Metal

An Abstract Class for Materials

If we want different objects to have different materials, we have a design decision. We could have a universal material type with lots of parameters so any individual material type could just ignore the parameters that don't affect it. This is not a bad approach. Or we could have an abstract material class that encapsulates unique behavior. I am a fan of the latter approach. For our program the material needs to do two things:

- Produce a scattered ray (or say it absorbed the incident ray).

- If scattered, say how much the ray should be attenuated.

This suggests the abstract class:

#ifndef MATERIAL_H

#define MATERIAL_H

#include "rtweekend.h"

class hit_record;

class material {

public:

virtual ~material() = default;

virtual bool scatter(

const ray& r_in, const hit_record& rec, color& attenuation, ray& scattered) const = 0;

};

#endif

A Data Structure to Describe Ray-Object Intersections

The hit_record is to avoid a bunch of arguments so we can stuff whatever info we want in there.

You can use arguments instead of an encapsulated type, it’s just a matter of taste. Hittables and

materials need to be able to reference the other's type in code so there is some circularity of the

references. In C++ we add the line class material; to tell the compiler that material is a class

that will be defined later. Since we're just specifying a pointer to the class, the compiler

doesn't need to know the details of the class, solving the circular reference issue.

#include "rtweekend.h"

class material;

class hit_record {

public:

point3 p;

vec3 normal;

shared_ptr<material> mat;

double t;

bool front_face;

void set_face_normal(const ray& r, const vec3& outward_normal) {

front_face = dot(r.direction(), outward_normal) < 0;

normal = front_face ? outward_normal : -outward_normal;

}

};

hit_record is just a way to stuff a bunch of arguments into a class so we can send them as a

group. When a ray hits a surface (a particular sphere for example), the material pointer in the

hit_record will be set to point at the material pointer the sphere was given when it was set up in

main() when we start. When the ray_color() routine gets the hit_record it can call member

functions of the material pointer to find out what ray, if any, is scattered.

To achieve this, hit_record needs to be told the material that is assigned to the sphere.

class sphere : public hittable {

public:

sphere(point3 _center, double _radius, shared_ptr<material> _material)

: center(_center), radius(_radius), mat(_material) {}

bool hit(const ray& r, interval ray_t, hit_record& rec) const override {

...

rec.t = root;

rec.p = r.at(rec.t);

vec3 outward_normal = (rec.p - center) / radius;

rec.set_face_normal(r, outward_normal);

rec.mat = mat;

return true;

}

private:

point3 center;

double radius;

shared_ptr<material> mat;

};

Modeling Light Scatter and Reflectance

For the Lambertian (diffuse) case we already have, it can either always scatter and attenuate by its reflectance $R$, or it can sometimes scatter (with probabilty $1-R$) with no attenuation (where a ray that isn't scattered is just absorbed into the material). It could also be a mixture of both those strategies. We will choose to always scatter, so Lambertian materials become this simple class:

class material {

...

};

class lambertian : public material {

public:

lambertian(const color& a) : albedo(a) {}

bool scatter(const ray& r_in, const hit_record& rec, color& attenuation, ray& scattered)

const override {

auto scatter_direction = rec.normal + random_unit_vector();

scattered = ray(rec.p, scatter_direction);

attenuation = albedo;

return true;

}

private:

color albedo;

};

Note the third option that we could scatter with some fixed probability $p$ and have attenuation be $\mathit{albedo}/p$. Your choice.

If you read the code above carefully, you'll notice a small chance of mischief. If the random unit vector we generate is exactly opposite the normal vector, the two will sum to zero, which will result in a zero scatter direction vector. This leads to bad scenarios later on (infinities and NaNs), so we need to intercept the condition before we pass it on.

In service of this, we'll create a new vector method -- vec3::near_zero() -- that returns true if

the vector is very close to zero in all dimensions.

class vec3 {

...

double length_squared() const {

return e[0]*e[0] + e[1]*e[1] + e[2]*e[2];

}

bool near_zero() const {

// Return true if the vector is close to zero in all dimensions.

auto s = 1e-8;

return (fabs(e[0]) < s) && (fabs(e[1]) < s) && (fabs(e[2]) < s);

}

...

};

class lambertian : public material {

public:

lambertian(const color& a) : albedo(a) {}

bool scatter(const ray& r_in, const hit_record& rec, color& attenuation, ray& scattered)

const override {

auto scatter_direction = rec.normal + random_unit_vector();

// Catch degenerate scatter direction

if (scatter_direction.near_zero())

scatter_direction = rec.normal;

scattered = ray(rec.p, scatter_direction);

attenuation = albedo;

return true;

}

private:

color albedo;

};

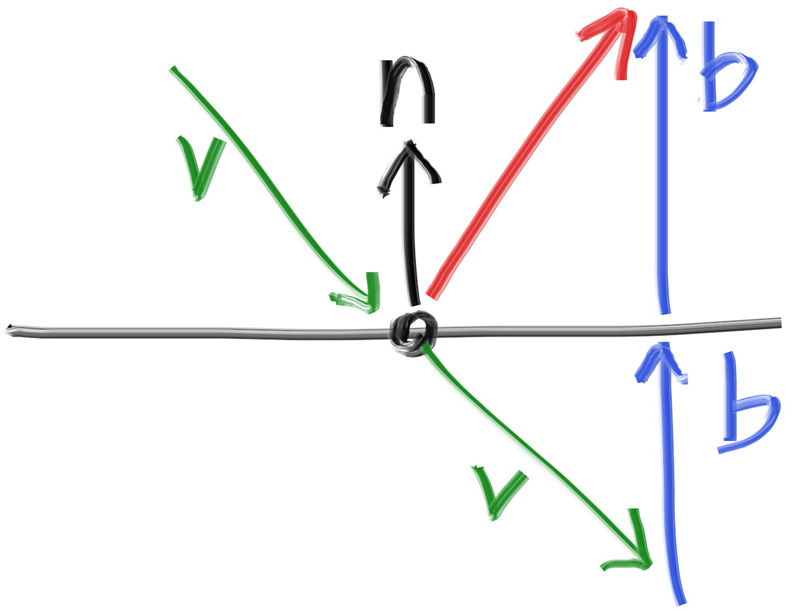

Mirrored Light Reflection

For polished metals the ray won’t be randomly scattered. The key question is: How does a ray get reflected from a metal mirror? Vector math is our friend here:

The reflected ray direction in red is just $\mathbf{v} + 2\mathbf{b}$. In our design, $\mathbf{n}$ is a unit vector, but $\mathbf{v}$ may not be. The length of $\mathbf{b}$ should be $\mathbf{v} \cdot \mathbf{n}$. Because $\mathbf{v}$ points in, we will need a minus sign, yielding:

...

inline vec3 random_on_hemisphere(const vec3& normal) {

...

}

vec3 reflect(const vec3& v, const vec3& n) {

return v - 2*dot(v,n)*n;

}

...

The metal material just reflects rays using that formula:

...

class lambertian : public material {

...

};

class metal : public material {

public:

metal(const color& a) : albedo(a) {}

bool scatter(const ray& r_in, const hit_record& rec, color& attenuation, ray& scattered)

const override {

vec3 reflected = reflect(unit_vector(r_in.direction()), rec.normal);

scattered = ray(rec.p, reflected);

attenuation = albedo;

return true;

}

private:

color albedo;

};

We need to modify the ray_color() function for all of our changes:

...

#include "rtweekend.h"

#include "color.h"

#include "hittable.h"

#include "material.h"

...

class camera {

...

private:

...

color ray_color(const ray& r, int depth, const hittable& world) const {

hit_record rec;

// If we've exceeded the ray bounce limit, no more light is gathered.

if (depth <= 0)

return color(0,0,0);

if (world.hit(r, interval(0.001, infinity), rec)) {

ray scattered;

color attenuation;

if (rec.mat->scatter(r, rec, attenuation, scattered))

return attenuation * ray_color(scattered, depth-1, world);

return color(0,0,0);

}

vec3 unit_direction = unit_vector(r.direction());

auto a = 0.5*(unit_direction.y() + 1.0);

return (1.0-a)*color(1.0, 1.0, 1.0) + a*color(0.5, 0.7, 1.0);

}

};

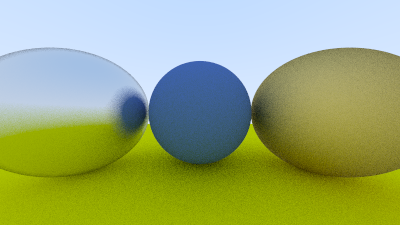

A Scene with Metal Spheres

Now let’s add some metal spheres to our scene:

#include "rtweekend.h"

#include "camera.h"

#include "color.h"

#include "hittable_list.h"

#include "material.h"

#include "sphere.h"

int main() {

hittable_list world;

auto material_ground = make_shared<lambertian>(color(0.8, 0.8, 0.0));

auto material_center = make_shared<lambertian>(color(0.7, 0.3, 0.3));

auto material_left = make_shared<metal>(color(0.8, 0.8, 0.8));

auto material_right = make_shared<metal>(color(0.8, 0.6, 0.2));

world.add(make_shared<sphere>(point3( 0.0, -100.5, -1.0), 100.0, material_ground));

world.add(make_shared<sphere>(point3( 0.0, 0.0, -1.0), 0.5, material_center));

world.add(make_shared<sphere>(point3(-1.0, 0.0, -1.0), 0.5, material_left));

world.add(make_shared<sphere>(point3( 1.0, 0.0, -1.0), 0.5, material_right));

camera cam;

cam.aspect_ratio = 16.0 / 9.0;

cam.image_width = 400;

cam.samples_per_pixel = 100;

cam.max_depth = 50;

cam.render(world);

}

Which gives:

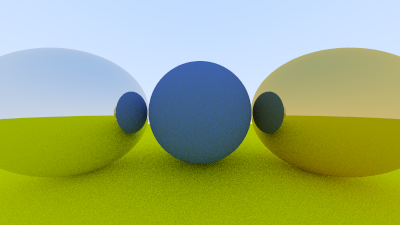

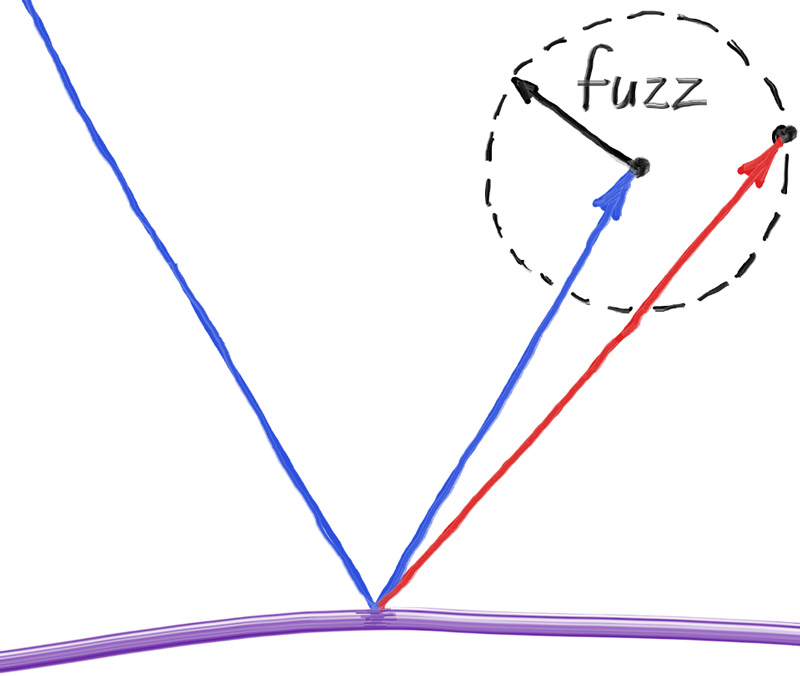

Fuzzy Reflection

We can also randomize the reflected direction by using a small sphere and choosing a new endpoint for the ray. We'll use a random point from the surface of a sphere centered on the original endpoint, scaled by the fuzz factor.

The bigger the sphere, the fuzzier the reflections will be. This suggests adding a fuzziness parameter that is just the radius of the sphere (so zero is no perturbation). The catch is that for big spheres or grazing rays, we may scatter below the surface. We can just have the surface absorb those.

class metal : public material {

public:

metal(const color& a, double f) : albedo(a), fuzz(f < 1 ? f : 1) {}

bool scatter(const ray& r_in, const hit_record& rec, color& attenuation, ray& scattered)

const override {

vec3 reflected = reflect(unit_vector(r_in.direction()), rec.normal);

scattered = ray(rec.p, reflected + fuzz*random_unit_vector());

attenuation = albedo;

return (dot(scattered.direction(), rec.normal) > 0);

}

private:

color albedo;

double fuzz;

};

We can try that out by adding fuzziness 0.3 and 1.0 to the metals:

int main() {

...

auto material_ground = make_shared<lambertian>(color(0.8, 0.8, 0.0));

auto material_center = make_shared<lambertian>(color(0.7, 0.3, 0.3));

auto material_left = make_shared<metal>(color(0.8, 0.8, 0.8), 0.3);

auto material_right = make_shared<metal>(color(0.8, 0.6, 0.2), 1.0);

...

}