Perlin Noise

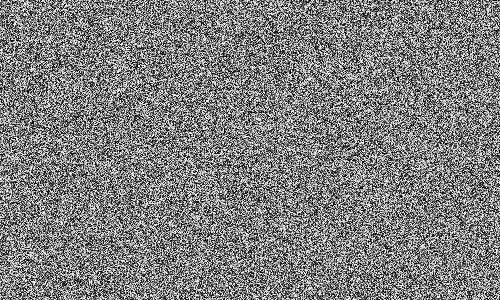

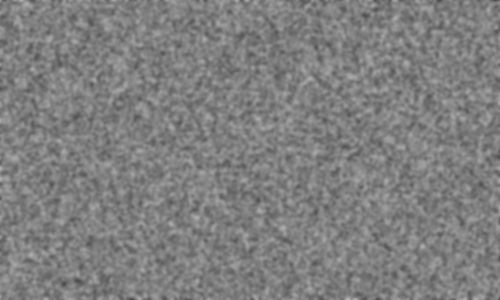

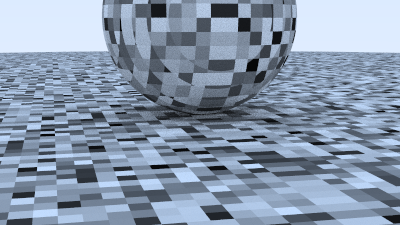

To get cool looking solid textures most people use some form of Perlin noise. These are named after their inventor Ken Perlin. Perlin texture doesn’t return white noise like this:

Instead it returns something similar to blurred white noise:

A key part of Perlin noise is that it is repeatable: it takes a 3D point as input and always returns the same randomish number. Nearby points return similar numbers. Another important part of Perlin noise is that it be simple and fast, so it’s usually done as a hack. I’ll build that hack up incrementally based on Andrew Kensler’s description.

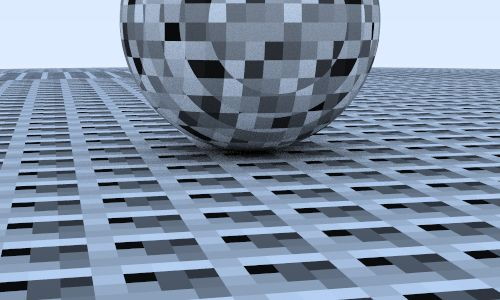

Using Blocks of Random Numbers

We could just tile all of space with a 3D array of random numbers and use them in blocks. You get something blocky where the repeating is clear:

Let’s just use some sort of hashing to scramble this, instead of tiling. This has a bit of support code to make it all happen:

#ifndef PERLIN_H

#define PERLIN_H

#include "rtweekend.h"

class perlin {

public:

perlin() {

ranfloat = new double[point_count];

for (int i = 0; i < point_count; ++i) {

ranfloat[i] = random_double();

}

perm_x = perlin_generate_perm();

perm_y = perlin_generate_perm();

perm_z = perlin_generate_perm();

}

~perlin() {

delete[] ranfloat;

delete[] perm_x;

delete[] perm_y;

delete[] perm_z;

}

double noise(const point3& p) const {

auto i = static_cast<int>(4*p.x()) & 255;

auto j = static_cast<int>(4*p.y()) & 255;

auto k = static_cast<int>(4*p.z()) & 255;

return ranfloat[perm_x[i] ^ perm_y[j] ^ perm_z[k]];

}

private:

static const int point_count = 256;

double* ranfloat;

int* perm_x;

int* perm_y;

int* perm_z;

static int* perlin_generate_perm() {

auto p = new int[point_count];

for (int i = 0; i < perlin::point_count; i++)

p[i] = i;

permute(p, point_count);

return p;

}

static void permute(int* p, int n) {

for (int i = n-1; i > 0; i--) {

int target = random_int(0, i);

int tmp = p[i];

p[i] = p[target];

p[target] = tmp;

}

}

};

#endif

Now if we create an actual texture that takes these floats between 0 and 1 and creates grey colors:

#include "perlin.h"

class noise_texture : public texture {

public:

noise_texture() {}

color value(double u, double v, const point3& p) const override {

return color(1,1,1) * noise.noise(p);

}

private:

perlin noise;

};

We can use that texture on some spheres:

void two_perlin_spheres() {

hittable_list world;

auto pertext = make_shared<noise_texture>();

world.add(make_shared<sphere>(point3(0,-1000,0), 1000, make_shared<lambertian>(pertext)));

world.add(make_shared<sphere>(point3(0,2,0), 2, make_shared<lambertian>(pertext)));

camera cam;

cam.aspect_ratio = 16.0 / 9.0;

cam.image_width = 400;

cam.samples_per_pixel = 100;

cam.max_depth = 50;

cam.vfov = 20;

cam.lookfrom = point3(13,2,3);

cam.lookat = point3(0,0,0);

cam.vup = vec3(0,1,0);

cam.defocus_angle = 0;

cam.render(world);

}

int main() {

switch (4) {

case 1: random_spheres(); break;

case 2: two_spheres(); break;

case 3: earth(); break;

case 4: two_perlin_spheres(); break;

}

}

Add the hashing does scramble as hoped:

Smoothing out the Result

To make it smooth, we can linearly interpolate:

class perlin {

public:

...

double noise(const point3& p) const {

auto u = p.x() - floor(p.x());

auto v = p.y() - floor(p.y());

auto w = p.z() - floor(p.z());

auto i = static_cast<int>(floor(p.x()));

auto j = static_cast<int>(floor(p.y()));

auto k = static_cast<int>(floor(p.z()));

double c[2][2][2];

for (int di=0; di < 2; di++)

for (int dj=0; dj < 2; dj++)

for (int dk=0; dk < 2; dk++)

c[di][dj][dk] = ranfloat[

perm_x[(i+di) & 255] ^

perm_y[(j+dj) & 255] ^

perm_z[(k+dk) & 255]

];

return trilinear_interp(c, u, v, w);

}

...

private:

...

static double trilinear_interp(double c[2][2][2], double u, double v, double w) {

auto accum = 0.0;

for (int i=0; i < 2; i++)

for (int j=0; j < 2; j++)

for (int k=0; k < 2; k++)

accum += (i*u + (1-i)*(1-u))*

(j*v + (1-j)*(1-v))*

(k*w + (1-k)*(1-w))*c[i][j][k];

return accum;

}

};

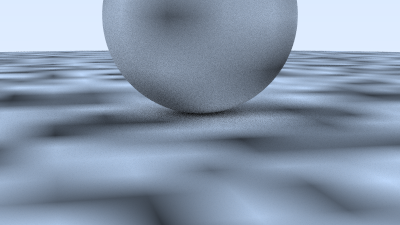

And we get:

Improvement with Hermitian Smoothing

Smoothing yields an improved result, but there are obvious grid features in there. Some of it is Mach bands, a known perceptual artifact of linear interpolation of color. A standard trick is to use a Hermite cubic to round off the interpolation:

class perlin (

public:

...

double noise(const point3& p) const {

auto u = p.x() - floor(p.x());

auto v = p.y() - floor(p.y());

auto w = p.z() - floor(p.z());

u = u*u*(3-2*u);

v = v*v*(3-2*v);

w = w*w*(3-2*w);

auto i = static_cast<int>(floor(p.x()));

auto j = static_cast<int>(floor(p.y()));

auto k = static_cast<int>(floor(p.z()));

...

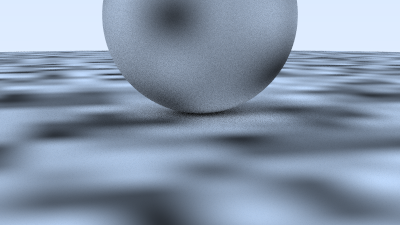

This gives a smoother looking image:

Tweaking The Frequency

It is also a bit low frequency. We can scale the input point to make it vary more quickly:

class noise_texture : public texture {

public:

noise_texture() {}

noise_texture(double sc) : scale(sc) {}

color value(double u, double v, const point3& p) const override {

return color(1,1,1) * noise.noise(scale * p);

}

private:

perlin noise;

double scale;

};

We then add that scale to the two_perlin_spheres() scene description:

void two_perlin_spheres() {

...

auto pertext = make_shared<noise_texture>(4);

world.add(make_shared<sphere>(point3(0,-1000,0), 1000, make_shared<lambertian>(pertext)));

world.add(make_shared<sphere>(point3(0, 2, 0), 2, make_shared<lambertian>(pertext)));

camera cam;

..

}

This yields the following result:

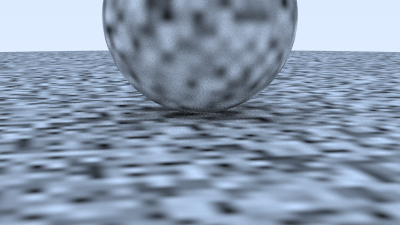

Using Random Vectors on the Lattice Points

This is still a bit blocky looking, probably because the min and max of the pattern always lands exactly on the integer x/y/z. Ken Perlin’s very clever trick was to instead put random unit vectors (instead of just floats) on the lattice points, and use a dot product to move the min and max off the lattice. So, first we need to change the random floats to random vectors. These vectors are any reasonable set of irregular directions, and I won't bother to make them exactly uniform:

class perlin {

public:

perlin() {

ranvec = new vec3[point_count];

for (int i = 0; i < point_count; ++i) {

ranvec[i] = unit_vector(vec3::random(-1,1));

}

perm_x = perlin_generate_perm();

perm_y = perlin_generate_perm();

perm_z = perlin_generate_perm();

}

~perlin() {

delete[] ranvec;

delete[] perm_x;

delete[] perm_y;

delete[] perm_z;

}

...

private:

static const int point_count = 256;

vec3* ranvec;

int* perm_x;

int* perm_y;

int* perm_z;

...

};

The Perlin class noise() method is now:

class perlin {

public:

...

double noise(const point3& p) const {

auto u = p.x() - floor(p.x());

auto v = p.y() - floor(p.y());

auto w = p.z() - floor(p.z());

auto i = static_cast<int>(floor(p.x()));

auto j = static_cast<int>(floor(p.y()));

auto k = static_cast<int>(floor(p.z()));

vec3 c[2][2][2];

for (int di=0; di < 2; di++)

for (int dj=0; dj < 2; dj++)

for (int dk=0; dk < 2; dk++)

c[di][dj][dk] = ranvec[

perm_x[(i+di) & 255] ^

perm_y[(j+dj) & 255] ^

perm_z[(k+dk) & 255]

];

return perlin_interp(c, u, v, w);

}

...

};

And the interpolation becomes a bit more complicated:

class perlin {

...

private:

...

static double perlin_interp(vec3 c[2][2][2], double u, double v, double w) {

auto uu = u*u*(3-2*u);

auto vv = v*v*(3-2*v);

auto ww = w*w*(3-2*w);

auto accum = 0.0;

for (int i=0; i < 2; i++)

for (int j=0; j < 2; j++)

for (int k=0; k < 2; k++) {

vec3 weight_v(u-i, v-j, w-k);

accum += (i*uu + (1-i)*(1-uu))

* (j*vv + (1-j)*(1-vv))

* (k*ww + (1-k)*(1-ww))

* dot(c[i][j][k], weight_v);

}

return accum;

}

...

};

The output of the perlin interpretation can return negative values. These negative values will be

passed to the sqrt() function of our gamma function and get turned into NaNs. We will cast the

perlin output back to between 0 and 1.

class noise_texture : public texture {

public:

noise_texture() {}

noise_texture(double sc) : scale(sc) {}

color value(double u, double v, const point3& p) const override {

return color(1,1,1) * 0.5 * (1.0 + noise.noise(scale * p));

}

private:

perlin noise;

double scale;

};

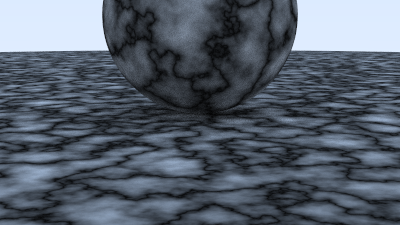

This finally gives something more reasonable looking:

Introducing Turbulence

Very often, a composite noise that has multiple summed frequencies is used. This is usually called turbulence, and is a sum of repeated calls to noise:

class perlin {

...

public:

...

double turb(const point3& p, int depth=7) const {

auto accum = 0.0;

auto temp_p = p;

auto weight = 1.0;

for (int i = 0; i < depth; i++) {

accum += weight*noise(temp_p);

weight *= 0.5;

temp_p *= 2;

}

return fabs(accum);

}

...

Here fabs() is the absolute value function defined in <cmath>.

class noise_texture : public texture {

public:

noise_texture() {}

noise_texture(double sc) : scale(sc) {}

color value(double u, double v, const point3& p) const override {

auto s = scale * p;

return color(1,1,1) * noise.turb(s);

}

private:

perlin noise;

double scale;

};

Used directly, turbulence gives a sort of camouflage netting appearance:

Adjusting the Phase

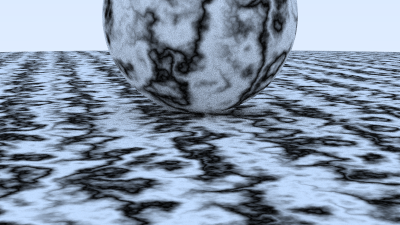

However, usually turbulence is used indirectly. For example, the “hello world” of procedural solid textures is a simple marble-like texture. The basic idea is to make color proportional to something like a sine function, and use turbulence to adjust the phase (so it shifts $x$ in $\sin(x)$) which makes the stripes undulate. Commenting out straight noise and turbulence, and giving a marble-like effect is:

class noise_texture : public texture {

public:

noise_texture() {}

noise_texture(double sc) : scale(sc) {}

color value(double u, double v, const point3& p) const override {

auto s = scale * p;

return color(1,1,1) * 0.5 * (1 + sin(s.z() + 10*noise.turb(s)));

}

private:

perlin noise;

double scale;

};

Which yields: