Texture Mapping

Texture mapping in computer graphics is the process of applying a material effect to an object in the scene. The "texture" part is the effect, and the "mapping" part is in the mathematical sense of mapping one space onto another. This effect could be any material property: color, shininess, bump geometry (called Bump Mapping), or even material existence (to create cut-out regions of the surface).

The most common type of texture mapping maps an image onto the surface of an object, defining the color at each point on the object’s surface. In practice, we implement the process in reverse: given some point on the object, we’ll look up the color defined by the texture map.

To begin with, we'll make the texture colors procedural, and will create a texture map of constant color. Most programs keep constant RGB colors and textures in different classes, so feel free to do something different, but I am a big believer in this architecture because it's great being able to make any color a texture.

In order to perform the texture lookup, we need a texture coordinate. This coordinate can be defined in many ways, and we'll develop this idea as we progress. For now, we'll pass in two dimensional texture coordinates. By convention, texture coordinates are named $u$ and $v$. For a constant texture, every $(u,v)$ pair yields a constant color, so we can actually ignore the coordinates completely. However, other texture types will need these coordinates, so we keep these in the method interface.

The primary method of our texture classes is the color value(...) method, which returns the

texture color given the input coordinates. In addition to taking the point's texture coordinates $u$

and $v$, we also provide the position of the point in question, for reasons that will become

apparent later.

Co|nstant Color Texture

#ifndef TEXTURE_H

#define TEXTURE_H

#include "rtweekend.h"

class texture {

public:

virtual ~texture() = default;

virtual color value(double u, double v, const point3& p) const = 0;

};

class solid_color : public texture {

public:

solid_color(color c) : color_value(c) {}

solid_color(double red, double green, double blue) : solid_color(color(red,green,blue)) {}

color value(double u, double v, const point3& p) const override {

return color_value;

}

private:

color color_value;

};

#endif

We'll need to update the hit_record structure to store the $u,v$ surface coordinates of the

ray-object hit point.

class hit_record {

public:

vec3 p;

vec3 normal;

shared_ptr<material> mat;

double t;

double u;

double v;

bool front_face;

...

We will also need to compute $(u,v)$ texture coordinates for a given point on each type of

hittable.

Solid Textures: A Checker Texture

A solid (or spatial) texture depends only on the position of each point in 3D space. You can think of a solid texture as if it's coloring all of the points in space itself, instead of coloring a given object in that space. For this reason, the object can move through the colors of the texture as it changes position, though usually you would to fix the relationship between the object and the solid texture.

To explore spatial textures, we'll implement a spatial checker_texture class, which implements a

three-dimensional checker pattern. Since a spatial texture function is driven by a given position in

space, the texture value() function ignores the u and v parameters, and uses only the p

parameter.

To accomplish the checkered pattern, we'll first compute the floor of each component of the input point. We could truncate the coordinates, but that would pull values toward zero, which would give us the same color on both sides of zero. The floor function will always shift values to the integer value on the left (toward negative infinity). Given these three integer results ($\lfloor x \rfloor, \lfloor y \rfloor, \lfloor z \rfloor$) we take their sum and compute the result modulo two, which gives us either 0 or 1. Zero maps to the even color, and one to the odd color.

Finally, we add a scaling factor to the texture, to allow us to control the size of the checker pattern in the scene.

class checker_texture : public texture {

public:

checker_texture(double _scale, shared_ptr<texture> _even, shared_ptr<texture> _odd)

: inv_scale(1.0 / _scale), even(_even), odd(_odd) {}

checker_texture(double _scale, color c1, color c2)

: inv_scale(1.0 / _scale),

even(make_shared<solid_color>(c1)),

odd(make_shared<solid_color>(c2))

{}

color value(double u, double v, const point3& p) const override {

auto xInteger = static_cast<int>(std::floor(inv_scale * p.x()));

auto yInteger = static_cast<int>(std::floor(inv_scale * p.y()));

auto zInteger = static_cast<int>(std::floor(inv_scale * p.z()));

bool isEven = (xInteger + yInteger + zInteger) % 2 == 0;

return isEven ? even->value(u, v, p) : odd->value(u, v, p);

}

private:

double inv_scale;

shared_ptr<texture> even;

shared_ptr<texture> odd;

};

Those checker odd/even parameters can point to a constant texture or to some other procedural texture. This is in the spirit of shader networks introduced by Pat Hanrahan back in the 1980s.

If we add this to our random_scene() function’s base sphere:

...

#include "texture.h"

void random_spheres() {

hittable_list world;

auto checker = make_shared<checker_texture>(0.32, color(.2, .3, .1), color(.9, .9, .9));

world.add(make_shared<sphere>(point3(0,-1000,0), 1000, make_shared<lambertian>(checker)));

for (int a = -11; a < 11; a++) {

...

}

...

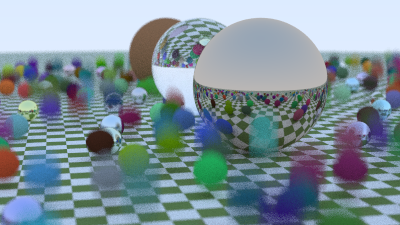

We get:

Rendering The Solid Checker Texture

We're going to add a second scene to our program, and will add more scenes after that as we progress through this book. To help with this, we'll set up a switch statement to select the desired scene for a given run. It's a crude approach, but we're trying to keep things dead simple and focus on the raytracing. You may want to use a different approach in your own raytracer, such as supporting command-line arguments.

Here's what our main.cc looks like after refactoring for our single random spheres scene. Rename

main() to random_spheres(), and add a new main() function to call it:

#include "rtweekend.h"

#include "camera.h"

#include "color.h"

#include "hittable_list.h"

#include "material.h"

#include "sphere.h"

void random_spheres() {

hittable_list world;

auto ground_material = make_shared<lambertian>(color(0.5, 0.5, 0.5));

world.add(make_shared<sphere>(point3(0,-1000,0), 1000, ground_material));

...

cam.render(world);

}

int main() {

random_spheres();

}

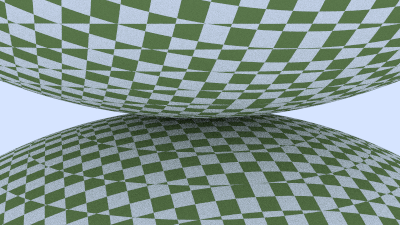

Now add a scene with two checkered spheres, one atop the other.

#include "rtweekend.h"

#include "camera.h"

#include "color.h"

#include "hittable_list.h"

#include "material.h"

#include "sphere.h"

void random_spheres() {

...

}

void two_spheres() {

hittable_list world;

auto checker = make_shared<checker_texture>(0.8, color(.2, .3, .1), color(.9, .9, .9));

world.add(make_shared<sphere>(point3(0,-10, 0), 10, make_shared<lambertian>(checker)));

world.add(make_shared<sphere>(point3(0, 10, 0), 10, make_shared<lambertian>(checker)));

camera cam;

cam.aspect_ratio = 16.0 / 9.0;

cam.image_width = 400;

cam.samples_per_pixel = 100;

cam.max_depth = 50;

cam.vfov = 20;

cam.lookfrom = point3(13,2,3);

cam.lookat = point3(0,0,0);

cam.vup = vec3(0,1,0);

cam.defocus_angle = 0;

cam.render(world);

}

int main() {

switch (2) {

case 1: random_spheres(); break;

case 2: two_spheres(); break;

}

}

We get this result:

You may think the result looks a bit odd. Since checker_texture is a spatial texture, we're really

looking at the surface of the sphere cutting through the three-dimensional checker space. There are

many situations where this is perfect, or at least sufficient. In many other situations, we really

want to get a consistent effect on the surface of our objects. That approach is covered next.

Texture Coordinates for Spheres

Constant-color textures use no coordinates. Solid (or spatial) textures use the coordinates of a point in space. Now it's time to make use of the $u,v$ texture coordinates. These coordinates specify the location on 2D source image (or in some 2D parameterized space). To get this, we need a way to find the $u,v$ coordinates of any point on the surface of a 3D object. This mapping is completely arbitrary, but generally you'd like to cover the entire surface, and be able to scale, orient and stretch the 2D image in a way that makes some sense. We'll start with deriving a scheme to get the $u,v$ coordinates of a sphere.

For spheres, texture coordinates are usually based on some form of longitude and latitude, i.e., spherical coordinates. So we compute $(\theta,\phi)$ in spherical coordinates, where $\theta$ is the angle up from the bottom pole (that is, up from -Y), and $\phi$ is the angle around the Y-axis (from -X to +Z to +X to -Z back to -X).

We want to map $\theta$ and $\phi$ to texture coordinates $u$ and $v$ each in $[0,1]$, where $(u=0,v=0)$ maps to the bottom-left corner of the texture. Thus the normalization from $(\theta,\phi)$ to $(u,v)$ would be:

$$ u = \frac{\phi}{2\pi} $$ $$ v = \frac{\theta}{\pi} $$

To compute $\theta$ and $\phi$ for a given point on the unit sphere centered at the origin, we start with the equations for the corresponding Cartesian coordinates:

$$ \begin{align} y &= -\cos(\theta) \ x &= -\cos(\phi) \sin(\theta) \ z &= \quad\sin(\phi) \sin(\theta) \end{align} $$

We need to invert these equations to solve for $\theta$ and $\phi$. Because of the lovely <cmath>

function atan2(), which takes any pair of numbers proportional to sine and cosine and returns the

angle, we can pass in $x$ and $z$ (the $\sin(\theta)$ cancel) to solve for $\phi$:

$$ \phi = \operatorname{atan2}(z, -x) $$

atan2() returns values in the range $-\pi$ to $\pi$, but they go from 0 to $\pi$, then flip to

$-\pi$ and proceed back to zero. While this is mathematically correct, we want $u$ to range from $0$

to $1$, not from $0$ to $1/2$ and then from $-1/2$ to $0$. Fortunately,

$$ \operatorname{atan2}(a,b) = \operatorname{atan2}(-a,-b) + \pi, $$

and the second formulation yields values from $0$ continuously to $2\pi$. Thus, we can compute $\phi$ as

$$ \phi = \operatorname{atan2}(-z, x) + \pi $$

The derivation for $\theta$ is more straightforward:

$$ \theta = \arccos(-y) $$

So for a sphere, the $(u,v)$ coord computation is accomplished by a utility function that takes points on the unit sphere centered at the origin, and computes $u$ and $v$:

class sphere : public hittable {

...

private:

...

static void get_sphere_uv(const point3& p, double& u, double& v) {

// p: a given point on the sphere of radius one, centered at the origin.

// u: returned value [0,1] of angle around the Y axis from X=-1.

// v: returned value [0,1] of angle from Y=-1 to Y=+1.

// <1 0 0> yields <0.50 0.50> <-1 0 0> yields <0.00 0.50>

// <0 1 0> yields <0.50 1.00> < 0 -1 0> yields <0.50 0.00>

// <0 0 1> yields <0.25 0.50> < 0 0 -1> yields <0.75 0.50>

auto theta = acos(-p.y());

auto phi = atan2(-p.z(), p.x()) + pi;

u = phi / (2*pi);

v = theta / pi;

}

};

Update the sphere::hit() function to use this function to update the hit record UV coordinates.

class sphere : public hittable {

public:

...

bool hit(const ray& r, interval ray_t, hit_record& rec) const override {

...

rec.t = root;

rec.p = r.at(rec.t);

vec3 outward_normal = (rec.p - center) / radius;

rec.set_face_normal(r, outward_normal);

get_sphere_uv(outward_normal, rec.u, rec.v);

rec.mat = mat;

return true;

}

...

};

Now we can make textured materials by replacing the const color& a with a texture pointer:

#include "texture.h"

...

class lambertian : public material {

public:

lambertian(const color& a) : albedo(make_shared<solid_color>(a)) {}

lambertian(shared_ptr<texture> a) : albedo(a) {}

bool scatter(const ray& r_in, const hit_record& rec, color& attenuation, ray& scattered)

const override {

auto scatter_direction = rec.normal + random_unit_vector();

// Catch degenerate scatter direction

if (scatter_direction.near_zero())

scatter_direction = rec.normal;

scattered = ray(rec.p, scatter_direction, r_in.time());

attenuation = albedo->value(rec.u, rec.v, rec.p);

return true;

}

private:

shared_ptr<texture> albedo;

};

From the hitpoint $\mathbf{P}$, we compute the surface coordinates $(u,v)$. We then use these to index into our procedural solid texture (like marble). We can also read in an image and use the 2D $(u,v)$ texture coordinate to index into the image.

A direct way to use scaled $(u,v)$ in an image is to round the $u$ and $v$ to integers, and use that as $(i,j)$ pixels. This is awkward, because we don’t want to have to change the code when we change image resolution. So instead, one of the the most universal unofficial standards in graphics is to use texture coordinates instead of image pixel coordinates. These are just some form of fractional position in the image. For example, for pixel $(i,j)$ in an $N_x$ by $N_y$ image, the image texture position is:

$$ u = \frac{i}{N_x-1} $$ $$ v = \frac{j}{N_y-1} $$

This is just a fractional position.

Accessing Texture Image Data

Now it's time to create a texture class that holds an image. I am going to use my favorite image

utility, [stb_image][]. It reads image data into a big array of unsigned chars. These are just

packed RGBs with each component in the range [0,255] (black to full white). To help make loading our

image files even easier, we provide a helper class to manage all this -- rtw_image. The following

listing assumes that you have copied the stb_image.h header into a folder called external.

Adjust according to your directory structure.

#ifndef RTW_STB_IMAGE_H

#define RTW_STB_IMAGE_H

// Disable strict warnings for this header from the Microsoft Visual C++ compiler.

#ifdef _MSC_VER

#pragma warning (push, 0)

#endif

#define STB_IMAGE_IMPLEMENTATION

#define STBI_FAILURE_USERMSG

#include "external/stb_image.h"

#include <cstdlib>

#include <iostream>

class rtw_image {

public:

rtw_image() : data(nullptr) {}

rtw_image(const char* image_filename) {

// Loads image data from the specified file. If the RTW_IMAGES environment variable is

// defined, looks only in that directory for the image file. If the image was not found,

// searches for the specified image file first from the current directory, then in the

// images/ subdirectory, then the _parent's_ images/ subdirectory, and then _that_

// parent, on so on, for six levels up. If the image was not loaded successfully,

// width() and height() will return 0.

auto filename = std::string(image_filename);

auto imagedir = getenv("RTW_IMAGES");

// Hunt for the image file in some likely locations.

if (imagedir && load(std::string(imagedir) + "/" + image_filename)) return;

if (load(filename)) return;

if (load("images/" + filename)) return;

if (load("../images/" + filename)) return;

if (load("../../images/" + filename)) return;

if (load("../../../images/" + filename)) return;

if (load("../../../../images/" + filename)) return;

if (load("../../../../../images/" + filename)) return;

if (load("../../../../../../images/" + filename)) return;

std::cerr << "ERROR: Could not load image file '" << image_filename << "'.\n";

}

~rtw_image() { STBI_FREE(data); }

bool load(const std::string filename) {

// Loads image data from the given file name. Returns true if the load succeeded.

auto n = bytes_per_pixel; // Dummy out parameter: original components per pixel

data = stbi_load(filename.c_str(), &image_width, &image_height, &n, bytes_per_pixel);

bytes_per_scanline = image_width * bytes_per_pixel;

return data != nullptr;

}

int width() const { return (data == nullptr) ? 0 : image_width; }

int height() const { return (data == nullptr) ? 0 : image_height; }

const unsigned char* pixel_data(int x, int y) const {

// Return the address of the three bytes of the pixel at x,y (or magenta if no data).

static unsigned char magenta[] = { 255, 0, 255 };

if (data == nullptr) return magenta;

x = clamp(x, 0, image_width);

y = clamp(y, 0, image_height);

return data + y*bytes_per_scanline + x*bytes_per_pixel;

}

private:

const int bytes_per_pixel = 3;

unsigned char *data;

int image_width, image_height;

int bytes_per_scanline;

static int clamp(int x, int low, int high) {

// Return the value clamped to the range [low, high).

if (x < low) return low;

if (x < high) return x;

return high - 1;

}

};

// Restore MSVC compiler warnings

#ifdef _MSC_VER

#pragma warning (pop)

#endif

#endif

If you are writing your implementation in a language other than C or C++, you'll need to locate (or write) an image loading library that provides similar functionality.

The image_texture class uses the rtw_image class:

#include "rtweekend.h"

#include "rtw_stb_image.h"

#include "perlin.h"

...

class image_texture : public texture {

public:

image_texture(const char* filename) : image(filename) {}

color value(double u, double v, const point3& p) const override {

// If we have no texture data, then return solid cyan as a debugging aid.

if (image.height() <= 0) return color(0,1,1);

// Clamp input texture coordinates to [0,1] x [1,0]

u = interval(0,1).clamp(u);

v = 1.0 - interval(0,1).clamp(v); // Flip V to image coordinates

auto i = static_cast<int>(u * image.width());

auto j = static_cast<int>(v * image.height());

auto pixel = image.pixel_data(i,j);

auto color_scale = 1.0 / 255.0;

return color(color_scale*pixel[0], color_scale*pixel[1], color_scale*pixel[2]);

}

private:

rtw_image image;

};

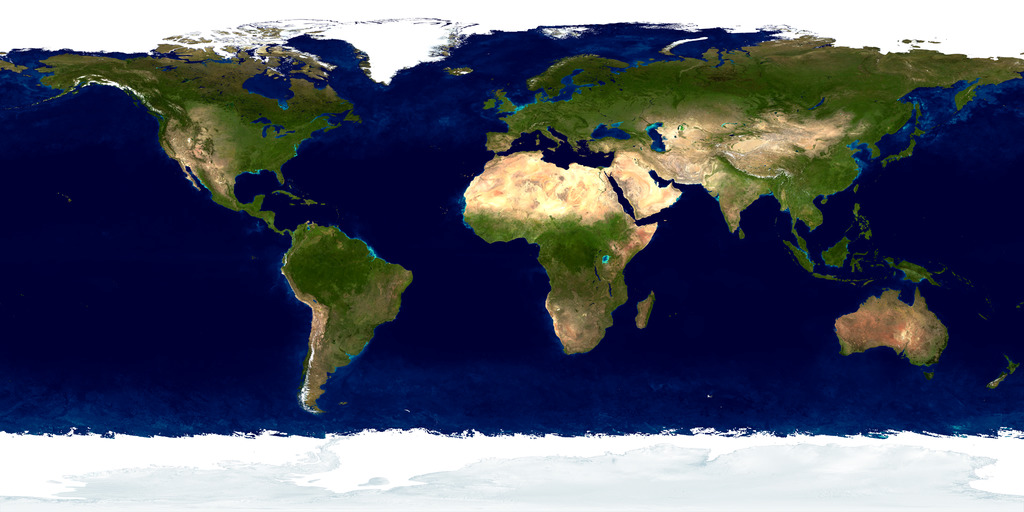

Rendering The Image Texture

I just grabbed a random earth map from the web -- any standard projection will do for our purposes.

Here's the code to read an image from a file and then assign it to a diffuse material:

void earth() {

auto earth_texture = make_shared<image_texture>("earthmap.jpg");

auto earth_surface = make_shared<lambertian>(earth_texture);

auto globe = make_shared<sphere>(point3(0,0,0), 2, earth_surface);

camera cam;

cam.aspect_ratio = 16.0 / 9.0;

cam.image_width = 400;

cam.samples_per_pixel = 100;

cam.max_depth = 50;

cam.vfov = 20;

cam.lookfrom = point3(0,0,12);

cam.lookat = point3(0,0,0);

cam.vup = vec3(0,1,0);

cam.defocus_angle = 0;

cam.render(hittable_list(globe));

}

int main() {

switch (3) {

case 1: random_spheres(); break;

case 2: two_spheres(); break;

case 3: earth(); break;

}

}

We start to see some of the power of all colors being textures -- we can assign any kind of texture to the lambertian material, and lambertian doesn’t need to be aware of it.

If the photo comes back with a large cyan sphere in the middle, then stb_image failed to find your

Earth map photo. The program will look for the file in the same directory as the executable. Make

sure to copy the Earth into your build directory, or rewrite earth() to point somewhere else.