problem, you definitely want to stratify.