Output an image

The PPM Image Format

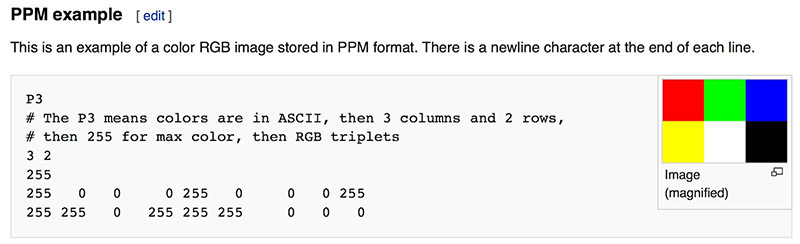

Whenever you start a renderer, you need a way to see an image. The most straightforward way is to write it to a file. The catch is, there are so many formats. Many of those are complex. I always start with a plain text ppm file. Here’s a nice description from Wikipedia:

Let’s make some code to output such a thing:

#include <iostream>

int main() {

// Image

int image_width = 256;

int image_height = 256;

// Render

std::cout << "P3\n" << image_width << ' ' << image_height << "\n255\n";

for (int j = 0; j < image_height; ++j) {

for (int i = 0; i < image_width; ++i) {

auto r = double(i) / (image_width-1);

auto g = double(j) / (image_height-1);

auto b = 0;

int ir = static_cast<int>(255.999 * r);

int ig = static_cast<int>(255.999 * g);

int ib = static_cast<int>(255.999 * b);

std::cout << ir << ' ' << ig << ' ' << ib << '\n';

}

}

}

fn main() {

let img_width = 256;

let img_height = 256;

println!("P3\n{} {}\n255\n", img_width, img_height);

for j in (0..img_height).rev() {

for i in 0..img_width {

let r = i as f32 / (img_width - 1) as f32;

let g = j as f32 / (img_height - 1) as f32;

let b = 0.25;

let ir = (255.99 * r) as i32;

let ig = (255.99 * g) as i32;

let ib = (255.99 * b) as i32;

println!("{} {} {}", ir, ig, ib);

}

}

}

There are some things to note in this code:

-

The pixels are written out in rows.

-

Every row of pixels is written out left to right.

-

These rows are written out from top to bottom.

-

By convention, each of the red/green/blue components are represented internally by real-valued variables that range from 0.0 to 1.0. These must be scaled to integer values between 0 and 255 before we print them out.

-

Red goes from fully off (black) to fully on (bright red) from left to right, and green goes from fully off at the top to black at the bottom. Adding red and green light together make yellow so we should expect the bottom right corner to be yellow.

Creating an Image File

Because the file is written to the standard output stream, you'll need to redirect it to an image

file. Typically this is done from the command-line by using the > redirection operator, like so:

(This example assumes that you are building with CMake, using the same approach as the

CMakeLists.txt file in the included source. Use whatever build environment (and language) you're

comfortable with.)

This is how things would look on Windows with CMake. On Mac or Linux, it might look like this:

Opening the output file (in ToyViewer on my Mac, but try it in your favorite image viewer and

Google “ppm viewer” if your viewer doesn’t support it) shows this result:

Hooray! This is the graphics “hello world”. If your image doesn’t look like that, open the output file in a text editor and see what it looks like. It should start something like this:

P3

256 256

255

0 0 0

1 0 0

2 0 0

3 0 0

4 0 0

5 0 0

6 0 0

7 0 0

8 0 0

9 0 0

10 0 0

11 0 0

12 0 0

...

If your PPM file doesn't look like this, then double-check your formatting code.

If it does look like this but fails to render, then you may have line-ending differences or

something similar that is confusing your image viewer.

To help debug this, you can find a file test.ppm in the images directory of the Github project.

This should help to ensure that your viewer can handle the PPM format and to use as a comparison

against your generated PPM file.

Some readers have reported problems viewing their generated files on Windows. In this case, the problem is often that the PPM is written out as UTF-16, often from PowerShell. If you run into this problem, see Discussion 1114 for help with this issue.

If everything displays correctly, then you're pretty much done with system and IDE issues -- everything in the remainder of this series uses this same simple mechanism for generated rendered images.

If you want to produce other image formats, I am a fan of stb_image.h, a header-only image library

available on GitHub at https://github.com/nothings/stb.

Adding a Progress Indicator

Before we continue, let's add a progress indicator to our output. This is a handy way to track the progress of a long render, and also to possibly identify a run that's stalled out due to an infinite loop or other problem.

Our program outputs the image to the standard output stream (std::cout), so leave that alone and

instead write to the logging output stream (std::clog):

for (int j = 0; j < image_height; ++j) {

std::clog << "\rScanlines remaining: " << (image_height - j) << ' ' << std::flush;

for (int i = 0; i < image_width; ++i) {

auto r = double(i) / (image_width-1);

auto g = double(j) / (image_height-1);

auto b = 0;

int ir = static_cast<int>(255.999 * r);

int ig = static_cast<int>(255.999 * g);

int ib = static_cast<int>(255.999 * b);

std::cout << ir << ' ' << ig << ' ' << ib << '\n';

}

}

std::clog << "\rDone. \n";

for j in (0..img_height).rev() {

// 这个 \r 可以清空当前一行

eprint!("\rScanlines remaining: {} ", j);

for i in 0..img_width {

let r = i as f32 / (img_width - 1) as f32;

let g = j as f32 / (img_height - 1) as f32;

let b = 0.25;

let ir = (255.99 * r) as i32;

let ig = (255.99 * g) as i32;

let ib = (255.99 * b) as i32;

println!("{} {} {}", ir, ig, ib);

}

}

// clear

eprint!("\r");

Now when running, you'll see a running count of the number of scanlines remaining. Hopefully this runs so fast that you don't even see it! Don't worry -- you'll have lots of time in the future to watch a slowly updating progress line as we expand our ray tracer.