Surface Normals and Multiple Objects

Shading with Surface Normals

First, let’s get ourselves a surface normal so we can shade. This is a vector that is perpendicular to the surface at the point of intersection.

We have a key design decision to make for normal vectors in our code: whether normal vectors will have an arbitrary length, or will be normalized to unit length.

It is tempting to skip the expensive square root operation involved in normalizing the vector, in

case it's not needed.

In practice, however, there are three important observations.

First, if a unit-length normal vector is ever required, then you might as well do it up front

once, instead of over and over again "just in case" for every location where unit-length is

required.

Second, we do require unit-length normal vectors in several places.

Third, if you require normal vectors to be unit length, then you can often efficiently generate that

vector with an understanding of the specific geometry class, in its constructor, or in the hit()

function.

For example, sphere normals can be made unit length simply by dividing by the sphere radius,

avoiding the square root entirely.

Given all of this, we will adopt the policy that all normal vectors will be of unit length.

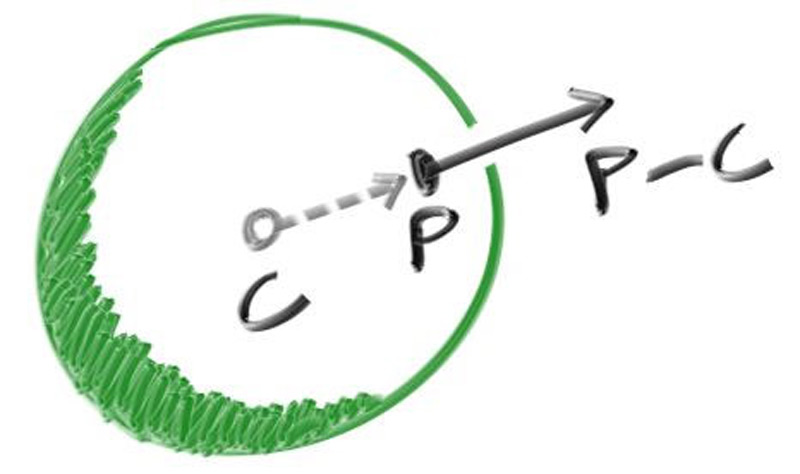

For a sphere, the outward normal is in the direction of the hit point minus the center:

On the earth, this means that the vector from the earth’s center to you points straight up. Let’s throw that into the code now, and shade it. We don’t have any lights or anything yet, so let’s just visualize the normals with a color map. A common trick used for visualizing normals (because it’s easy and somewhat intuitive to assume $\mathbf{n}$ is a unit length vector -- so each component is between -1 and 1) is to map each component to the interval from 0 to 1, and then map $(x, y, z)$ to $(\mathit{red}, \mathit{green}, \mathit{blue})$. For the normal, we need the hit point, not just whether we hit or not (which is all we're calculating at the moment). We only have one sphere in the scene, and it's directly in front of the camera, so we won't worry about negative values of $t$ yet. We'll just assume the closest hit point (smallest $t$) is the one that we want. These changes in the code let us compute and visualize $\mathbf{n}$:

double hit_sphere(const point3& center, double radius, const ray& r) {

vec3 oc = r.origin() - center;

auto a = dot(r.direction(), r.direction());

auto b = 2.0 * dot(oc, r.direction());

auto c = dot(oc, oc) - radius*radius;

auto discriminant = b*b - 4*a*c;

if (discriminant < 0) {

return -1.0;

} else {

return (-b - sqrt(discriminant) ) / (2.0*a);

}

}

color ray_color(const ray& r) {

auto t = hit_sphere(point3(0,0,-1), 0.5, r);

if (t > 0.0) {

vec3 N = unit_vector(r.at(t) - vec3(0,0,-1));

return 0.5*color(N.x()+1, N.y()+1, N.z()+1);

}

vec3 unit_direction = unit_vector(r.direction());

auto a = 0.5*(unit_direction.y() + 1.0);

return (1.0-a)*color(1.0, 1.0, 1.0) + a*color(0.5, 0.7, 1.0);

}

And that yields this picture:

Simplifying the Ray-Sphere Intersection Code

Let’s revisit the ray-sphere function:

double hit_sphere(const point3& center, double radius, const ray& r) {

vec3 oc = r.origin() - center;

auto a = dot(r.direction(), r.direction());

auto b = 2.0 * dot(oc, r.direction());

auto c = dot(oc, oc) - radius*radius;

auto discriminant = b*b - 4*a*c;

if (discriminant < 0) {

return -1.0;

} else {

return (-b - sqrt(discriminant) ) / (2.0*a);

}

}

First, recall that a vector dotted with itself is equal to the squared length of that vector.

Second, notice how the equation for b has a factor of two in it. Consider what happens to the

quadratic equation if $b = 2h$:

$$ \frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2 - 4ac}}{2a} $$

$$ = \frac{-2h \pm \sqrt{(2h)^2 - 4ac}}{2a} $$

$$ = \frac{-2h \pm 2\sqrt{h^2 - ac}}{2a} $$

$$ = \frac{-h \pm \sqrt{h^2 - ac}}{a} $$

Using these observations, we can now simplify the sphere-intersection code to this:

double hit_sphere(const point3& center, double radius, const ray& r) {

vec3 oc = r.origin() - center;

auto a = r.direction().length_squared();

auto half_b = dot(oc, r.direction());

auto c = oc.length_squared() - radius*radius;

auto discriminant = half_b*half_b - a*c;

if (discriminant < 0) {

return -1.0;

} else {

return (-half_b - sqrt(discriminant) ) / a;

}

}

An Abstraction for Hittable Objects

Now, how about more than one sphere? While it is tempting to have an array of spheres, a very clean solution is to make an “abstract class” for anything a ray might hit, and make both a sphere and a list of spheres just something that can be hit. What that class should be called is something of a quandary -- calling it an “object” would be good if not for “object oriented” programming. “Surface” is often used, with the weakness being maybe we will want volumes (fog, clouds, stuff like that). “hittable” emphasizes the member function that unites them. I don’t love any of these, but we'll go with “hittable”.

This hittable abstract class will have a hit function that takes in a ray. Most ray tracers

have found it convenient to add a valid interval for hits $t_{\mathit{min}}$ to $t_{\mathit{max}}$,

so the hit only “counts” if $t_{\mathit{min}} < t < t_{\mathit{max}}$. For the initial rays this is

positive $t$, but as we will see, it can simplify our code to have an interval

$t_{\mathit{min}}$ to $t_{\mathit{max}}$. One design question is whether to do things like compute

the normal if we hit something. We might end up hitting something closer as we do our search, and we

will only need the normal of the closest thing. I will go with the simple solution and compute a

bundle of stuff I will store in some structure. Here’s the abstract class:

#ifndef HITTABLE_H

#define HITTABLE_H

#include "ray.h"

class hit_record {

public:

point3 p;

vec3 normal;

double t;

};

class hittable {

public:

virtual ~hittable() = default;

virtual bool hit(const ray& r, double ray_tmin, double ray_tmax, hit_record& rec) const = 0;

};

#endif

And here’s the sphere:

#ifndef SPHERE_H

#define SPHERE_H

#include "hittable.h"

#include "vec3.h"

class sphere : public hittable {

public:

sphere(point3 _center, double _radius) : center(_center), radius(_radius) {}

bool hit(const ray& r, double ray_tmin, double ray_tmax, hit_record& rec) const override {

vec3 oc = r.origin() - center;

auto a = r.direction().length_squared();

auto half_b = dot(oc, r.direction());

auto c = oc.length_squared() - radius*radius;

auto discriminant = half_b*half_b - a*c;

if (discriminant < 0) return false;

auto sqrtd = sqrt(discriminant);

// Find the nearest root that lies in the acceptable range.

auto root = (-half_b - sqrtd) / a;

if (root <= ray_tmin || ray_tmax <= root) {

root = (-half_b + sqrtd) / a;

if (root <= ray_tmin || ray_tmax <= root)

return false;

}

rec.t = root;

rec.p = r.at(rec.t);

rec.normal = (rec.p - center) / radius;

return true;

}

private:

point3 center;

double radius;

};

#endif

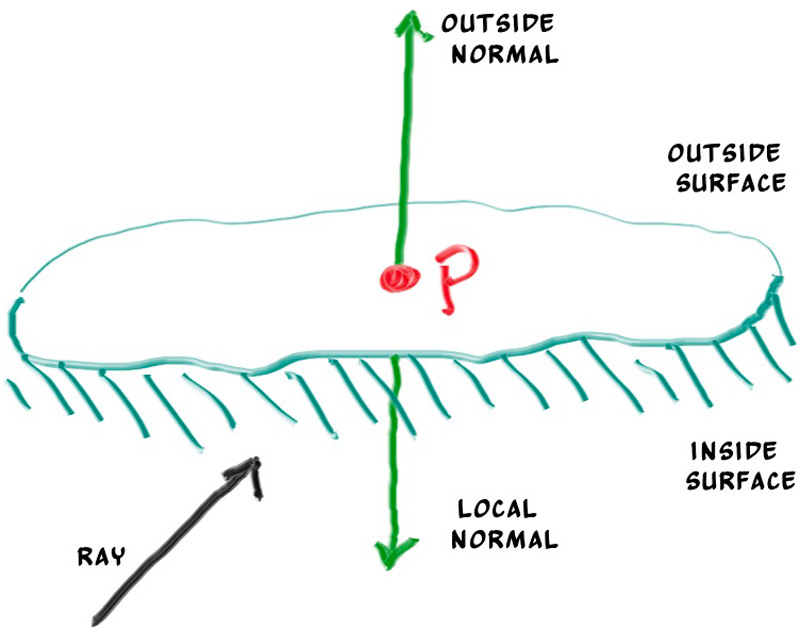

Front Faces Versus Back Faces

The second design decision for normals is whether they should always point out. At present, the normal found will always be in the direction of the center to the intersection point (the normal points out). If the ray intersects the sphere from the outside, the normal points against the ray. If the ray intersects the sphere from the inside, the normal (which always points out) points with the ray. Alternatively, we can have the normal always point against the ray. If the ray is outside the sphere, the normal will point outward, but if the ray is inside the sphere, the normal will point inward.

We need to choose one of these possibilities because we will eventually want to determine which side of the surface that the ray is coming from. This is important for objects that are rendered differently on each side, like the text on a two-sided sheet of paper, or for objects that have an inside and an outside, like glass balls.

If we decide to have the normals always point out, then we will need to determine which side the ray is on when we color it. We can figure this out by comparing the ray with the normal. If the ray and the normal face in the same direction, the ray is inside the object, if the ray and the normal face in the opposite direction, then the ray is outside the object. This can be determined by taking the dot product of the two vectors, where if their dot is positive, the ray is inside the sphere.

if (dot(ray_direction, outward_normal) > 0.0) {

// ray is inside the sphere

...

} else {

// ray is outside the sphere

...

}

If we decide to have the normals always point against the ray, we won't be able to use the dot product to determine which side of the surface the ray is on. Instead, we would need to store that information:

bool front_face;

if (dot(ray_direction, outward_normal) > 0.0) {

// ray is inside the sphere

normal = -outward_normal;

front_face = false;

} else {

// ray is outside the sphere

normal = outward_normal;

front_face = true;

}

We can set things up so that normals always point “outward” from the surface, or always point against the incident ray. This decision is determined by whether you want to determine the side of the surface at the time of geometry intersection or at the time of coloring. In this book we have more material types than we have geometry types, so we'll go for less work and put the determination at geometry time. This is simply a matter of preference, and you'll see both implementations in the literature.

We add the front_face bool to the hit_record class.

We'll also add a function to solve this calculation for us: set_face_normal().

For convenience we will assume that the vector passed to the new set_face_normal() function is of

unit length.

We could always normalize the parameter explicitly, but it's more efficient if the geometry code

does this, as it's usually easier when you know more about the specific geometry.

class hit_record {

public:

point3 p;

vec3 normal;

double t;

bool front_face;

void set_face_normal(const ray& r, const vec3& outward_normal) {

// Sets the hit record normal vector.

// NOTE: the parameter `outward_normal` is assumed to have unit length.

front_face = dot(r.direction(), outward_normal) < 0;

normal = front_face ? outward_normal : -outward_normal;

}

};

And then we add the surface side determination to the class:

class sphere : public hittable {

public:

...

bool hit(const ray& r, double ray_tmin, double ray_tmax, hit_record& rec) const {

...

rec.t = root;

rec.p = r.at(rec.t);

vec3 outward_normal = (rec.p - center) / radius;

rec.set_face_normal(r, outward_normal);

return true;

}

...

};

A List of Hittable Objects

We have a generic object called a hittable that the ray can intersect with. We now add a class

that stores a list of hittables:

#ifndef HITTABLE_LIST_H

#define HITTABLE_LIST_H

#include "hittable.h"

#include <memory>

#include <vector>

using std::shared_ptr;

using std::make_shared;

class hittable_list : public hittable {

public:

std::vector<shared_ptr<hittable>> objects;

hittable_list() {}

hittable_list(shared_ptr<hittable> object) { add(object); }

void clear() { objects.clear(); }

void add(shared_ptr<hittable> object) {

objects.push_back(object);

}

bool hit(const ray& r, double ray_tmin, double ray_tmax, hit_record& rec) const override {

hit_record temp_rec;

bool hit_anything = false;

auto closest_so_far = ray_tmax;

for (const auto& object : objects) {

if (object->hit(r, ray_tmin, closest_so_far, temp_rec)) {

hit_anything = true;

closest_so_far = temp_rec.t;

rec = temp_rec;

}

}

return hit_anything;

}

};

#endif

Some New C++ Features

The hittable_list class code uses two C++ features that may trip you up if you're not normally a

C++ programmer: vector and shared_ptr.

shared_ptr<type> is a pointer to some allocated type, with reference-counting semantics.

Every time you assign its value to another shared pointer (usually with a simple assignment), the

reference count is incremented. As shared pointers go out of scope (like at the end of a block or

function), the reference count is decremented. Once the count goes to zero, the object is safely

deleted.

Typically, a shared pointer is first initialized with a newly-allocated object, something like this:

shared_ptr<double> double_ptr = make_shared<double>(0.37);

shared_ptr<vec3> vec3_ptr = make_shared<vec3>(1.414214, 2.718281, 1.618034);

shared_ptr<sphere> sphere_ptr = make_shared<sphere>(point3(0,0,0), 1.0);

make_shared<thing>(thing_constructor_params ...) allocates a new instance of type thing, using

the constructor parameters. It returns a shared_ptr<thing>.

Since the type can be automatically deduced by the return type of make_shared<type>(...), the

above lines can be more simply expressed using C++'s auto type specifier:

auto double_ptr = make_shared<double>(0.37);

auto vec3_ptr = make_shared<vec3>(1.414214, 2.718281, 1.618034);

auto sphere_ptr = make_shared<sphere>(point3(0,0,0), 1.0);

We'll use shared pointers in our code, because it allows multiple geometries to share a common instance (for example, a bunch of spheres that all use the same color material), and because it makes memory management automatic and easier to reason about.

std::shared_ptr is included with the <memory> header.

The second C++ feature you may be unfamiliar with is std::vector. This is a generic array-like

collection of an arbitrary type. Above, we use a collection of pointers to hittable. std::vector

automatically grows as more values are added: objects.push_back(object) adds a value to the end of

the std::vector member variable objects.

std::vector is included with the <vector> header.

Finally, the using statements in listing [hittable-list-initial] tell the compiler that we'll be

getting shared_ptr and make_shared from the std library, so we don't need to prefix these with

std:: every time we reference them.

Common Constants and Utility Functions

We need some math constants that we conveniently define in their own header file. For now we only

need infinity, but we will also throw our own definition of pi in there, which we will need later.

There is no standard portable definition of pi, so we just define our own constant for it. We'll

throw common useful constants and future utility functions in rtweekend.h, our general main header

file.

#ifndef RTWEEKEND_H

#define RTWEEKEND_H

#include <cmath>

#include <limits>

#include <memory>

// Usings

using std::shared_ptr;

using std::make_shared;

using std::sqrt;

// Constants

const double infinity = std::numeric_limits<double>::infinity();

const double pi = 3.1415926535897932385;

// Utility Functions

inline double degrees_to_radians(double degrees) {

return degrees * pi / 180.0;

}

// Common Headers

#include "ray.h"

#include "vec3.h"

#endif

And the new main:

#include "rtweekend.h"

#include "color.h"

#include "hittable.h"

#include "hittable_list.h"

#include "sphere.h"

#include <iostream>

//double hit_sphere(const point3& center, double radius, const ray& r) {

// ...

//}

color ray_color(const ray& r, const hittable& world) {

hit_record rec;

if (world.hit(r, 0, infinity, rec)) {

return 0.5 * (rec.normal + color(1,1,1));

}

vec3 unit_direction = unit_vector(r.direction());

auto a = 0.5*(unit_direction.y() + 1.0);

return (1.0-a)*color(1.0, 1.0, 1.0) + a*color(0.5, 0.7, 1.0);

}

int main() {

// Image

auto aspect_ratio = 16.0 / 9.0;

int image_width = 400;

// Calculate the image height, and ensure that it's at least 1.

int image_height = static_cast<int>(image_width / aspect_ratio);

image_height = (image_height < 1) ? 1 : image_height;

// World

hittable_list world;

world.add(make_shared<sphere>(point3(0,0,-1), 0.5));

world.add(make_shared<sphere>(point3(0,-100.5,-1), 100));

// Camera

auto focal_length = 1.0;

auto viewport_height = 2.0;

auto viewport_width = viewport_height * (static_cast<double>(image_width)/image_height);

auto camera_center = point3(0, 0, 0);

// Calculate the vectors across the horizontal and down the vertical viewport edges.

auto viewport_u = vec3(viewport_width, 0, 0);

auto viewport_v = vec3(0, -viewport_height, 0);

// Calculate the horizontal and vertical delta vectors from pixel to pixel.

auto pixel_delta_u = viewport_u / image_width;

auto pixel_delta_v = viewport_v / image_height;

// Calculate the location of the upper left pixel.

auto viewport_upper_left = camera_center

- vec3(0, 0, focal_length) - viewport_u/2 - viewport_v/2;

auto pixel00_loc = viewport_upper_left + 0.5 * (pixel_delta_u + pixel_delta_v);

// Render

std::cout << "P3\n" << image_width << ' ' << image_height << "\n255\n";

for (int j = 0; j < image_height; ++j) {

std::clog << "\rScanlines remaining: " << (image_height - j) << ' ' << std::flush;

for (int i = 0; i < image_width; ++i) {

auto pixel_center = pixel00_loc + (i * pixel_delta_u) + (j * pixel_delta_v);

auto ray_direction = pixel_center - camera_center;

ray r(camera_center, ray_direction);

color pixel_color = ray_color(r, world);

write_color(std::cout, pixel_color);

}

}

std::clog << "\rDone. \n";

}

This yields a picture that is really just a visualization of where the spheres are located along with their surface normal. This is often a great way to view any flaws or specific characteristics of a geometric model.

An Interval Class

Before we continue, we'll implement an interval class to manage real-valued intervals with a minimum and a maximum. We'll end up using this class quite often as we proceed.

#ifndef INTERVAL_H

#define INTERVAL_H

class interval {

public:

double min, max;

interval() : min(+infinity), max(-infinity) {} // Default interval is empty

interval(double _min, double _max) : min(_min), max(_max) {}

bool contains(double x) const {

return min <= x && x <= max;

}

bool surrounds(double x) const {

return min < x && x < max;

}

static const interval empty, universe;

};

const static interval empty (+infinity, -infinity);

const static interval universe(-infinity, +infinity);

#endif

// Common Headers

#include "interval.h"

#include "ray.h"

#include "vec3.h"

class hittable {

public:

...

virtual bool hit(const ray& r, interval ray_t, hit_record& rec) const = 0;

};

class hittable_list : public hittable {

public:

...

bool hit(const ray& r, interval ray_t, hit_record& rec) const override {

hit_record temp_rec;

bool hit_anything = false;

auto closest_so_far = ray_t.max;

for (const auto& object : objects) {

if (object->hit(r, interval(ray_t.min, closest_so_far), temp_rec)) {

hit_anything = true;

closest_so_far = temp_rec.t;

rec = temp_rec;

}

}

return hit_anything;

}

...

};

class sphere : public hittable {

public:

...

bool hit(const ray& r, interval ray_t, hit_record& rec) const override {

...

// Find the nearest root that lies in the acceptable range.

auto root = (-half_b - sqrtd) / a;

if (!ray_t.surrounds(root)) {

root = (-half_b + sqrtd) / a;

if (!ray_t.surrounds(root))

return false;

}

...

}

...

};

...

color ray_color(const ray& r, const hittable& world) {

hit_record rec;

if (world.hit(r, interval(0, infinity), rec)) {

return 0.5 * (rec.normal + color(1,1,1));

}

vec3 unit_direction = unit_vector(r.direction());

auto a = 0.5*(unit_direction.y() + 1.0);

return (1.0-a)*color(1.0, 1.0, 1.0) + a*color(0.5, 0.7, 1.0);

}

...