Diffuse Materials

Now that we have objects and multiple rays per pixel, we can make some realistic looking materials. We’ll start with diffuse materials (also called matte). One question is whether we mix and match geometry and materials (so that we can assign a material to multiple spheres, or vice versa) or if geometry and materials are tightly bound (which could be useful for procedural objects where the geometry and material are linked). We’ll go with separate -- which is usual in most renderers -- but do be aware that there are alternative approaches.

A Simple Diffuse Material

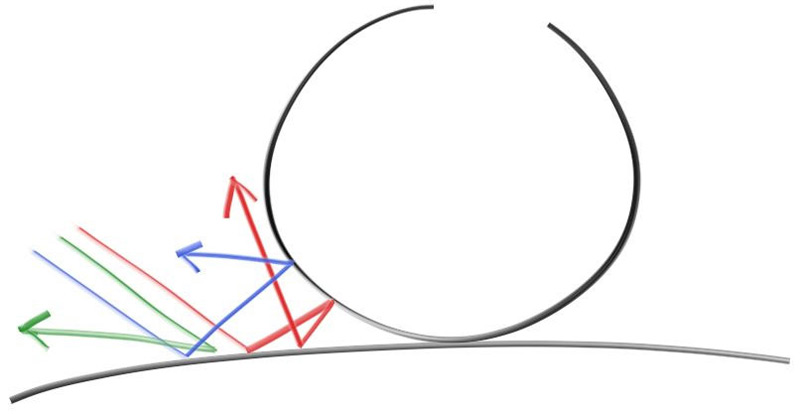

Diffuse objects that don’t emit their own light merely take on the color of their surroundings, but they do modulate that with their own intrinsic color. Light that reflects off a diffuse surface has its direction randomized, so, if we send three rays into a crack between two diffuse surfaces they will each have different random behavior:

They might also be absorbed rather than reflected. The darker the surface, the more likely the ray is absorbed (that’s why it's dark!). Really any algorithm that randomizes direction will produce surfaces that look matte. Let's start with the most intuitive: a surface that randomly bounces a ray equally in all directions. For this material, a ray that hits the surface has an equal probability of bouncing in any direction away from the surface.

This very intuitive material is the simplest kind of diffuse and -- indeed -- many of the first raytracing papers used this diffuse method (before adopting a more accurate method that we'll be implementing a little bit later). We don't currently have a way to randomly reflect a ray, so we'll need to add a few functions to our vector utility header. The first thing we need is the ability to generate arbitrary random vectors:

class vec3 {

public:

...

double length_squared() const {

return e[0]*e[0] + e[1]*e[1] + e[2]*e[2];

}

static vec3 random() {

return vec3(random_double(), random_double(), random_double());

}

static vec3 random(double min, double max) {

return vec3(random_double(min,max), random_double(min,max), random_double(min,max));

}

};

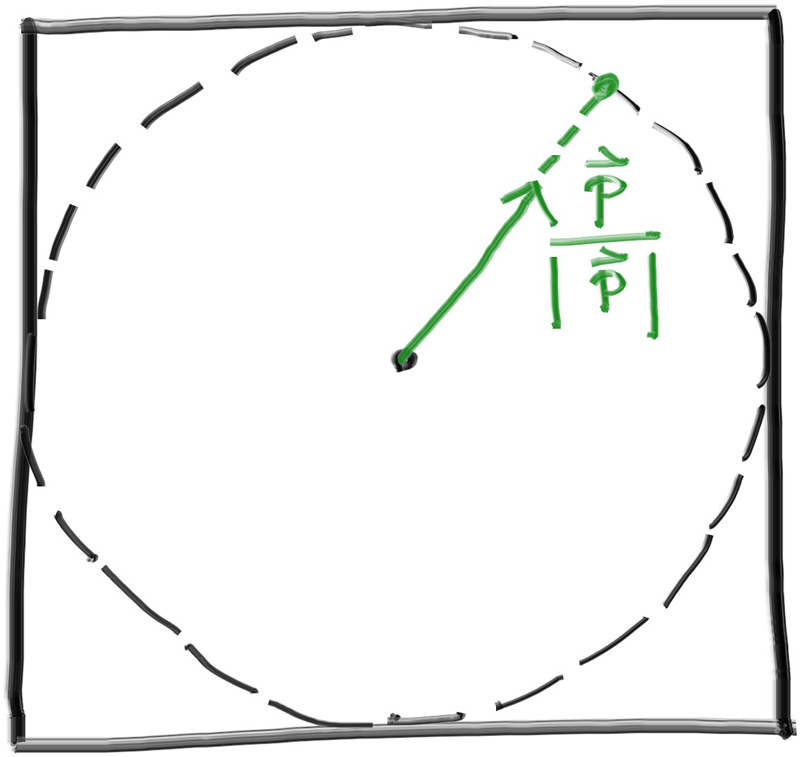

Then we need to figure out how to manipulate a random vector so that we only get results that are on the surface of a hemisphere. There are analytical methods of doing this, but they are actually surprisingly complicated to understand, and quite a bit complicated to implement. Instead, we'll use what is typically the easiest algorithm: A rejection method. A rejection method works by repeatedly generating random samples until we produce a sample that meets the desired criteria. In other words, keep rejecting samples until you find a good one.

There are many equally valid ways of generating a random vector on a hemisphere using the rejection method, but for our purposes we will go with the simplest, which is:

- Generate a random vector inside of the unit sphere

- Normalize this vector

- Invert the normalized vector if it falls onto the wrong hemisphere

First, we will use a rejection method to generate the random vector inside of the unit sphere. Pick a random point in the unit cube, where $x$, $y$, and $z$ all range from -1 to +1, and reject this point if it is outside the unit sphere.

...

inline vec3 unit_vector(vec3 v) {

return v / v.length();

}

inline vec3 random_in_unit_sphere() {

while (true) {

auto p = vec3::random(-1,1);

if (p.length_squared() < 1)

return p;

}

}

Once we have a random vector in the unit sphere we need to normalize it to get a vector on the unit sphere.

...

inline vec3 random_in_unit_sphere() {

while (true) {

auto p = vec3::random(-1,1);

if (p.length_squared() < 1)

return p;

}

}

inline vec3 random_unit_vector() {

return unit_vector(random_in_unit_sphere());

}

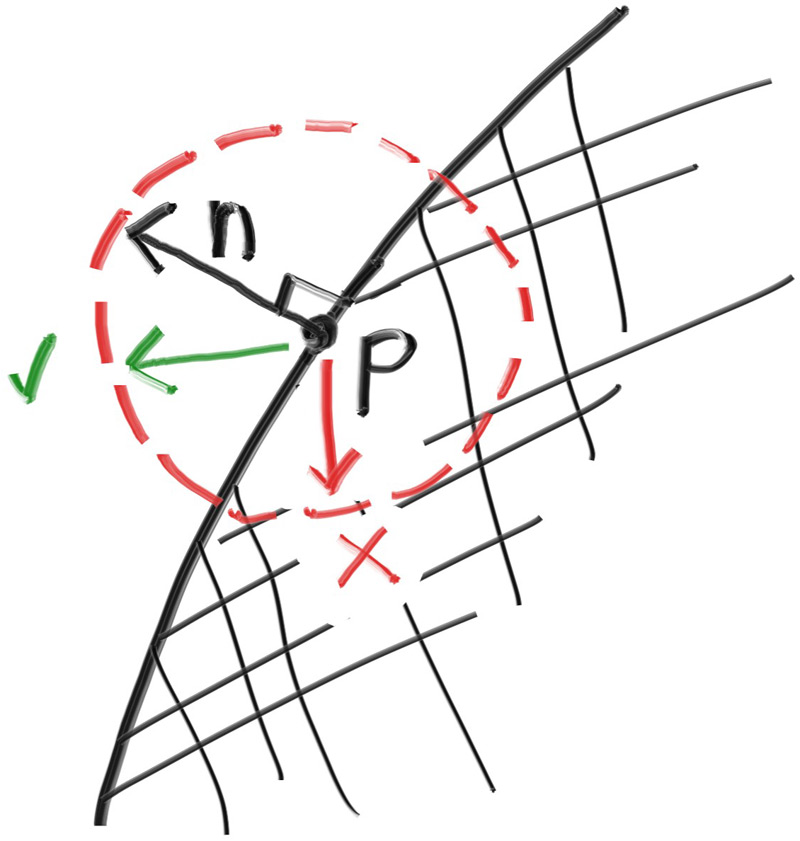

And now that we have a random vector on the surface of the unit sphere, we can determine if it is on the correct hemisphere by comparing against the surface normal:

We can take the dot product of the surface normal and our random vector to determine if it's in the correct hemisphere. If the dot product is positive, then the vector is in the correct hemisphere. If the dot product is negative, then we need to invert the vector.

...

inline vec3 random_unit_vector() {

return unit_vector(random_in_unit_sphere());

}

inline vec3 random_on_hemisphere(const vec3& normal) {

vec3 on_unit_sphere = random_unit_vector();

if (dot(on_unit_sphere, normal) > 0.0) // In the same hemisphere as the normal

return on_unit_sphere;

else

return -on_unit_sphere;

}

If a ray bounces off of a material and keeps 100% of its color, then we say that the material is

white. If a ray bounces off of a material and keeps 0% of its color, then we say that the

material is black. As a first demonstration of our new diffuse material we'll set the ray_color

function to return 50% of the color from a bounce. We should expect to get a nice gray color.

class camera {

...

private:

...

color ray_color(const ray& r, const hittable& world) const {

hit_record rec;

if (world.hit(r, interval(0, infinity), rec)) {

vec3 direction = random_on_hemisphere(rec.normal);

return 0.5 * ray_color(ray(rec.p, direction), world);

}

vec3 unit_direction = unit_vector(r.direction());

auto a = 0.5*(unit_direction.y() + 1.0);

return (1.0-a)*color(1.0, 1.0, 1.0) + a*color(0.5, 0.7, 1.0);

}

};

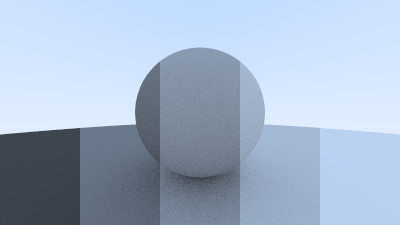

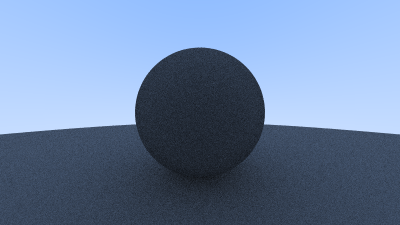

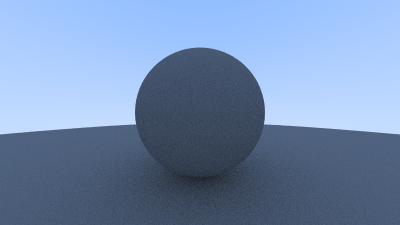

... Indeed we do get rather nice gray spheres:

Limiting the Number of Child Rays

There's one potential problem lurking here. Notice that the ray_color function is recursive. When

will it stop recursing? When it fails to hit anything. In some cases, however, that may be a long

time — long enough to blow the stack. To guard against that, let's limit the maximum recursion

depth, returning no light contribution at the maximum depth:

class camera {

public:

double aspect_ratio = 1.0; // Ratio of image width over height

int image_width = 100; // Rendered image width in pixel count

int samples_per_pixel = 10; // Count of random samples for each pixel

int max_depth = 10; // Maximum number of ray bounces into scene

void render(const hittable& world) {

initialize();

std::cout << "P3\n" << image_width << ' ' << image_height << "\n255\n";

for (int j = 0; j < image_height; ++j) {

std::clog << "\rScanlines remaining: " << (image_height - j) << ' ' << std::flush;

for (int i = 0; i < image_width; ++i) {

color pixel_color(0,0,0);

for (int sample = 0; sample < samples_per_pixel; ++sample) {

ray r = get_ray(i, j);

pixel_color += ray_color(r, max_depth, world);

}

write_color(std::cout, pixel_color, samples_per_pixel);

}

}

std::clog << "\rDone. \n";

}

...

private:

...

color ray_color(const ray& r, int depth, const hittable& world) const {

hit_record rec;

// If we've exceeded the ray bounce limit, no more light is gathered.

if (depth <= 0)

return color(0,0,0);

if (world.hit(r, interval(0, infinity), rec)) {

vec3 direction = random_on_hemisphere(rec.normal);

return 0.5 * ray_color(ray(rec.p, direction), depth-1, world);

}

vec3 unit_direction = unit_vector(r.direction());

auto a = 0.5*(unit_direction.y() + 1.0);

return (1.0-a)*color(1.0, 1.0, 1.0) + a*color(0.5, 0.7, 1.0);

}

};

Update the main() function to use this new depth limit:

int main() {

...

camera cam;

cam.aspect_ratio = 16.0 / 9.0;

cam.image_width = 400;

cam.samples_per_pixel = 100;

cam.max_depth = 50;

cam.render(world);

}

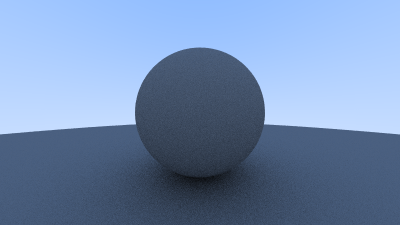

For this very simple scene we should get basically the same result:

Fixing Shadow Acne

There’s also a subtle bug that we need to address. A ray will attempt to accurately calculate the intersection point when it intersects with a surface. Unfortunately for us, this calculation is susceptible to floating point rounding errors which can cause the intersection point to be ever so slightly off. This means that the origin of the next ray, the ray that is randomly scattered off of the surface, is unlikely to be perfectly flush with the surface. It might be just above the surface. It might be just below the surface. If the ray's origin is just below the surface then it could intersect with that surface again. Which means that it will find the nearest surface at $t=0.00000001$ or whatever floating point approximation the hit function gives us. The simplest hack to address this is just to ignore hits that are very close to the calculated intersection point:

class camera {

...

private:

...

color ray_color(const ray& r, int depth, const hittable& world) const {

hit_record rec;

// If we've exceeded the ray bounce limit, no more light is gathered.

if (depth <= 0)

return color(0,0,0);

if (world.hit(r, interval(0.001, infinity), rec)) {

vec3 direction = random_on_hemisphere(rec.normal);

return 0.5 * ray_color(ray(rec.p, direction), depth-1, world);

}

vec3 unit_direction = unit_vector(r.direction());

auto a = 0.5*(unit_direction.y() + 1.0);

return (1.0-a)*color(1.0, 1.0, 1.0) + a*color(0.5, 0.7, 1.0);

}

};

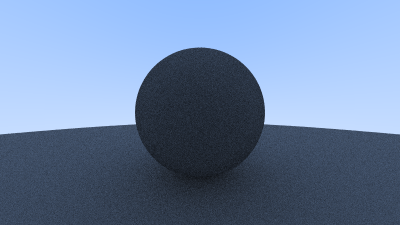

This gets rid of the shadow acne problem. Yes it is really called that. Here's the result:

True Lambertian Reflection

Scattering reflected rays evenly about the hemisphere produces a nice soft diffuse model, but we can definitely do better. A more accurate representation of real diffuse objects is the Lambertian distribution. This distribution scatters reflected rays in a manner that is proportional to $\cos (\phi)$, where $\phi$ is the angle between the reflected ray and the surface normal. This means that a reflected ray is most likely to scatter in a direction near the surface normal, and less likely to scatter in directions away from the normal. This non-uniform Lambertian distribution does a better job of modeling material reflection in the real world than our previous uniform scattering.

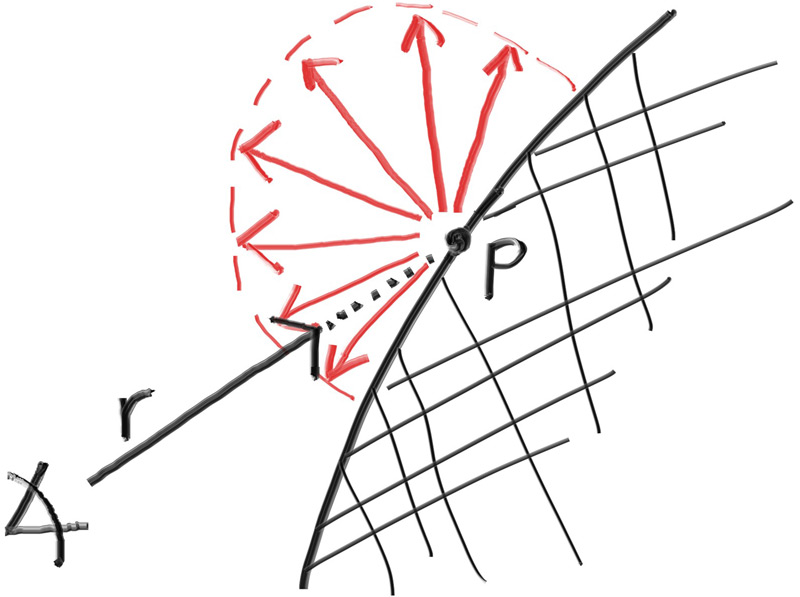

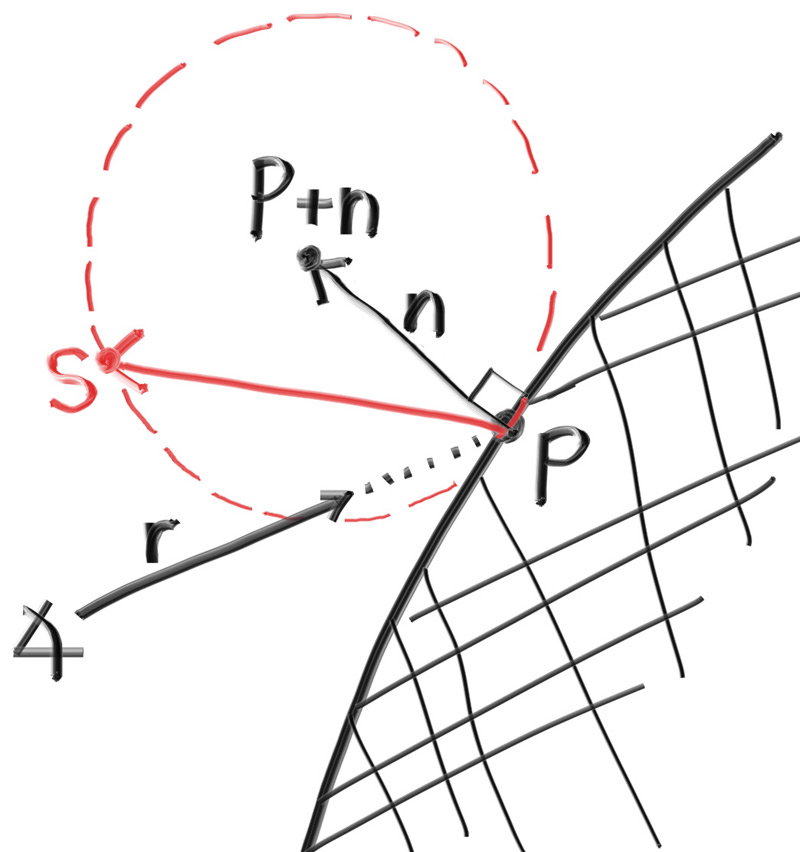

We can create this distribution by adding a random unit vector to the normal vector. At the point of intersection on a surface there is the hit point, $\mathbf{p}$, and there is the normal of the surface, $\mathbf{n}$. At the point of intersection, this surface has exactly two sides, so there can only be two unique unit spheres tangent to any intersection point (one unique sphere for each side of the surface). These two unit spheres will be displaced from the surface by the length of their radius, which is exactly one for a unit sphere.

One sphere will be displaced in the direction of the surface's normal ($\mathbf{n}$) and one sphere will be displaced in the opposite direction ($\mathbf{-n}$). This leaves us with two spheres of unit size that will only be just touching the surface at the intersection point. From this, one of the spheres will have its center at $(\mathbf{P} + \mathbf{n})$ and the other sphere will have its center at $(\mathbf{P} - \mathbf{n})$. The sphere with a center at $(\mathbf{P} - \mathbf{n})$ is considered inside the surface, whereas the sphere with center $(\mathbf{P} + \mathbf{n})$ is considered outside the surface.

We want to select the tangent unit sphere that is on the same side of the surface as the ray origin. Pick a random point $\mathbf{S}$ on this unit radius sphere and send a ray from the hit point $\mathbf{P}$ to the random point $\mathbf{S}$ (this is the vector $(\mathbf{S}-\mathbf{P})$):

The change is actually fairly minimal:

class camera {

...

color ray_color(const ray& r, int depth, const hittable& world) const {

hit_record rec;

// If we've exceeded the ray bounce limit, no more light is gathered.

if (depth <= 0)

return color(0,0,0);

if (world.hit(r, interval(0.001, infinity), rec)) {

vec3 direction = rec.normal + random_unit_vector();

return 0.5 * ray_color(ray(rec.p, direction), depth-1, world);

}

vec3 unit_direction = unit_vector(r.direction());

auto a = 0.5*(unit_direction.y() + 1.0);

return (1.0-a)*color(1.0, 1.0, 1.0) + a*color(0.5, 0.7, 1.0);

}

};

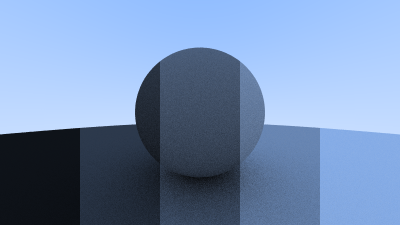

After rendering we get a similar image:

It's hard to tell the difference between these two diffuse methods, given that our scene of two spheres is so simple, but you should be able to notice two important visual differences:

- The shadows are more pronounced after the change

- Both spheres are tinted blue from the sky after the change

Both of these changes are due to the less uniform scattering of the light rays--more rays are scattering toward the normal. This means that for diffuse objects, they will appear darker because less light bounces toward the camera. For the shadows, more light bounces straight-up, so the area underneath the sphere is darker.

Not a lot of common, everyday objects are perfectly diffuse, so our visual intuition of how these objects behave under light can be poorly formed. As scenes become more complicated over the course of the book, you are encouraged to switch between the different diffuse renderers presented here. Most scenes of interest will contain a large amount of diffuse materials. You can gain valuable insight by understanding the effect of different diffuse methods on the lighting of a scene.

Using Gamma Correction for Accurate Color Intensity

Note the shadowing under the sphere. The picture is very dark, but our spheres only absorb half the

energy of each bounce, so they are 50% reflectors. The spheres should look pretty bright (in real

life, a light grey) but they appear to be rather dark. We can see this more clearly if we walk

through the full brightness gamut for our diffuse material. We start by setting the reflectance of

the ray_color function from 0.5 (50%) to 0.1 (10%):

class camera {

...

color ray_color(const ray& r, int depth, const hittable& world) const {

hit_record rec;

// If we've exceeded the ray bounce limit, no more light is gathered.

if (depth <= 0)

return color(0,0,0);

if (world.hit(r, interval(0.001, infinity), rec)) {

vec3 direction = rec.normal + random_unit_vector();

return 0.1 * ray_color(ray(rec.p, direction), depth-1, world);

}

vec3 unit_direction = unit_vector(r.direction());

auto a = 0.5*(unit_direction.y() + 1.0);

return (1.0-a)*color(1.0, 1.0, 1.0) + a*color(0.5, 0.7, 1.0);

}

};

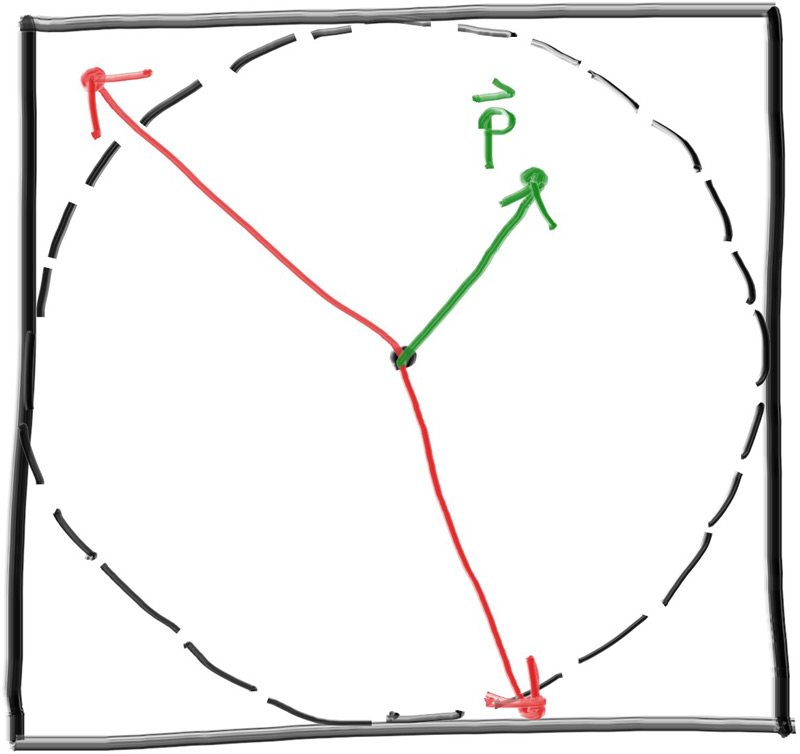

We render out at this new 10% reflectance. We then set reflectance to 30% and render again. We repeat for 50%, 70%, and finally 90%. You can overlay these images from left to right in the photo editor of your choice and you should get a very nice visual representation of the increasing brightness of your chosen gamut. This is the one that we've been working with so far:

If you look closely, or if you use a color picker, you should notice that the 50% reflectance render (the one in the middle) is far too dark to be half-way between white and black (middle-gray). Indeed, the 70% reflector is closer to middle-gray. The reason for this is that almost all computer programs assume that an image is “gamma corrected” before being written into an image file. This means that the 0 to 1 values have some transform applied before being stored as a byte. Images with data that are written without being transformed are said to be in linear space, whereas images that are transformed are said to be in gamma space. It is likely that the image viewer you are using is expecting an image in gamma space, but we are giving it an image in linear space. This is the reason why our image appears inaccurately dark.

There are many good reasons for why images should be stored in gamma space, but for our purposes we just need to be aware of it. We are going to transform our data into gamma space so that our image viewer can more accurately display our image. As a simple approximation, we can use “gamma 2” as our transform, which is the power that you use when going from gamma space to linear space. We need to go from linear space to gamma space, which means taking the inverse of "gamma 2", which means an exponent of $1/\mathit{gamma}$, which is just the square-root.

inline double linear_to_gamma(double linear_component)

{

return sqrt(linear_component);

}

void write_color(std::ostream &out, color pixel_color, int samples_per_pixel) {

auto r = pixel_color.x();

auto g = pixel_color.y();

auto b = pixel_color.z();

// Divide the color by the number of samples.

auto scale = 1.0 / samples_per_pixel;

r *= scale;

g *= scale;

b *= scale;

// Apply the linear to gamma transform.

r = linear_to_gamma(r);

g = linear_to_gamma(g);

b = linear_to_gamma(b);

// Write the translated [0,255] value of each color component.

static const interval intensity(0.000, 0.999);

out << static_cast<int>(256 * intensity.clamp(r)) << ' '

<< static_cast<int>(256 * intensity.clamp(g)) << ' '

<< static_cast<int>(256 * intensity.clamp(b)) << '\n';

}

Using this gamma correction, we now get a much more consistent ramp from darkness to lightness: