Motion Blur

When you decided to ray trace, you decided that visual quality was worth more than run-time. When rendering fuzzy reflection and defocus blur, we used multiple samples per pixel. Once you have taken a step down that road, the good news is that almost all effects can be similarly brute-forced. Motion blur is certainly one of those.

In a real camera, the shutter remains open for a short time interval, during which the camera and objects in the world may move. To accurately reproduce such a camera shot, we seek an average of what the camera senses while its shutter is open to the world.

Introduction of SpaceTime Ray Tracing

We can get a random estimate of a single (simplified) photon by sending a single ray at some random instant in time while the shutter is open. As long as we can determine where the objects are supposed to be at that instant, we can get an accurate measure of the light for that ray at that same instant. This is yet another example of how random (Monte Carlo) ray tracing ends up being quite simple. Brute force wins again!

Since the “engine” of the ray tracer can just make sure the objects are where they need to be for each ray, the intersection guts don’t change much. To accomplish this, we need to store the exact time for each ray:

class ray {

public:

ray() {}

ray(const point3& origin, const vec3& direction) : orig(origin), dir(direction), tm(0)

{}

ray(const point3& origin, const vec3& direction, double time = 0.0)

: orig(origin), dir(direction), tm(time)

{}

point3 origin() const { return orig; }

vec3 direction() const { return dir; }

double time() const { return tm; }

point3 at(double t) const {

return orig + t*dir;

}

private:

point3 orig;

vec3 dir;

double tm;

};

Managing Time

Before continuing, let's think about time, and how we might manage it across one or more successive renders. There are two aspects of shutter timing to think about: the time from one shutter opening to the next shutter opening, and how long the shutter stays open for each frame. Standard movie film used to be shot at 24 frames per second. Modern digital movies can be 24, 30, 48, 60, 120 or however many frames per second director wants.

Each frame can have its own shutter speed. This shutter speed need not be -- and typically isn't -- the maximum duration of the entire frame. You could have the shutter open for 1/1000th of a second every frame, or 1/60th of a second.

If you wanted to render a sequence of images, you would need to set up the camera with the

appropriate shutter timings: frame-to-frame period, shutter/render duration, and the total number of

frames (total shot time). If the camera is moving and the world is static, you're good to go.

However, if anything in the world is moving, you would need to add a method to hittable so that

every object could be made aware of the current frame's time period. This method would provide a way

for all animated objects to set up their motion during that frame.

This is fairly straight-forward, and definitely a fun avenue for you to experiment with if you wish. However, for our purposes right now, we're going to proceed with a much simpler model. We will render only a single frame, implicitly assuming a start at time = 0 and ending at time = 1. Our first task is to modify the camera to launch rays with random times in $[0,1]$, and our second task will be the creation of an animated sphere class.

Updating the Camera to Simulate Motion Blur

We need to modify the camera to generate rays at a random instant between the start time and the end time. Should the camera keep track of the time interval, or should that be up to the user of the camera when a ray is created? When in doubt, I like to make constructors complicated if it makes calls simple, so I will make the camera keep track, but that’s a personal preference. Not many changes are needed to camera because for now it is not allowed to move; it just sends out rays over a time period.

class camera {

...

private:

...

ray get_ray(int i, int j) const {

// Get a randomly-sampled camera ray for the pixel at location i,j, originating from

// the camera defocus disk.

auto pixel_center = pixel00_loc + (i * pixel_delta_u) + (j * pixel_delta_v);

auto pixel_sample = pixel_center + pixel_sample_square();

auto ray_origin = (defocus_angle <= 0) ? center : defocus_disk_sample();

auto ray_direction = pixel_sample - ray_origin;

auto ray_time = random_double();

return ray(ray_origin, ray_direction, ray_time);

}

...

};

Adding Moving Spheres

Now to create a moving object.

I’ll update the sphere class so that its center moves linearly from center1 at time=0 to center2

at time=1.

(It continues on indefinitely outside that time interval, so it really can be sampled at any time.)

class sphere : public hittable {

public:

// Stationary Sphere

sphere(point3 _center, double _radius, shared_ptr<material> _material)

: center1(_center), radius(_radius), mat(_material), is_moving(false) {}

// Moving Sphere

sphere(point3 _center1, point3 _center2, double _radius, shared_ptr<material> _material)

: center1(_center1), radius(_radius), mat(_material), is_moving(true)

{

center_vec = _center2 - _center1;

}

...

private:

point3 center1;

double radius;

shared_ptr<material> mat;

bool is_moving;

vec3 center_vec;

point3 center(double time) const {

// Linearly interpolate from center1 to center2 according to time, where t=0 yields

// center1, and t=1 yields center2.

return center0 + time*center_vec;

}

};

#endif

An alternative to making special stationary spheres is to just make them all move, but stationary spheres have the same begin and end position. I’m on the fence about that trade-off between simpler code and more efficient stationary spheres, so let your design taste guide you.

The updated sphere::hit() function is almost identical to the old sphere::hit() function:

center just needs to query a function sphere_center(time):

class sphere : public hittable {

public:

...

bool hit(const ray& r, interval ray_t, hit_record& rec) const override {

point3 center = is_moving ? sphere_center(r.time()) : center1;

vec3 oc = r.origin() - center;

auto a = r.direction().length_squared();

auto half_b = dot(oc, r.direction());

auto c = oc.length_squared() - radius*radius;

...

}

...

};

We need to implement the new interval::contains() method mentioned above:

class interval {

public:

...

bool contains(double x) const {

return min <= x && x <= max;

}

...

};

Tracking the Time of Ray Intersection

Now that rays have a time property, we need to update the material::scatter() methods to account

for the time of intersection:

class lambertian : public material {

...

bool scatter(const ray& r_in, const hit_record& rec, color& attenuation, ray& scattered)

const override {

auto scatter_direction = rec.normal + random_unit_vector();

// Catch degenerate scatter direction

if (scatter_direction.near_zero())

scatter_direction = rec.normal;

scattered = ray(rec.p, scatter_direction, r_in.time());

attenuation = albedo;

return true;

}

...

};

class metal : public material {

...

bool scatter(const ray& r_in, const hit_record& rec, color& attenuation, ray& scattered)

const override {

vec3 reflected = reflect(unit_vector(r_in.direction()), rec.normal);

scattered = ray(rec.p, reflected + fuzz*random_in_unit_sphere(), r_in.time());

attenuation = albedo;

return (dot(scattered.direction(), rec.normal) > 0);

}

...

};

class dielectric : public material {

...

bool scatter(const ray& r_in, const hit_record& rec, color& attenuation, ray& scattered)

const override {

...

scattered = ray(rec.p, direction, r_in.time());

return true;

}

...

};

Putting Everything Together

The code below takes the example diffuse spheres from the scene at the end of the last book, and makes them move during the image render. Each sphere moves from its center $\mathbf{C}$ at time $t=0$ to $\mathbf{C} + (0, r/2, 0)$ at time $t=1$:

int main() {

hittable_list world;

auto ground_material = make_shared<lambertian>(color(0.5, 0.5, 0.5));

world.add(make_shared<sphere>(point3(0,-1000,0), 1000, ground_material));

for (int a = -11; a < 11; a++) {

for (int b = -11; b < 11; b++) {

auto choose_mat = random_double();

point3 center(a + 0.9*random_double(), 0.2, b + 0.9*random_double());

if ((center - point3(4, 0.2, 0)).length() > 0.9) {

shared_ptr<material> sphere_material;

if (choose_mat < 0.8) {

// diffuse

auto albedo = color::random() * color::random();

sphere_material = make_shared<lambertian>(albedo);

auto center2 = center + vec3(0, random_double(0,.5), 0);

world.add(make_shared<sphere>(center, center2, 0.2, sphere_material));

} else if (choose_mat < 0.95) {

...

}

...

camera cam;

cam.aspect_ratio = 16.0 / 9.0;

cam.image_width = 400;

cam.samples_per_pixel = 100;

cam.max_depth = 50;

cam.vfov = 20;

cam.lookfrom = point3(13,2,3);

cam.lookat = point3(0,0,0);

cam.vup = vec3(0,1,0);

cam.defocus_angle = 0.02;

cam.focus_dist = 10.0;

cam.render(world);

}

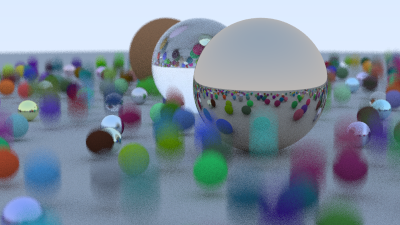

This gives the following result: