Quadrilaterals

We've managed to get more than half way through this three-book series using spheres as our only geometric primitive. Time to add our second primitive: the quadrilateral.

Defining the Quadrilateral

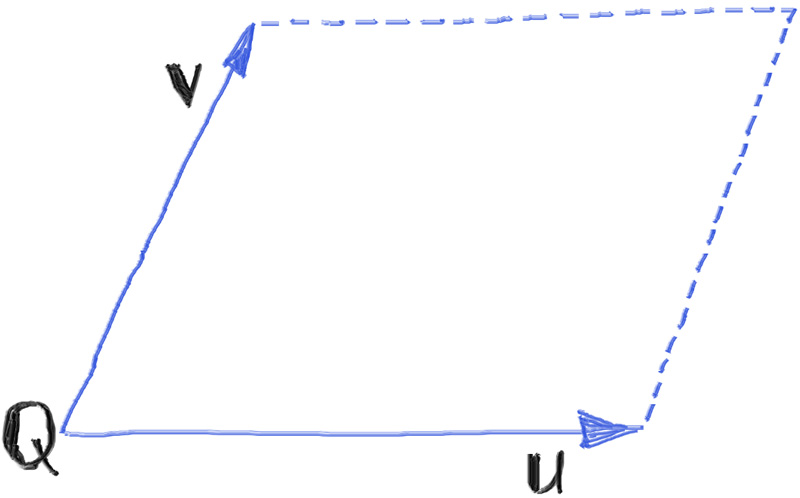

Though we'll name our new primitive a quad, it will technically be a parallelogram (opposite sides

are parallel) instead of a general quadrilateral. For our purposes, we'll use three geometric

entities to define a quad:

- $\mathbf{Q}$, the lower-left corner.

- $\mathbf{u}$, a vector representing the first side. $\mathbf{Q} + \mathbf{u}$ gives one of the corners adjacent to $\mathbf{Q}$.

- $\mathbf{v}$, a vector representing the second side. $\mathbf{Q} + \mathbf{v}$ gives the other corner adjacent to $\mathbf{Q}$.

The corner of the quad opposite $\mathbf{Q}$ is given by $\mathbf{Q} + \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{v}$. These values are three-dimensional, even though a quad itself is a two-dimensional object. For example, a quad with corner at the origin and extending two units in the Z direction and one unit in the Y direction would have values $\mathbf{Q} = (0,0,0), \mathbf{u} = (0,0,2), \text{and } \mathbf{v} = (0,1,0)$.

The following figure illustrates the quadrilateral components.

Quads are flat, so their axis-aligned bounding box will have zero thickness in one dimension if the

quad lies in the XY, YZ, or ZX plane. This can lead to numerical problems with ray intersection, but

we can address this by padding any zero-sized dimensions of the bounding box. Padding is fine

because we aren't changing the intersection of the quad; we're only expanding its bounding box to

remove the possibility of numerical problems, and the bounds are just a rough approximation to the

actual shape anyway. To this end, we add a new aabb::pad() method that remedies this situation:

...

class aabb {

public:

...

aabb(const aabb& box0, const aabb& box1) {

x = interval(box0.x, box1.x);

y = interval(box0.y, box1.y);

z = interval(box0.z, box1.z);

}

aabb pad() {

// Return an AABB that has no side narrower than some delta, padding if necessary.

double delta = 0.0001;

interval new_x = (x.size() >= delta) ? x : x.expand(delta);

interval new_y = (y.size() >= delta) ? y : y.expand(delta);

interval new_z = (z.size() >= delta) ? z : z.expand(delta);

return aabb(new_x, new_y, new_z);

}

Now we're ready for the first sketch of the new quad class:

#ifndef QUAD_H

#define QUAD_H

#include "rtweekend.h"

#include "hittable.h"

class quad : public hittable {

public:

quad(const point3& _Q, const vec3& _u, const vec3& _v, shared_ptr<material> m)

: Q(_Q), u(_u), v(_v), mat(m)

{

set_bounding_box();

}

virtual void set_bounding_box() {

bbox = aabb(Q, Q + u + v).pad();

}

aabb bounding_box() const override { return bbox; }

bool hit(const ray& r, interval ray_t, hit_record& rec) const override {

return false; // To be implemented

}

private:

point3 Q;

vec3 u, v;

shared_ptr<material> mat;

aabb bbox;

};

#endif

Ray-Plane Intersection

As you can see in the prior listing, quad::hit() remains to be implemented. Just as for spheres,

we need to determine whether a given ray intersects the primitive, and if so, the various properties

of that intersection (hit point, normal, texture coordinates and so forth).

Ray-quad intersection will be determined in three steps:

- finding the plane that contains that quad,

- solving for the intersection of a ray and the quad-containing plane,

- determining if the hit point lies inside the quad.

We'll first tackle the middle step, solving for general ray-plane intersection.

Spheres are generally the first ray tracing primitive taught because their implicit formula makes it so easy to solve for ray intersection. Like spheres, planes also have an implicit formula, and we can use their implicit formula to produce an algorithm that solves for ray-plane intersection. Indeed, ray-plane intersection is even easier to solve than ray-sphere intersection.

You may already know this implicit formula for a plane:

$$ Ax + By + Cz + D = 0 $$

where $A,B,C,D$ are just constants, and $x,y,z$ are the values of any point $(x,y,z)$ that lies on the plane. A plane is thus the set of all points $(x,y,z)$ that satisfy the formula above. It makes things slightly easier to use the alternate formulation:

$$ Ax + By + Cz = D $$

(We didn't flip the sign of D because it's just some constant that we'll figure out later.)

Here's an intuitive way to think of this formula: given the plane perpendicular to the normal vector $\mathbf{n} = (A,B,C)$, and the position vector $\mathbf{v} = (x,y,z)$ (that is, the vector from the origin to any point on the plane), then we can use the dot product to solve for $D$:

$$ \mathbf{n} \cdot \mathbf{v} = D $$

for any position on the plane. This is an equivalent formulation of the $Ax + By + Cz = D$ formula given above, only now in terms of vectors.

Now to find the intersection with some ray $\mathbf{R}(t) = \mathbf{P} + t\mathbf{d}$. Plugging in the ray equation, we get

$$ \mathbf{n} \cdot ( \mathbf{P} + t \mathbf{d} ) = D $$

Solving for $t$:

$$ \mathbf{n} \cdot \mathbf{P} + \mathbf{n} \cdot t \mathbf{d} = D $$

$$ \mathbf{n} \cdot \mathbf{P} + t(\mathbf{n} \cdot \mathbf{d}) = D $$

$$ t = \frac{D - \mathbf{n} \cdot \mathbf{P}}{\mathbf{n} \cdot \mathbf{d}} $$

This gives us $t$, which we can plug into the ray equation to find the point of intersection. Note that the denominator $\mathbf{n} \cdot \mathbf{d}$ will be zero if the ray is parallel to the plane. In this case, we can immediately record a miss between the ray and the plane. As for other primitives, if the ray $t$ parameter is less than the minimum acceptable value, we also record a miss.

All right, we can find the point of intersection between a ray and the plane that contains a given quadrilateral. In fact, we can use this approach to test any planar primitive, like triangles and disks (more on that later).

Finding the Plane That Contains a Given Quadrilateral

We've solved step two above: solving the ray-plane intersection, assuming we have the plane equation. To do this, we need to tackle step one above: finding the equation for the plane that contains the quad. We have quadrilateral parameters $\mathbf{Q}$, $\mathbf{u}$, and $\mathbf{v}$, and want the corresponding equation of the plane containing the quad defined by these three values.

Fortunately, this is very simple. Recall that in the equation $Ax + By + Cz = D$, $(A,B,C)$ represents the normal vector. To get this, we just use the cross product of the two side vectors $\mathbf{u}$ and $\mathbf{v}$:

$$ \mathbf{n} = \operatorname{unit_vector}(\mathbf{u} \times \mathbf{v}) $$

The plane is defined as all points $(x,y,z)$ that satisfy the equation $Ax + By + Cz = D$. Well, we know that $\mathbf{Q}$ lies on the plane, so that's enough to solve for $D$:

$$ \begin{align} D &= n_x Q_x + n_y Q_y + n_z Q_z \ &= \mathbf{n} \cdot \mathbf{Q} \ \end{align} $$

Add the planar values to the quad class:

class quad : public hittable {

public:

quad(const point3& _Q, const vec3& _u, const vec3& _v, shared_ptr<material> m)

: Q(_Q), u(_u), v(_v), mat(m)

{

auto n = cross(u, v);

normal = unit_vector(n);

D = dot(normal, Q);

set_bounding_box();

}

...

private:

point3 Q;

vec3 u, v;

shared_ptr<material> mat;

aabb bbox;

vec3 normal;

double D;

};

We will use the two values normal and D to find the point of intersection between a given ray

and the plane containing the quadrilateral.

As an incremental step, let's implement the hit() method to handle the infinite plane containing

our quadrilateral.

class quad : public hittable {

...

bool hit(const ray& r, interval ray_t, hit_record& rec) const override {

auto denom = dot(normal, r.direction());

// No hit if the ray is parallel to the plane.

if (fabs(denom) < 1e-8)

return false;

// Return false if the hit point parameter t is outside the ray interval.

auto t = (D - dot(normal, r.origin())) / denom;

if (!ray_t.contains(t))

return false;

auto intersection = r.at(t);

rec.t = t;

rec.p = intersection;

rec.mat = mat;

rec.set_face_normal(r, normal);

return true;

}

...

Orienting Points on The Plane

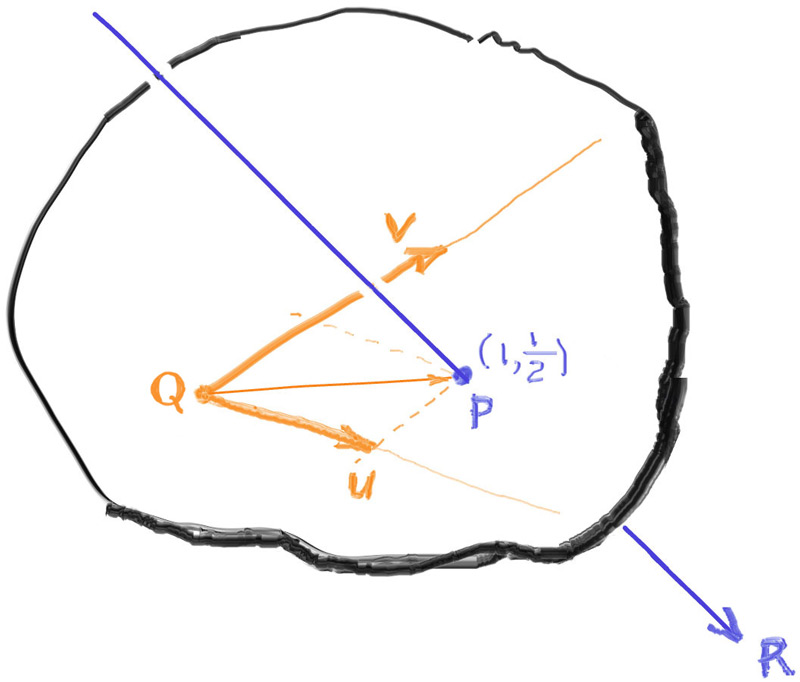

At this stage, the intersection point is on the plane that contains the quadrilateral, but it could be anywhere on the plane: the ray-plane intersection point will lie inside or outside the quadrilateral. We need to test for intersection points that lie inside the quadrilateral (hit), and reject points that lie outside (miss). To determine where a point lies relative to the quad, and to assign texture coordinates to the point of intersection, we need to orient the intersection point on the plane.

To do this, we'll construct a coordinate frame for the plane -- a way of orienting any point located on the plane. We've already been using a coordinate frame for our 3D space -- this is defined by an origin point $\mathbf{O}$ and three basis vectors $\mathbf{x}$, $\mathbf{y}$, and $\mathbf{z}$.

Since a plane is a 2D construct, we just need a plane origin point $\mathbf{Q}$ and two basis vectors: $\mathbf{u}$ and $\mathbf{v}$. Normally, axes are perpendicular to each other. However, this doesn't need to be the case in order to span the entire space -- you just need two axes that are not parallel to each other.

Consider figure [ray-plane] as an example. Ray $\mathbf{R}$ intersects the plane, yielding intersection point $\mathbf{P}$ (not to be confused with the ray origin point $\mathbf{P}$ above). Measuring against plane vectors $\mathbf{u}$ and $\mathbf{v}$, the intersection point $\mathbf{P}$ in the example above is at $\mathbf{Q} + (1)\mathbf{u} + (\frac{1}{2})\mathbf{v}$. In other words, the $\mathbf{UV}$ (plane) coordinates of intersection point $\mathbf{P}$ are $(1,\frac{1}{2})$.

Generally, given some arbitrary point $\mathbf{P}$, we seek two scalar values $\alpha$ and $\beta$, so that

$$ \mathbf{P} = \mathbf{Q} + \alpha \mathbf{u} + \beta \mathbf{v} $$

If $\mathbf{u}$ and $\mathbf{v}$ were guaranteed to be orthogonal to each other (forming a 90° angle between them), then this would be a simple matter of using the dot product to project $\mathbf{P}$ onto each of the basis vectors $\mathbf{u}$ and $\mathbf{v}$. However, since we are not restricting $\mathbf{u}$ and $\mathbf{v}$ to be orthogonal, the math's a little bit trickier.

$$ \mathbf{P} = \mathbf{Q} + \alpha \mathbf{u} + \beta \mathbf{v}$$

$$ \mathbf{p} = \mathbf{P} - \mathbf{Q} = \alpha \mathbf{u} + \beta \mathbf{v} $$

Here, $\mathbf{P}$ is the point of intersection, and $\mathbf{p}$ is the vector from $\mathbf{Q}$ to $\mathbf{P}$.

Cross the above equation with $\mathbf{u}$ and $\mathbf{v}$, respectively:

$$ \begin{align} \mathbf{u} \times \mathbf{p} &= \mathbf{u} \times (\alpha \mathbf{u} + \beta \mathbf{v}) \ &= \mathbf{u} \times \alpha \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{u} \times \beta \mathbf{v} \ &= \alpha(\mathbf{u} \times \mathbf{u}) + \beta(\mathbf{u} \times \mathbf{v}) \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \mathbf{v} \times \mathbf{p} &= \mathbf{v} \times (\alpha \mathbf{u} + \beta \mathbf{v}) \ &= \mathbf{v} \times \alpha \mathbf{u} + \mathbf{v} \times \beta \mathbf{v} \ &= \alpha(\mathbf{v} \times \mathbf{u}) + \beta(\mathbf{v} \times \mathbf{v}) \end{align} $$

Since any vector crossed with itself yields zero, these equations simplify to

$$ \mathbf{v} \times \mathbf{p} = \alpha(\mathbf{v} \times \mathbf{u}) $$ $$ \mathbf{u} \times \mathbf{p} = \beta(\mathbf{u} \times \mathbf{v}) $$

Now to solve for the coefficients $\alpha$ and $\beta$. If you're new to vector math, you might try to divide by $\mathbf{u} \times \mathbf{v}$ and $\mathbf{v} \times \mathbf{u}$, but you can't divide by vectors. Instead, we can take the dot product of both sides of the above equations with the plane normal $\mathbf{n} = \mathbf{u} \times \mathbf{v}$, reducing both sides to scalars, which we can divide by.

$$ \mathbf{n} \cdot (\mathbf{v} \times \mathbf{p}) = \mathbf{n} \cdot \alpha(\mathbf{v} \times \mathbf{u}) $$

$$ \mathbf{n} \cdot (\mathbf{u} \times \mathbf{p}) = \mathbf{n} \cdot \beta(\mathbf{u} \times \mathbf{v}) $$

Now isolating the coefficients is a simple matter of division:

$$ \alpha = \frac{\mathbf{n} \cdot (\mathbf{v} \times \mathbf{p})} {\mathbf{n} \cdot (\mathbf{v} \times \mathbf{u})} $$

$$ \beta = \frac{\mathbf{n} \cdot (\mathbf{u} \times \mathbf{p})} {\mathbf{n} \cdot (\mathbf{u} \times \mathbf{v})} $$

Reversing the cross products for both the numerator and denominator of $\alpha$ (recall that $\mathbf{a} \times \mathbf{b} = - \mathbf{b} \times \mathbf{a}$) gives us a common denominator for both coefficients:

$$ \alpha = \frac{\mathbf{n} \cdot (\mathbf{p} \times \mathbf{v})} {\mathbf{n} \cdot (\mathbf{u} \times \mathbf{v})} $$

$$ \beta = \frac{\mathbf{n} \cdot (\mathbf{u} \times \mathbf{p})} {\mathbf{n} \cdot (\mathbf{u} \times \mathbf{v})} $$

Now we can perform one final simplification, computing a vector $\mathbf{w}$ that will be constant for the plane's basis frame, for any planar point $\mathbf{P}$:

$$ \mathbf{w} = \frac{\mathbf{n}}{\mathbf{n} \cdot (\mathbf{u} \times \mathbf{v})} = \frac{\mathbf{n}}{\mathbf{n} \cdot \mathbf{n}}$$

$$ \alpha = \mathbf{w} \cdot (\mathbf{p} \times \mathbf{v}) $$ $$ \beta = \mathbf{w} \cdot (\mathbf{u} \times \mathbf{p}) $$

The vector $\mathbf{w}$ is constant for a given quadrilateral, so we'll cache that value.

class quad : public hittable {

public:

quad(const point3& _Q, const vec3& _u, const vec3& _v, shared_ptr<material> m)

: Q(_Q), u(_u), v(_v), mat(m)

{

auto n = cross(u, v);

normal = unit_vector(n);

D = dot(normal, Q);

w = n / dot(n,n);

set_bounding_box();

}

...

private:

point3 Q;

vec3 u, v;

shared_ptr<material> mat;

aabb bbox;

vec3 normal;

double D;

vec3 w;

};

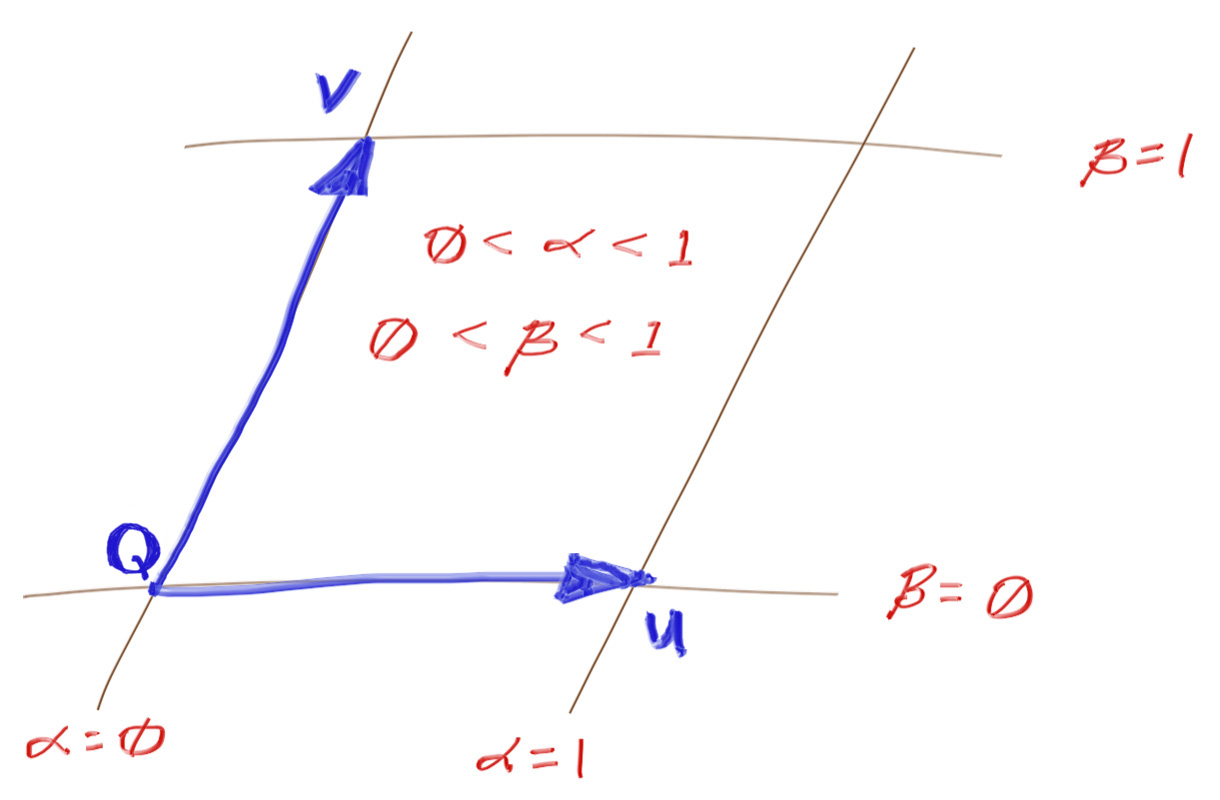

Interior Testing of The Intersection Using UV Coordinates

Now that we have the intersection point's planar coordinates $\alpha$ and $\beta$, we can easily use these to determine if the intersection point is inside the quadrilateral -- that is, if the ray actually hit the quadrilateral.

The plane is divided into coordinate regions like so:

Thus, to see if a point with planar coordinates $(\alpha,\beta)$ lies inside the quadrilateral, it just needs to meet the following criteria:

- $ 0 \leq \alpha \leq 1 $

- $ 0 \leq \beta \leq 1 $

That's the last piece needed to implement quadrilateral primitives.

Pause a bit here and consider that if you use the $(\alpha,\beta)$ coordinates to determine if a point lies inside a quadrilateral (parallelogram), it's not too hard to imagine using these same 2D coordinates to determine if the intersection point lies inside any other 2D (planar) primitive!

We'll leave these additional 2D shape possibilities as an exercise to the reader, depending on your desire to explore. Consider triangles, disks, and rings (all of these are surprisingly easy). You could even create cut-out stencils based on the pixels of a texture map, or a Mandelbrot shape!

In order to make such experimentation a bit easier, we'll factor out the $(\alpha,\beta)$ interior test method from the hit method.

...

#include <cmath>

class quad : public hittable {

public:

...

bool hit(const ray& r, interval ray_t, hit_record& rec) const override {

auto denom = dot(normal, r.direction());

// No hit if the ray is parallel to the plane.

if (fabs(denom) < 1e-8)

return false;

// Return false if the hit point parameter t is outside the ray interval.

auto t = (D - dot(normal, r.origin())) / denom;

if (!ray_t.contains(t))

return false;

// Determine the hit point lies within the planar shape using its plane coordinates.

auto intersection = r.at(t);

vec3 planar_hitpt_vector = intersection - Q;

auto alpha = dot(w, cross(planar_hitpt_vector, v));

auto beta = dot(w, cross(u, planar_hitpt_vector));

if (!is_interior(alpha, beta, rec))

return false;

// Ray hits the 2D shape; set the rest of the hit record and return true.

rec.t = t;

rec.p = intersection;

rec.mat = mat;

rec.set_face_normal(r, normal);

return true;

}

virtual bool is_interior(double a, double b, hit_record& rec) const {

// Given the hit point in plane coordinates, return false if it is outside the

// primitive, otherwise set the hit record UV coordinates and return true.

if ((a < 0) || (1 < a) || (b < 0) || (1 < b))

return false;

rec.u = a;

rec.v = b;

return true;

}

...

};

#endif

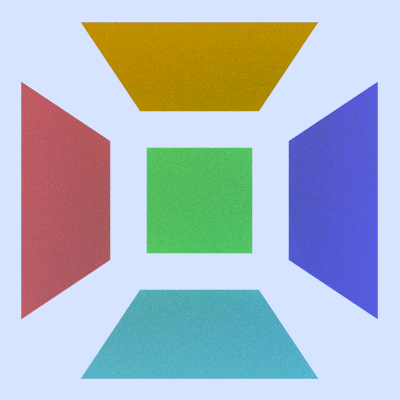

And now we add a new scene to demonstrate our new quad primitive:

...

#include "quad.h"

...

void quads() {

hittable_list world;

// Materials

auto left_red = make_shared<lambertian>(color(1.0, 0.2, 0.2));

auto back_green = make_shared<lambertian>(color(0.2, 1.0, 0.2));

auto right_blue = make_shared<lambertian>(color(0.2, 0.2, 1.0));

auto upper_orange = make_shared<lambertian>(color(1.0, 0.5, 0.0));

auto lower_teal = make_shared<lambertian>(color(0.2, 0.8, 0.8));

// Quads

world.add(make_shared<quad>(point3(-3,-2, 5), vec3(0, 0,-4), vec3(0, 4, 0), left_red));

world.add(make_shared<quad>(point3(-2,-2, 0), vec3(4, 0, 0), vec3(0, 4, 0), back_green));

world.add(make_shared<quad>(point3( 3,-2, 1), vec3(0, 0, 4), vec3(0, 4, 0), right_blue));

world.add(make_shared<quad>(point3(-2, 3, 1), vec3(4, 0, 0), vec3(0, 0, 4), upper_orange));

world.add(make_shared<quad>(point3(-2,-3, 5), vec3(4, 0, 0), vec3(0, 0,-4), lower_teal));

camera cam;

cam.aspect_ratio = 1.0;

cam.image_width = 400;

cam.samples_per_pixel = 100;

cam.max_depth = 50;

cam.vfov = 80;

cam.lookfrom = point3(0,0,9);

cam.lookat = point3(0,0,0);

cam.vup = vec3(0,1,0);

cam.defocus_angle = 0;

cam.render(world);

}

int main() {

switch (5) {

case 1: random_spheres(); break;

case 2: two_spheres(); break;

case 3: earth(); break;

case 4: two_perlin_spheres(); break;

case 5: quads(); break;

}

}