Bounding Volume Hierarchies

This part is by far the most difficult and involved part of the ray tracer we are working on. I am

sticking it in this chapter so the code can run faster, and because it refactors hittable a

little, and when I add rectangles and boxes we won't have to go back and refactor them.

The ray-object intersection is the main time-bottleneck in a ray tracer, and the time is linear with the number of objects. But it’s a repeated search on the same model, so we ought to be able to make it a logarithmic search in the spirit of binary search. Because we are sending millions to billions of rays on the same model, we can do an analog of sorting the model, and then each ray intersection can be a sublinear search. The two most common families of sorting are to 1) divide the space, and 2) divide the objects. The latter is usually much easier to code up and just as fast to run for most models.

The Key Idea

The key idea of a bounding volume over a set of primitives is to find a volume that fully encloses (bounds) all the objects. For example, suppose you computed a sphere that bounds 10 objects. Any ray that misses the bounding sphere definitely misses all ten objects inside. If the ray hits the bounding sphere, then it might hit one of the ten objects. So the bounding code is always of the form:

A key thing is we are dividing objects into subsets. We are not dividing the screen or the volume. Any object is in just one bounding volume, but bounding volumes can overlap.

Hierarchies of Bounding Volumes

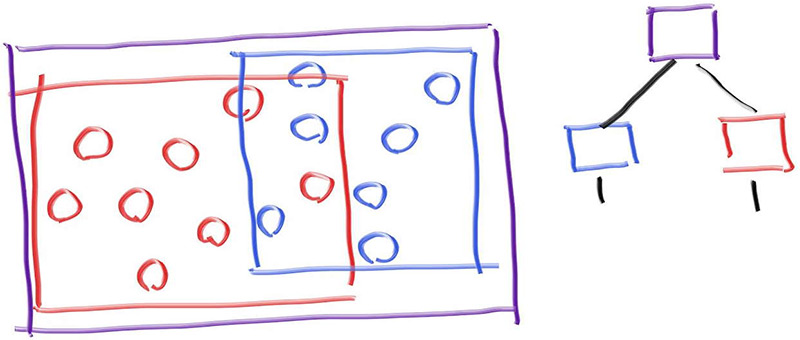

To make things sub-linear we need to make the bounding volumes hierarchical. For example, if we divided a set of objects into two groups, red and blue, and used rectangular bounding volumes, we’d have:

Note that the blue and red bounding volumes are contained in the purple one, but they might overlap, and they are not ordered -- they are just both inside. So the tree shown on the right has no concept of ordering in the left and right children; they are simply inside. The code would be:

if (hits purple)

hit0 = hits blue enclosed objects

hit1 = hits red enclosed objects

if (hit0 or hit1)

return true and info of closer hit

return false

Axis-Aligned Bounding Boxes (AABBs)

To get that all to work we need a way to make good divisions, rather than bad ones, and a way to intersect a ray with a bounding volume. A ray bounding volume intersection needs to be fast, and bounding volumes need to be pretty compact. In practice for most models, axis-aligned boxes work better than the alternatives, but this design choice is always something to keep in mind if you encounter unusual types of models.

From now on we will call axis-aligned bounding rectangular parallelepiped (really, that is what they need to be called if precise) axis-aligned bounding boxes, or AABBs. Any method you want to use to intersect a ray with an AABB is fine. And all we need to know is whether or not we hit it; we don’t need hit points or normals or any of the stuff we need to display the object.

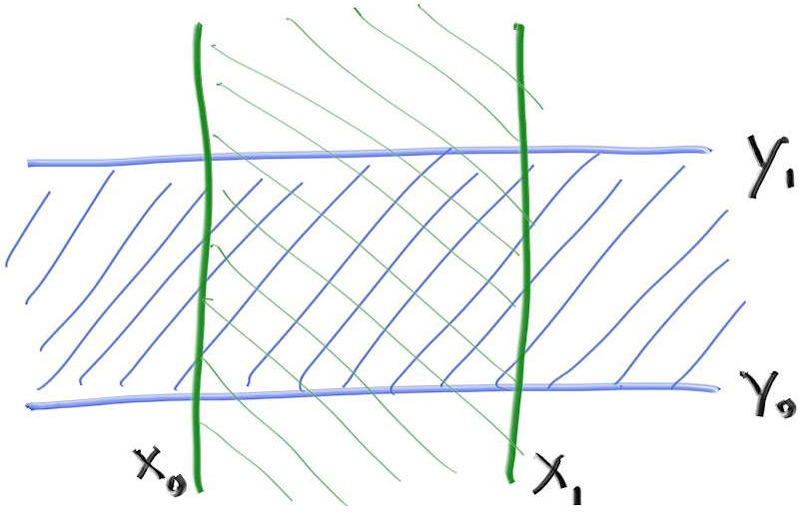

Most people use the “slab” method. This is based on the observation that an n-dimensional AABB is just the intersection of $n$ axis-aligned intervals, often called “slabs”. An interval is just the points between two endpoints, e.g., $x$ such that $3 < x < 5$, or more succinctly $x$ in $(3,5)$. In 2D, two intervals overlapping makes a 2D AABB (a rectangle):

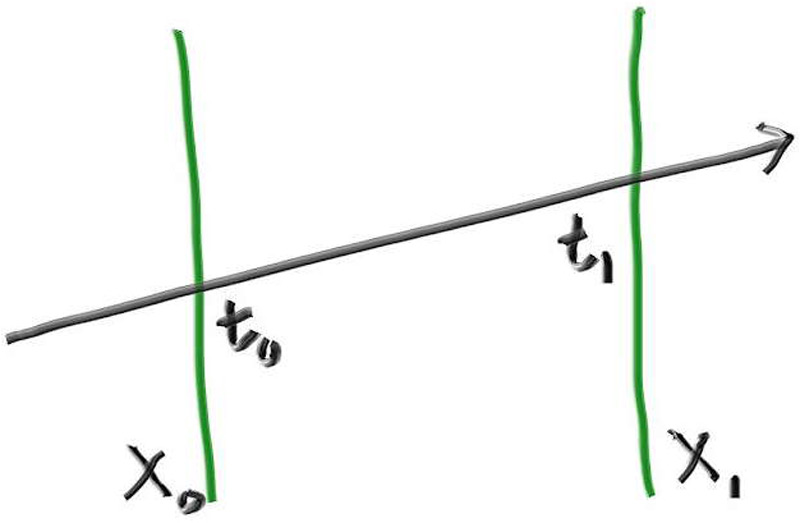

For a ray to hit one interval we first need to figure out whether the ray hits the boundaries. For example, again in 2D, this is the ray parameters $t_0$ and $t_1$. (If the ray is parallel to the plane, its intersection with the plane will be undefined.)

In 3D, those boundaries are planes. The equations for the planes are $x = x_0$ and $x = x_1$. Where does the ray hit that plane? Recall that the ray can be thought of as just a function that given a $t$ returns a location $\mathbf{P}(t)$:

$$ \mathbf{P}(t) = \mathbf{A} + t \mathbf{b} $$

This equation applies to all three of the x/y/z coordinates. For example, $x(t) = A_x + t b_x$. This ray hits the plane $x = x_0$ at the parameter $t$ that satisfies this equation:

$$ x_0 = A_x + t_0 b_x $$

Thus $t$ at that hitpoint is:

$$ t_0 = \frac{x_0 - A_x}{b_x} $$

We get the similar expression for $x_1$:

$$ t_1 = \frac{x_1 - A_x}{b_x} $$

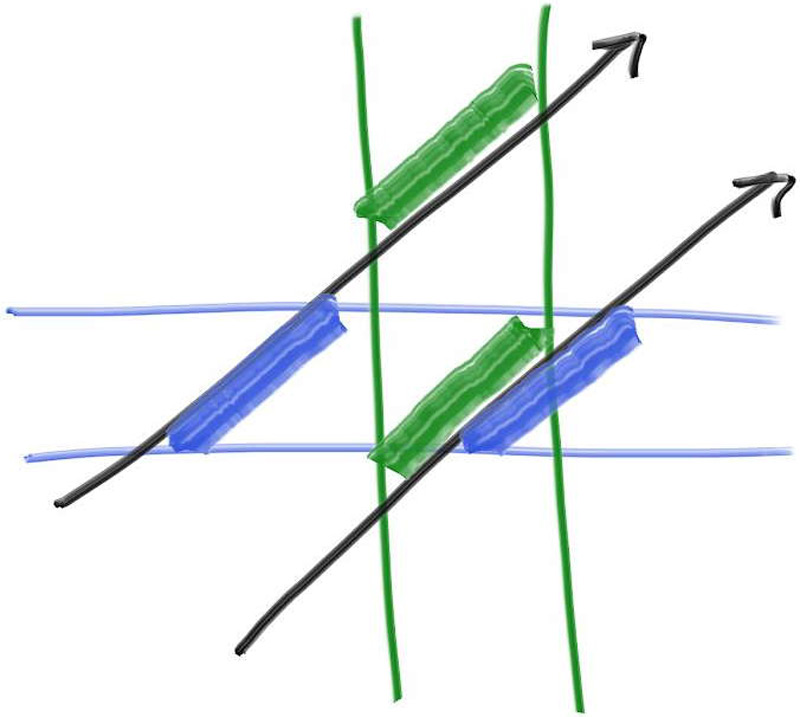

The key observation to turn that 1D math into a hit test is that for a hit, the $t$-intervals need to overlap. For example, in 2D the green and blue overlapping only happens if there is a hit:

Ray Intersection with an AABB

The following pseudocode determines whether the $t$ intervals in the slab overlap:

That is awesomely simple, and the fact that the 3D version also works is why people love the slab method:

compute (tx0, tx1)

compute (ty0, ty1)

compute (tz0, tz1)

return overlap ? ((tx0, tx1), (ty0, ty1), (tz0, tz1))

There are some caveats that make this less pretty than it first appears. First, suppose the ray is

travelling in the negative $\mathbf{x}$ direction. The interval $(t_{x0}, t_{x1})$ as computed above

might be reversed, e.g. something like $(7, 3)$. Second, the divide in there could give us

infinities. And if the ray origin is on one of the slab boundaries, we can get a NaN. There are

many ways these issues are dealt with in various ray tracers’ AABB. (There are also vectorization

issues like SIMD which we will not discuss here. Ingo Wald’s papers are a great place to start if

you want to go the extra mile in vectorization for speed.) For our purposes, this is unlikely to be

a major bottleneck as long as we make it reasonably fast, so let’s go for simplest, which is often

fastest anyway! First let’s look at computing the intervals:

$$ t_{x0} = \frac{x_0 - A_x}{b_x} $$ $$ t_{x1} = \frac{x_1 - A_x}{b_x} $$

One troublesome thing is that perfectly valid rays will have $b_x = 0$, causing division by zero. Some of those rays are inside the slab, and some are not. Also, the zero will have a ± sign when using IEEE floating point. The good news for $b_x = 0$ is that $t_{x0}$ and $t_{x1}$ will both be +∞ or both be -∞ if not between $x_0$ and $x_1$. So, using min and max should get us the right answers:

$$ t_{x0} = \min( \frac{x_0 - A_x}{b_x}, \frac{x_1 - A_x}{b_x}) $$

$$ t_{x1} = \max( \frac{x_0 - A_x}{b_x}, \frac{x_1 - A_x}{b_x}) $$

The remaining troublesome case if we do that is if $b_x = 0$ and either $x_0 - A_x = 0$ or $x_1 -

A_x = 0$ so we get a NaN. In that case we can probably accept either hit or no hit answer, but

we’ll revisit that later.

Now, let’s look at that overlap function. Suppose we can assume the intervals are not reversed (so the first value is less than the second value in the interval) and we want to return true in that case. The boolean overlap that also computes the overlap interval $(f, F)$ of intervals $(d, D)$ and $(e, E)$ would be:

If there are any NaNs running around there, the compare will return false so we need to be sure

our bounding boxes have a little padding if we care about grazing cases (and we probably should

because in a ray tracer all cases come up eventually). Here's the implementation:

class interval {

public:

...

double size() const {

return max - min;

}

interval expand(double delta) const {

auto padding = delta/2;

return interval(min - padding, max + padding);

}

...

};

#ifndef AABB_H

#define AABB_H

#include "rtweekend.h"

class aabb {

public:

interval x, y, z;

aabb() {} // The default AABB is empty, since intervals are empty by default.

aabb(const interval& ix, const interval& iy, const interval& iz)

: x(ix), y(iy), z(iz) { }

aabb(const point3& a, const point3& b) {

// Treat the two points a and b as extrema for the bounding box, so we don't require a

// particular minimum/maximum coordinate order.

x = interval(fmin(a[0],b[0]), fmax(a[0],b[0]));

y = interval(fmin(a[1],b[1]), fmax(a[1],b[1]));

z = interval(fmin(a[2],b[2]), fmax(a[2],b[2]));

}

const interval& axis(int n) const {

if (n == 1) return y;

if (n == 2) return z;

return x;

}

bool hit(const ray& r, interval ray_t) const {

for (int a = 0; a < 3; a++) {

auto t0 = fmin((axis(a).min - r.origin()[a]) / r.direction()[a],

(axis(a).max - r.origin()[a]) / r.direction()[a]);

auto t1 = fmax((axis(a).min - r.origin()[a]) / r.direction()[a],

(axis(a).max - r.origin()[a]) / r.direction()[a]);

ray_t.min = fmax(t0, ray_t.min);

ray_t.max = fmin(t1, ray_t.max);

if (ray_t.max <= ray_t.min)

return false;

}

return true;

}

};

#endif

An Optimized AABB Hit Method

In reviewing this intersection method, Andrew Kensler at Pixar tried some experiments and proposed the following version of the code. It works extremely well on many compilers, and I have adopted it as my go-to method:

class aabb {

public:

...

bool hit(const ray& r, interval ray_t) const {

for (int a = 0; a < 3; a++) {

auto invD = 1 / r.direction()[a];

auto orig = r.origin()[a];

auto t0 = (axis(a).min - orig) * invD;

auto t1 = (axis(a).max - orig) * invD;

if (invD < 0)

std::swap(t0, t1);

if (t0 > ray_t.min) ray_t.min = t0;

if (t1 < ray_t.max) ray_t.max = t1;

if (ray_t.max <= ray_t.min)

return false;

}

return true;

}

...

};

Constructing Bounding Boxes for Hittables

We now need to add a function to compute the bounding boxes of all the hittables. Then we will make a hierarchy of boxes over all the primitives, and the individual primitives--like spheres--will live at the leaves.

Recall that interval values constructed without arguments will be empty by default. Since an

aabb object has an interval for each of its three dimensions, each of these will then be empty by

default, and therefore aabb objects will be empty by default. Thus, some objects may have empty

bounding volumes. For example, consider a hittable_list object with no children. Happily, the way

we've designed our interval class, the math all works out.

Finally, recall that some objects may be animated. Such objects should return their bounds over the entire range of motion, from time=0 to time=1.

#include "aabb.h"

...

class hittable {

public:

...

virtual bool hit(const ray& r, interval ray_t, hit_record& rec) const = 0;

virtual aabb bounding_box() const = 0;

...

};

For a stationary sphere, the bounding_box function is easy:

class sphere : public hittable {

public:

// Stationary Sphere

sphere(point3 _center, double _radius, shared_ptr<material> _material)

: center1(_center), radius(_radius), mat(_material), is_moving(false)

{

auto rvec = vec3(radius, radius, radius);

bbox = aabb(center1 - rvec, center1 + rvec);

}

...

aabb bounding_box() const override { return bbox; }

private:

point3 center1;

double radius;

shared_ptr<material> mat;

bool is_moving;

vec3 center_vec;

aabb bbox;

...

};

For a moving sphere, we want the bounds of its entire range of motion. To do this, we can take the box of the sphere at time=0, and the box of the sphere at time=1, and compute the box around those two boxes.

class sphere : public hittable {

public:

...

// Moving Sphere

sphere(point3 _center1, point3 _center2, double _radius, shared_ptr<material> _material)

: center1(_center1), radius(_radius), mat(_material), is_moving(true)

{

auto rvec = vec3(radius, radius, radius);

aabb box1(_center1 - rvec, _center1 + rvec);

aabb box2(_center2 - rvec, _center2 + rvec);

bbox = aabb(box1, box2);

center_vec = _center2 - _center1;

}

...

};

Now we need a new aabb constructor that takes two boxes as input.

First, we'll add a new interval constructor that takes two intervals as input:

class interval {

public:

...

interval(const interval& a, const interval& b)

: min(fmin(a.min, b.min)), max(fmax(a.max, b.max)) {}

Now we can use this to construct an axis-aligned bounding box from two input boxes.

class aabb {

public:

...

aabb(const aabb& box0, const aabb& box1) {

x = interval(box0.x, box1.x);

y = interval(box0.y, box1.y);

z = interval(box0.z, box1.z);

}

...

};

Creating Bounding Boxes of Lists of Objects

Now we'll update the hittable_list object, computing the bounds of its children. We'll update the

bounding box incrementally as each new child is added.

...

#include "aabb.h"

...

class hittable_list : public hittable {

public:

std::vector<shared_ptr<hittable>> objects;

...

void add(shared_ptr<hittable> object) {

objects.push_back(object);

bbox = aabb(bbox, object->bounding_box());

}

bool hit(const ray& r, double ray_tmin, double ray_tmax, hit_record& rec) const override {

...

}

aabb bounding_box() const override { return bbox; }

private:

aabb bbox;

};

The BVH Node Class

A BVH is also going to be a hittable -- just like lists of hittables. It’s really a container,

but it can respond to the query “does this ray hit you?”. One design question is whether we have two

classes, one for the tree, and one for the nodes in the tree; or do we have just one class and have

the root just be a node we point to. The hit function is pretty straightforward: check whether the

box for the node is hit, and if so, check the children and sort out any details.

I am a fan of the one class design when feasible. Here is such a class:

#ifndef BVH_H

#define BVH_H

#include "rtweekend.h"

#include "hittable.h"

#include "hittable_list.h"

class bvh_node : public hittable {

public:

bvh_node(const hittable_list& list) : bvh_node(list.objects, 0, list.objects.size()) {}

bvh_node(const std::vector<shared_ptr<hittable>>& src_objects, size_t start, size_t end) {

// To be implemented later.

}

bool hit(const ray& r, interval ray_t, hit_record& rec) const override {

if (!box.hit(r, ray_t))

return false;

bool hit_left = left->hit(r, ray_t, rec);

bool hit_right = right->hit(r, interval(ray_t.min, hit_left ? rec.t : ray_t.max), rec);

return hit_left || hit_right;

}

aabb bounding_box() const override { return bbox; }

private:

shared_ptr<hittable> left;

shared_ptr<hittable> right;

aabb bbox;

};

#endif

Splitting BVH Volumes

The most complicated part of any efficiency structure, including the BVH, is building it. We do this

in the constructor. A cool thing about BVHs is that as long as the list of objects in a bvh_node

gets divided into two sub-lists, the hit function will work. It will work best if the division is

done well, so that the two children have smaller bounding boxes than their parent’s bounding box,

but that is for speed not correctness. I’ll choose the middle ground, and at each node split the

list along one axis. I’ll go for simplicity:

- randomly choose an axis

- sort the primitives (

using std::sort) - put half in each subtree

When the list coming in is two elements, I put one in each subtree and end the recursion. The

traversal algorithm should be smooth and not have to check for null pointers, so if I just have one

element I duplicate it in each subtree. Checking explicitly for three elements and just following

one recursion would probably help a little, but I figure the whole method will get optimized later.

The following code uses three methods--box_x_compare, box_y_compare_, and box_z_compare--that

we haven't yet defined.

#include <algorithm>

class bvh_node : public hittable {

public:

...

bvh_node(const std::vector<shared_ptr<hittable>>& src_objects, size_t start, size_t end) {

auto objects = src_objects; // Create a modifiable array of the source scene objects

int axis = random_int(0,2);

auto comparator = (axis == 0) ? box_x_compare

: (axis == 1) ? box_y_compare

: box_z_compare;

size_t object_span = end - start;

if (object_span == 1) {

left = right = objects[start];

} else if (object_span == 2) {

if (comparator(objects[start], objects[start+1])) {

left = objects[start];

right = objects[start+1];

} else {

left = objects[start+1];

right = objects[start];

}

} else {

std::sort(objects.begin() + start, objects.begin() + end, comparator);

auto mid = start + object_span/2;

left = make_shared<bvh_node>(objects, start, mid);

right = make_shared<bvh_node>(objects, mid, end);

}

bbox = aabb(left->bounding_box(), right->bounding_box());

}

...

};

This uses a new function: random_int():

inline int random_int(int min, int max) {

// Returns a random integer in [min,max].

return static_cast<int>(random_double(min, max+1));

}

The check for whether there is a bounding box at all is in case you sent in something like an infinite plane that doesn’t have a bounding box. We don’t have any of those primitives, so it shouldn’t happen until you add such a thing.

The Box Comparison Functions

Now we need to implement the box comparison functions, used by std::sort(). To do this, create a

generic comparator returns true if the first argument is less than the second, given an additional

axis index argument. Then define axis-specific comparison functions that use the generic comparison

function.

class bvh_node : public hittable {

...

private:

...

static bool box_compare(

const shared_ptr<hittable> a, const shared_ptr<hittable> b, int axis_index

) {

return a->bounding_box().axis(axis_index).min < b->bounding_box().axis(axis_index).min;

}

static bool box_x_compare (const shared_ptr<hittable> a, const shared_ptr<hittable> b) {

return box_compare(a, b, 0);

}

static bool box_y_compare (const shared_ptr<hittable> a, const shared_ptr<hittable> b) {

return box_compare(a, b, 1);

}

static bool box_z_compare (const shared_ptr<hittable> a, const shared_ptr<hittable> b) {

return box_compare(a, b, 2);

}

};

At this point, we're ready to use our new BVH code. Let's use it on our random spheres scene.

...

int main() {

...

auto material2 = make_shared<lambertian>(color(0.4, 0.2, 0.1));

world.add(make_shared<sphere>(point3(-4, 1, 0), 1.0, material2));

auto material3 = make_shared<metal>(color(0.7, 0.6, 0.5), 0.0);

world.add(make_shared<sphere>(point3(4, 1, 0), 1.0, material3));

world = hittable_list(make_shared<bvh_node>(world));

camera cam;

...

}