Dielectrics

Clear materials such as water, glass, and diamond are dielectrics. When a light ray hits them, it splits into a reflected ray and a refracted (transmitted) ray. We’ll handle that by randomly choosing between reflection and refraction, only generating one scattered ray per interaction.

Refraction

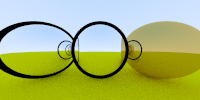

The hardest part to debug is the refracted ray. I usually first just have all the light refract if there is a refraction ray at all. For this project, I tried to put two glass balls in our scene, and I got this (I have not told you how to do this right or wrong yet, but soon!):

Is that right? Glass balls look odd in real life. But no, it isn’t right. The world should be flipped upside down and no weird black stuff. I just printed out the ray straight through the middle of the image and it was clearly wrong. That often does the job.

Snell's Law

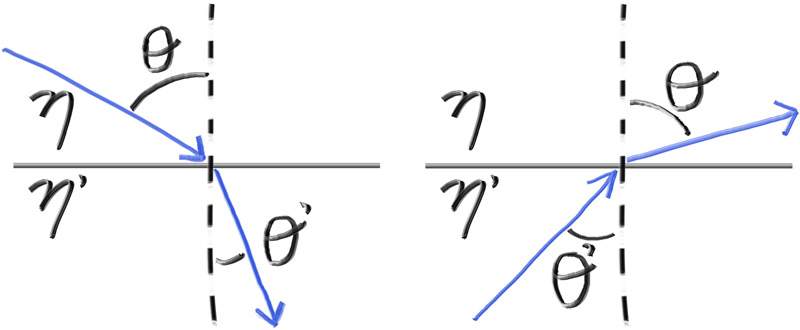

The refraction is described by Snell’s law:

$$ \eta \cdot \sin\theta = \eta' \cdot \sin\theta' $$

Where $\theta$ and $\theta'$ are the angles from the normal, and $\eta$ and $\eta'$ (pronounced "eta" and "eta prime") are the refractive indices (typically air = 1.0, glass = 1.3–1.7, diamond = 2.4). The geometry is:

In order to determine the direction of the refracted ray, we have to solve for $\sin\theta'$:

$$ \sin\theta' = \frac{\eta}{\eta'} \cdot \sin\theta $$

On the refracted side of the surface there is a refracted ray $\mathbf{R'}$ and a normal $\mathbf{n'}$, and there exists an angle, $\theta'$, between them. We can split $\mathbf{R'}$ into the parts of the ray that are perpendicular to $\mathbf{n'}$ and parallel to $\mathbf{n'}$:

$$ \mathbf{R'} = \mathbf{R'}{\bot} + \mathbf{R'} $$

If we solve for $\mathbf{R'}{\bot}$ and $\mathbf{R'}$ we get:

$$ \mathbf{R'}{\bot} = \frac{\eta}{\eta'} (\mathbf{R} + \cos\theta \mathbf{n}) $$ $$ \mathbf{R'} = -\sqrt{1 - |\mathbf{R'}_{\bot}|^2} \mathbf{n} $$

You can go ahead and prove this for yourself if you want, but we will treat it as fact and move on. The rest of the book will not require you to understand the proof.

We know the value of every term on the right-hand side except for $\cos\theta$. It is well known that the dot product of two vectors can be explained in terms of the cosine of the angle between them:

$$ \mathbf{a} \cdot \mathbf{b} = |\mathbf{a}| |\mathbf{b}| \cos\theta $$

If we restrict $\mathbf{a}$ and $\mathbf{b}$ to be unit vectors:

$$ \mathbf{a} \cdot \mathbf{b} = \cos\theta $$

We can now rewrite $\mathbf{R'}_{\bot}$ in terms of known quantities:

$$ \mathbf{R'}_{\bot} = \frac{\eta}{\eta'} (\mathbf{R} + (\mathbf{-R} \cdot \mathbf{n}) \mathbf{n}) $$

When we combine them back together, we can write a function to calculate $\mathbf{R'}$:

...

inline vec3 reflect(const vec3& v, const vec3& n) {

return v - 2*dot(v,n)*n;

}

inline vec3 refract(const vec3& uv, const vec3& n, double etai_over_etat) {

auto cos_theta = fmin(dot(-uv, n), 1.0);

vec3 r_out_perp = etai_over_etat * (uv + cos_theta*n);

vec3 r_out_parallel = -sqrt(fabs(1.0 - r_out_perp.length_squared())) * n;

return r_out_perp + r_out_parallel;

}

And the dielectric material that always refracts is:

...

class metal : public material {

...

};

class dielectric : public material {

public:

dielectric(double index_of_refraction) : ir(index_of_refraction) {}

bool scatter(const ray& r_in, const hit_record& rec, color& attenuation, ray& scattered)

const override {

attenuation = color(1.0, 1.0, 1.0);

double refraction_ratio = rec.front_face ? (1.0/ir) : ir;

vec3 unit_direction = unit_vector(r_in.direction());

vec3 refracted = refract(unit_direction, rec.normal, refraction_ratio);

scattered = ray(rec.p, refracted);

return true;

}

private:

double ir; // Index of Refraction

};

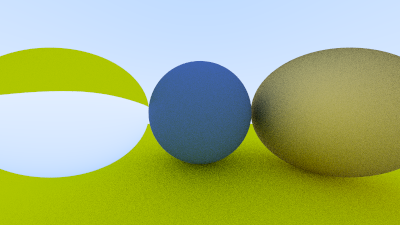

Now we'll update the scene to change the left and center spheres to glass:

auto material_ground = make_shared<lambertian>(color(0.8, 0.8, 0.0));

auto material_center = make_shared<dielectric>(1.5);

auto material_left = make_shared<dielectric>(1.5);

auto material_right = make_shared<metal>(color(0.8, 0.6, 0.2), 1.0);

This gives us the following result:

Total Internal Reflection

That definitely doesn't look right. One troublesome practical issue is that when the ray is in the material with the higher refractive index, there is no real solution to Snell’s law, and thus there is no refraction possible. If we refer back to Snell's law and the derivation of $\sin\theta'$:

$$ \sin\theta' = \frac{\eta}{\eta'} \cdot \sin\theta $$

If the ray is inside glass and outside is air ($\eta = 1.5$ and $\eta' = 1.0$):

$$ \sin\theta' = \frac{1.5}{1.0} \cdot \sin\theta $$

if (refraction_ratio * sin_theta > 1.0) {

// Must Reflect

...

} else {

// Can Refract

...

}

double cos_theta = fmin(dot(-unit_direction, rec.normal), 1.0);

double sin_theta = sqrt(1.0 - cos_theta*cos_theta);

if (refraction_ratio * sin_theta > 1.0) {

// Must Reflect

...

} else {

// Can Refract

...

}

class dielectric : public material {

public:

dielectric(double index_of_refraction) : ir(index_of_refraction) {}

bool scatter(const ray& r_in, const hit_record& rec, color& attenuation, ray& scattered)

const override {

attenuation = color(1.0, 1.0, 1.0);

double refraction_ratio = rec.front_face ? (1.0/ir) : ir;

vec3 unit_direction = unit_vector(r_in.direction());

double cos_theta = fmin(dot(-unit_direction, rec.normal), 1.0);

double sin_theta = sqrt(1.0 - cos_theta*cos_theta);

bool cannot_refract = refraction_ratio * sin_theta > 1.0;

vec3 direction;

if (cannot_refract)

direction = reflect(unit_direction, rec.normal);

else

direction = refract(unit_direction, rec.normal, refraction_ratio);

scattered = ray(rec.p, direction);

return true;

}

private:

double ir; // Index of Refraction

};

auto material_ground = make_shared<lambertian>(color(0.8, 0.8, 0.0));

auto material_center = make_shared<lambertian>(color(0.1, 0.2, 0.5));

auto material_left = make_shared<dielectric>(1.5);

auto material_right = make_shared<metal>(color(0.8, 0.6, 0.2), 0.0);

class dielectric : public material {

public:

dielectric(double index_of_refraction) : ir(index_of_refraction) {}

bool scatter(const ray& r_in, const hit_record& rec, color& attenuation, ray& scattered)

const override {

attenuation = color(1.0, 1.0, 1.0);

double refraction_ratio = rec.front_face ? (1.0/ir) : ir;

vec3 unit_direction = unit_vector(r_in.direction());

double cos_theta = fmin(dot(-unit_direction, rec.normal), 1.0);

double sin_theta = sqrt(1.0 - cos_theta*cos_theta);

bool cannot_refract = refraction_ratio * sin_theta > 1.0;

vec3 direction;

if (cannot_refract || reflectance(cos_theta, refraction_ratio) > random_double())

direction = reflect(unit_direction, rec.normal);

else

direction = refract(unit_direction, rec.normal, refraction_ratio);

scattered = ray(rec.p, direction);

return true;

}

private:

double ir; // Index of Refraction

static double reflectance(double cosine, double ref_idx) {

// Use Schlick's approximation for reflectance.

auto r0 = (1-ref_idx) / (1+ref_idx);

r0 = r0*r0;

return r0 + (1-r0)*pow((1 - cosine),5);

}

};

...

world.add(make_shared<sphere>(point3( 0.0, -100.5, -1.0), 100.0, material_ground));

world.add(make_shared<sphere>(point3( 0.0, 0.0, -1.0), 0.5, material_center));

world.add(make_shared<sphere>(point3(-1.0, 0.0, -1.0), 0.5, material_left));

world.add(make_shared<sphere>(point3(-1.0, 0.0, -1.0), -0.4, material_left));

world.add(make_shared<sphere>(point3( 1.0, 0.0, -1.0), 0.5, material_right));

...