Instances

The Cornell Box usually has two blocks in it. These are rotated relative to the walls. First, let’s

create a function that returns a box, by creating a hittable_list of six rectangles:

...

#include "hittable_list.h"

...

inline shared_ptr<hittable_list> box(const point3& a, const point3& b, shared_ptr<material> mat)

{

// Returns the 3D box (six sides) that contains the two opposite vertices a & b.

auto sides = make_shared<hittable_list>();

// Construct the two opposite vertices with the minimum and maximum coordinates.

auto min = point3(fmin(a.x(), b.x()), fmin(a.y(), b.y()), fmin(a.z(), b.z()));

auto max = point3(fmax(a.x(), b.x()), fmax(a.y(), b.y()), fmax(a.z(), b.z()));

auto dx = vec3(max.x() - min.x(), 0, 0);

auto dy = vec3(0, max.y() - min.y(), 0);

auto dz = vec3(0, 0, max.z() - min.z());

sides->add(make_shared<quad>(point3(min.x(), min.y(), max.z()), dx, dy, mat)); // front

sides->add(make_shared<quad>(point3(max.x(), min.y(), max.z()), -dz, dy, mat)); // right

sides->add(make_shared<quad>(point3(max.x(), min.y(), min.z()), -dx, dy, mat)); // back

sides->add(make_shared<quad>(point3(min.x(), min.y(), min.z()), dz, dy, mat)); // left

sides->add(make_shared<quad>(point3(min.x(), max.y(), max.z()), dx, -dz, mat)); // top

sides->add(make_shared<quad>(point3(min.x(), min.y(), min.z()), dx, dz, mat)); // bottom

return sides;

}

Now we can add two blocks (but not rotated).

void cornell_box() {

...

world.add(make_shared<quad>(point3(555,0,0), vec3(0,555,0), vec3(0,0,555), green));

world.add(make_shared<quad>(point3(0,0,0), vec3(0,555,0), vec3(0,0,555), red));

world.add(make_shared<quad>(point3(343, 554, 332), vec3(-130,0,0), vec3(0,0,-105), light));

world.add(make_shared<quad>(point3(0,0,0), vec3(555,0,0), vec3(0,0,555), white));

world.add(make_shared<quad>(point3(555,555,555), vec3(-555,0,0), vec3(0,0,-555), white));

world.add(make_shared<quad>(point3(0,0,555), vec3(555,0,0), vec3(0,555,0), white));

world.add(box(point3(130, 0, 65), point3(295, 165, 230), white));

world.add(box(point3(265, 0, 295), point3(430, 330, 460), white));

camera cam;

...

}

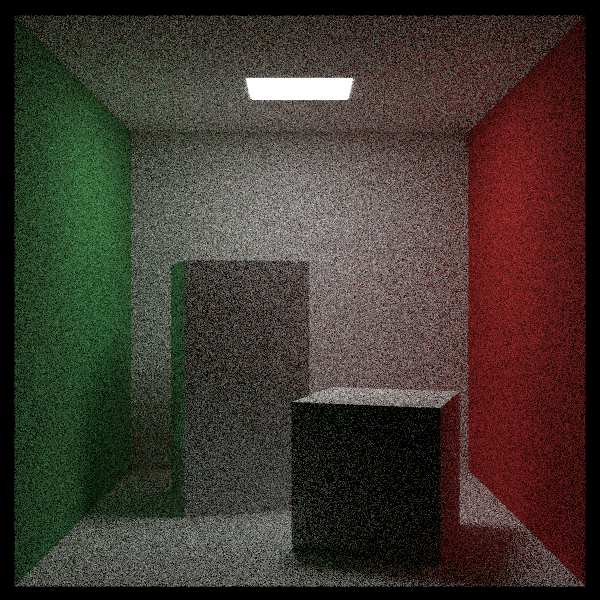

This gives:

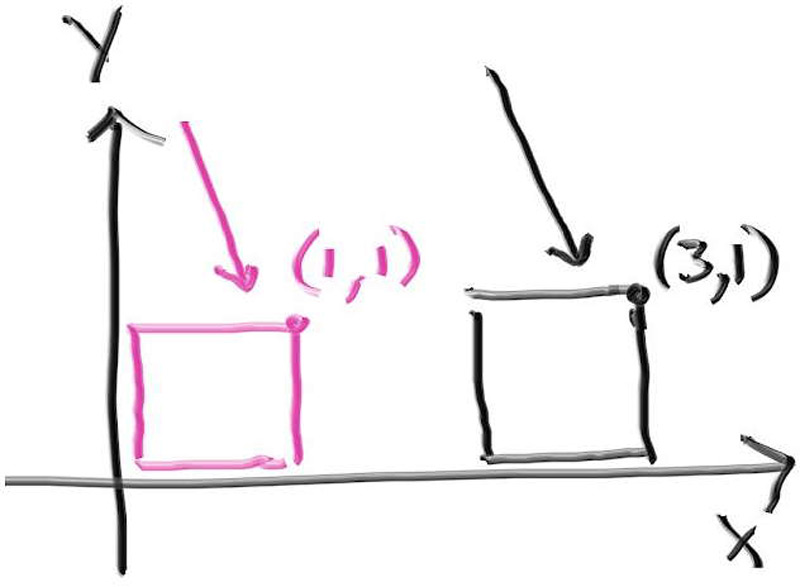

Now that we have boxes, we need to rotate them a bit to have them match the real Cornell box. In

ray tracing, this is usually done with an instance. An instance is a copy of a geometric

primitive that has been placed into the scene. This instance is entirely independent of the other

copies of the primitive and can be moved or rotated. In this case, our geometric primitive is our

hittable box object, and we want to rotate it. This is especially easy in ray tracing because we

don’t actually need to move objects in the scene; instead we move the rays in the opposite

direction. For example, consider a translation (often called a move). We could take the pink box

at the origin and add two to all its x components, or (as we almost always do in ray tracing) leave

the box where it is, but in its hit routine subtract two off the x-component of the ray origin.

Instance Translation

Whether you think of this as a move or a change of coordinates is up to you. The way to reason about this is to think of moving the incident ray backwards the offset amount, determining if an intersection occurs, and then moving that intersection point forward the offset amount.

We need to move the intersection point forward the offset amount so that the intersection is actually in the path of the incident ray. If we forgot to move the intersection point forward then the intersection would be in the path of the offset ray, which isn't correct. Let's add the code to make this happen.

class translate : public hittable {

public:

bool hit(const ray& r, interval ray_t, hit_record& rec) const override {

// Move the ray backwards by the offset

ray offset_r(r.origin() - offset, r.direction(), r.time());

// Determine where (if any) an intersection occurs along the offset ray

if (!object->hit(offset_r, ray_t, rec))

return false;

// Move the intersection point forwards by the offset

rec.p += offset;

return true;

}

private:

shared_ptr<hittable> object;

vec3 offset;

};

... and then flesh out the rest of the translate class:

class translate : public hittable {

public:

translate(shared_ptr<hittable> p, const vec3& displacement)

: object(p), offset(displacement)

{

bbox = object->bounding_box() + offset;

}

bool hit(const ray& r, interval ray_t, hit_record& rec) const override {

// Move the ray backwards by the offset

ray offset_r(r.origin() - offset, r.direction(), r.time());

// Determine where (if any) an intersection occurs along the offset ray

if (!object->hit(offset_r, ray_t, rec))

return false;

// Move the intersection point forwards by the offset

rec.p += offset;

return true;

}

aabb bounding_box() const override { return bbox; }

private:

shared_ptr<hittable> object;

vec3 offset;

aabb bbox;

};

We also need to remember to offset the bounding box, otherwise the incident ray might be looking in

the wrong place and trivially reject the intersection.

The expression object->bounding_box() + offset above requires some additional support.

class aabb {

...

};

aabb operator+(const aabb& bbox, const vec3& offset) {

return aabb(bbox.x + offset.x(), bbox.y + offset.y(), bbox.z + offset.z());

}

aabb operator+(const vec3& offset, const aabb& bbox) {

return bbox + offset;

}

Since each dimension of an aabb is represented as an interval, we'll need to extend interval

with an addition operator as well.

class interval {

...

};

const interval interval::empty = interval(+infinity, -infinity);

const interval interval::universe = interval(-infinity, +infinity);

interval operator+(const interval& ival, double displacement) {

return interval(ival.min + displacement, ival.max + displacement);

}

interval operator+(double displacement, const interval& ival) {

return ival + displacement;

}

Instance Rotation

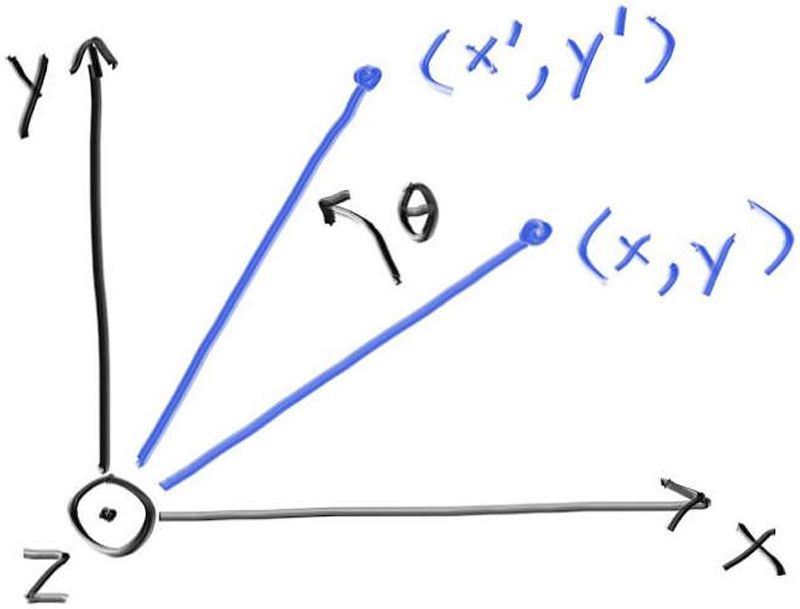

Rotation isn’t quite as easy to understand or generate the formulas for. A common graphics tactic is to apply all rotations about the x, y, and z axes. These rotations are in some sense axis-aligned. First, let’s rotate by theta about the z-axis. That will be changing only x and y, and in ways that don’t depend on z.

This involves some basic trigonometry that uses formulas that I will not cover here. That gives you the correct impression it’s a little involved, but it is straightforward, and you can find it in any graphics text and in many lecture notes. The result for rotating counter-clockwise about z is:

$$ x' = \cos(\theta) \cdot x - \sin(\theta) \cdot y $$ $$ y' = \sin(\theta) \cdot x + \cos(\theta) \cdot y $$

The great thing is that it works for any $\theta$ and doesn’t need any cases for quadrants or anything like that. The inverse transform is the opposite geometric operation: rotate by $-\theta$. Here, recall that $\cos(\theta) = \cos(-\theta)$ and $\sin(-\theta) = -\sin(\theta)$, so the formulas are very simple.

Similarly, for rotating about y (as we want to do for the blocks in the box) the formulas are:

$$ x' = \cos(\theta) \cdot x + \sin(\theta) \cdot z $$ $$ z' = -\sin(\theta) \cdot x + \cos(\theta) \cdot z $$

And if we want to rotate about the x-axis:

$$ y' = \cos(\theta) \cdot y - \sin(\theta) \cdot z $$ $$ z' = \sin(\theta) \cdot y + \cos(\theta) \cdot z $$

Thinking of translation as a simple movement of the initial ray is a fine way to reason about what's going on. But, for a more complex operation like a rotation, it can be easy to accidentally get your terms crossed (or forget a negative sign), so it's better to consider a rotation as a change of coordinates.

The pseudocode for the translate::hit function above describes the function in terms of moving:

- Move the ray backwards by the offset

- Determine whether an intersection exists along the offset ray (and if so, where)

- Move the intersection point forwards by the offset

But this can also be thought of in terms of a changing of coordinates:

- Change the ray from world space to object space

- Determine whether an intersection exists in object space (and if so, where)

- Change the intersection point from object space to world space

Rotating an object will not only change the point of intersection, but will also change the surface normal vector, which will change the direction of reflections and refractions. So we need to change the normal as well. Fortunately, the normal will rotate similarly to a vector, so we can use the same formulas as above. While normals and vectors may appear identical for an object undergoing rotation and translation, an object undergoing scaling requires special attention to keep the normals orthogonal to the surface. We won't cover that here, but you should research surface normal transformations if you implement scaling.

We need to start by changing the ray from world space to object space, which for rotation means rotating by $-\theta$.

$$ x' = \cos(\theta) \cdot x - \sin(\theta) \cdot z $$ $$ z' = \sin(\theta) \cdot x + \cos(\theta) \cdot z $$

We can now create a class for y-rotation:

class rotate_y : public hittable {

public:

bool hit(const ray& r, interval ray_t, hit_record& rec) const override {

// Change the ray from world space to object space

auto origin = r.origin();

auto direction = r.direction();

origin[0] = cos_theta*r.origin()[0] - sin_theta*r.origin()[2];

origin[2] = sin_theta*r.origin()[0] + cos_theta*r.origin()[2];

direction[0] = cos_theta*r.direction()[0] - sin_theta*r.direction()[2];

direction[2] = sin_theta*r.direction()[0] + cos_theta*r.direction()[2];

ray rotated_r(origin, direction, r.time());

// Determine where (if any) an intersection occurs in object space

if (!object->hit(rotated_r, ray_t, rec))

return false;

// Change the intersection point from object space to world space

auto p = rec.p;

p[0] = cos_theta*rec.p[0] + sin_theta*rec.p[2];

p[2] = -sin_theta*rec.p[0] + cos_theta*rec.p[2];

// Change the normal from object space to world space

auto normal = rec.normal

normal[0] = cos_theta*rec.normal[0] + sin_theta*rec.normal[2];

normal[2] = -sin_theta*rec.normal[0] + cos_theta*rec.normal[2];

rec.p = p;

rec.normal = normal;

return true;

}

};

... and now for the rest of the class:

class rotate_y : public hittable {

public:

rotate_y(shared_ptr<hittable> p, double angle) : object(p) {

auto radians = degrees_to_radians(angle);

sin_theta = sin(radians);

cos_theta = cos(radians);

bbox = object->bounding_box();

point3 min( infinity, infinity, infinity);

point3 max(-infinity, -infinity, -infinity);

for (int i = 0; i < 2; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < 2; j++) {

for (int k = 0; k < 2; k++) {

auto x = i*bbox.x.max + (1-i)*bbox.x.min;

auto y = j*bbox.y.max + (1-j)*bbox.y.min;

auto z = k*bbox.z.max + (1-k)*bbox.z.min;

auto newx = cos_theta*x + sin_theta*z;

auto newz = -sin_theta*x + cos_theta*z;

vec3 tester(newx, y, newz);

for (int c = 0; c < 3; c++) {

min[c] = fmin(min[c], tester[c]);

max[c] = fmax(max[c], tester[c]);

}

}

}

}

bbox = aabb(min, max);

}

bool hit(const ray& r, interval ray_t, hit_record& rec) const override {

...

}

aabb bounding_box() const override { return bbox; }

private:

shared_ptr<hittable> object;

double sin_theta;

double cos_theta;

aabb bbox;

};

And the changes to Cornell are:

void cornell_box() {

...

world.add(make_shared<quad>(point3(0,0,555), vec3(555,0,0), vec3(0,555,0), white));

shared_ptr<hittable> box1 = box(point3(0,0,0), point3(165,330,165), white);

box1 = make_shared<rotate_y>(box1, 15);

box1 = make_shared<translate>(box1, vec3(265,0,295));

world.add(box1);

shared_ptr<hittable> box2 = box(point3(0,0,0), point3(165,165,165), white);

box2 = make_shared<rotate_y>(box2, -18);

box2 = make_shared<translate>(box2, vec3(130,0,65));

world.add(box2);

camera cam;

...

}

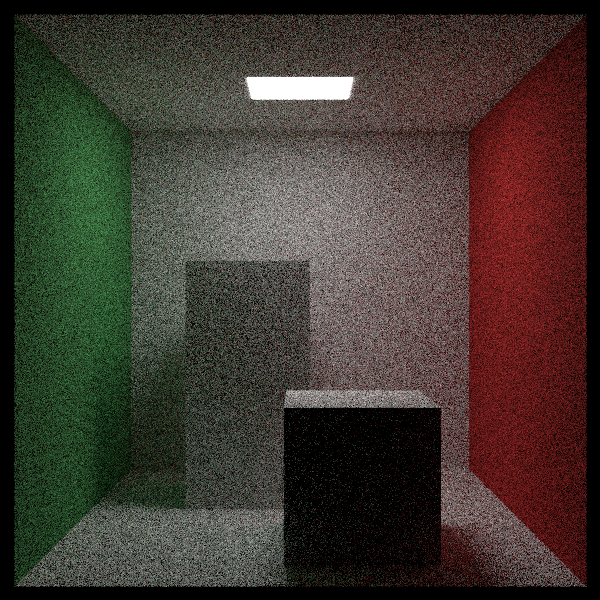

Which yields: